Developing Positive Classroom Environments

Strategies for nurturing adolescent learning

Beth Saggers, Beth Saggers

- 346 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

Developing Positive Classroom Environments

Strategies for nurturing adolescent learning

Beth Saggers, Beth Saggers

Über dieses Buch

The middle years of learning are increasingly recognised as one of the most challenging yet opportune periods for growth and development. Based on the Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) framework, this book will equip educators with the appropriate knowledge, skills and strategies to support learners in maximising their educational success, managing emotional issues and making a successful transition to adulthood. Part A outlines the principles of the PBS framework, defines key characteristics of middle-years learners and provides insight from neuroscience into the nature of the adolescent brain. This section also looks at the importance of listening to the student voice, highlights issues that can arise during the transition into the middle years of schooling, and discusses the use of evidence-based PBS practices to encourage engagement and establish clear behavioural expectations with learners. Part B focuses on the practical aspects of implementing universal PBS strategies in the classroom, including developing strong and effective relationships with students, promoting school connectedness and supporting self-regulation. Part C examines more focused and intensive interventions, and provides strategies for working with students experiencing stress, anxiety and bullying. Finally, Part D discusses ways to support a range of perspectives and experiences in the middle-years, including trauma-affected students, ethnic and cultural diversity and students on the autism spectrum, as well as ways to use ICT to re-engage vulnerable students. This is an essential reference for both primary and secondary educators, revealing how PBS strategies can play a profound role in positively transforming classroom behaviour.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Information

Part B

Tier 1—Universal interventions

Chapter 7

Tier 1

- the influences on teachers’ discipline practices

- the impact of fluctuating energy levels on classroom learning and behaviour

- strategies to identify and manage the energy fluctuations of students

- strategies to address low and mid-level behavioural disruption.

- a sense of personal worth—an awareness of their own level of skill and potential that contributes to their personal development and social connection

- an internal locus of control—the ability to consider the effects of their behaviour on others and moderate that behaviour according to the situation

- a sense of being valued, safe and secure—understanding the conditions and knowing the people to whom they can turn when faced with unsettling or frightening situations

- appropriate social behaviour and conflict-resolution skills—identifying and displaying behaviours that peacefully resolve conflict and maintain connections with peers and other community members.

What influences our discipline practices?

- our beliefs about children and childhood at different ages and our views on children’s capacity to self-manage their behaviour

- our views of disruption as either an error of skill or a deliberate act of defiance

- our own formal education experiences

- our understanding of the key theories of discipline and teaching

- our values, which govern which behaviours we see as problematic.

- The disruption will be brought under control, quickly and safely.

- The disruption should be less likely to recur.

- Positive learning intentions are communicated.

- There are no unintended side effects on the child.

- Other children will feel safe about how they would be treated if in the same situation.

- Your overall classroom environment (e.g., organised, chaotic, boring, messy, safe, fun)

- You, their teacher (e.g., warm, tough, encouraging, nasty, someone who presents great lessons)

- The learning experiences (e.g., inspiring, interesting, challenging)

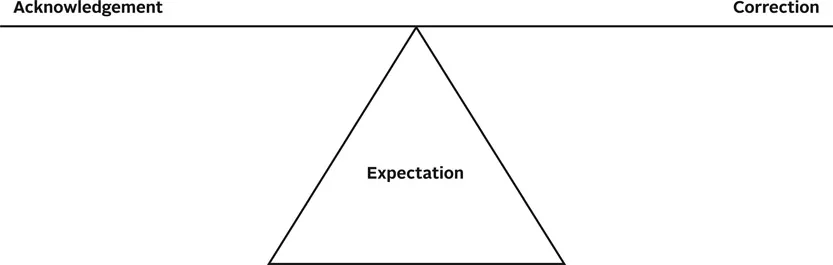

Perceptions of behaviour