![]()

1 The Labour Party and the Electorate

Ivor Crewe

Those are not the policies with which to win the next general election. The Labour Party needs a socialist policy, and not the tired worn-out social democratic policy that led to our defeat in 1979.

(Arthur Scargill on James Callaghan’s speech to the TUC, as reported in The Times, 3 September 1980)

Some Yorkshire miners are ignoring their union’s policy and paying £150 for hernia operations at a private clinic. They are paying for private medicine rather than wait for two years for the operation on the National Health Service.

An official of the National Union of Mineworkers at Barnsley said: ‘It does not surprise me. While the union’s stand would be against private medicine, obviously our members are free to choose. A man earning top money in the pits would regard the £150 as a drop in the ocean if it meant he could get back to work quickly and not lose pay.’

(‘Yorkshire miners choose private clinic’, The Times, 6 September 1980)

Exactly twenty years ago, in the aftermath of Labour’s decisive defeat at the 1959 general election – its third in succession – Mark Abrams, Richard Rose and Rita Hinden wrote a lengthy post-mortem called Must Labour Lose?1 The answer they gave was: probably. Their pessimism was founded on three interconnected arguments. First, the sheer size of the working-class base on which Labour had traditionally relied was gradually contracting. Labour-intensive heavy industry was in decline; capital-intensive light industry and the service sector were expanding. More and more voters were changing their boiler suits for white collars. Secondly, working-class standards of living had markedly improved: a decade of economic growth, full employment, slum clearance, widening educational opportunities and mass production of cheap consumer durables (especially cars and televisions) had left its mark. With middle-class standards of living, it was inferred, went middle-class values – and voting patterns. Thirdly, as a result, Labour’s traditional ‘cloth-cap’ image and policies, notably public ownership, were losing appeal. The only way to avoid yet another election defeat was to catch up with the times and become a cross-class party committed to maintaining, rather than abolishing, the mixed economy that had worked so well in the 1950s.

It is tempting to dismiss the book as a historical memento. Academic research has since provided strong evidence that a rise in working-class living standards does not necessarily lead to Conservative voting.2 And anyway, the affluence of the 1950s gave way to the stagnation of the 1960s and the apparent decline of the 1970s. More compelling still, in the two decades that have elapsed since the book’s publication Labour has won four of the six general elections and occupied office for longer than the Conservatives. Yet Labour’s defeat in May 1979 prompts a return to the issues raised twenty years earlier. This is not simply because the defeat was a serious one – more so than is usually realised – but for two additional reasons. First, the cause of Labour’s downfall was close to that predicted by Abrams and his colleagues: the party’s desertion by working-class voters out of sympathy with its policies. And secondly, the 1979 election, far from being yet another swing of the electoral pendulum, marked a further stage in what has turned out to be, despite the four election ‘victories’ under Harold Wilson, a long-term erosion of support. It is right that one should once again ask: must Labour lose?

The last general election marked the most emphatic rejection of the Labour Party for almost half a century. Not since its débâcle of 1931 had Labour suffered such an adverse swing or seen its share of the vote (at 36.9 per cent) or of the electorate as a whole (at 28.0 per cent) fall so low. Only the malapportionment of constituency electorates and the below-average swing in Labour marginals prevented a Conservative parliamentary landslide of 1959 proportions. As it was, Labour was virtually wiped out as a parliamentary force in the south (outside London) and in rural and small-town Britain (outside mining areas).

The Labour Party also took a severe knock as the parliamentary representative of the working class. The consistent findings of three separate large-scale surveys3 leave little doubt that the heaviest desertion from Labour occurred among manual rather than non-manual workers, especially among the younger generation and skilled workers. (This was reflected in the above-average and sometimes unprecedented anti-Labour swings in such high-wage working-class areas as the new towns, the Lancashire and Yorkshire coalfields and the car-worker suburbs.) The large majority of Labour voters were, as in all elections, manual workers; but by 1979 this ceased to be true. The large majority of manual workers (63 per cent) did not turn out to vote Labour; indeed, even among manual workers who voted, the majority of their ballots (52 per cent) were cast for non-Labour candidates. From this perspective Labour had moved some distance from being the party, as opposed to a party, of the working class.

Although this chapter’s focus will be the last two decades, it is worth dwelling initially on the main reasons for Labour’s defeat in 1979. Here I must summarise drastically the results of detailed analyses to be published elsewhere.4 First, Labour did not lose because of such ‘undemocratic’ factors as inferior organisation, poorer funding, or defective public relations. The survey evidence shows that the coverage and impact of convassers, advertising and television broadcasts gave only a trace of an advantage to the Conservatives. (The effect of the press is, of course, another matter; but to attribute to it major responsibility for Labour’s defeat one would have to show that the press was significantly more anti-Labour in 1979 than in 1974.) And it did not lose through the relative appeal of the party leaders: the polls consistently showed Mr Callaghan to be more popular than Mrs Thatcher, and to be drawing further ahead as the campaign progressed. Nor did Labour lose as a result of last-minute incidents: there was nothing comparable to the Enoch Powell speeches or embarrassing statistics of the 1970 and February 1974 campaigns. On the contrary, the 1979 election was unusual for its sober uneventfulness, and for the clarity of choice offered to voters. Labour lost, in fact, for the most obvious and proper of reasons: partly on its record, but mainly on the policies and objectives of the Conservative Party.

Secondly, as already mentioned, Labour lost through the desertion of its working-class supporters: the swing was 10–11 per cent among skilled workers, and as high as 16 per cent among younger working-class men. These deserters did not stay at home, moreover, but in the main switched right over to the Conservatives. A replication for October 1974 to 1979 of the kind of calibrated vote-turnover table that was a feature of Political Change in Britain5 shows that ‘differential abstention’ had a negligible impact. The main components of the anti-Labour swing were, in order of importance, straight conversion from Labour to Conservative, and movement to and from the Liberals (especially October 1974 Liberals reverting to their original Conservative loyalties). Thus the best summary answer to the question ‘Why did Labour lose, and lose so badly?’ would be: because, after a long and serious campaign, large sectors of the working class regarded Conservative policies and objectives as being more in line with their own interests and values.

One should be wary, of course, of exaggerating the significance of a single election result, however dramatic. Strictly temporary factors such as the preceding winter’s strikes and the inevitable disillusion with an outgoing government explain part of the result. After all, at the previous election Conservative support had dipped to its lowest level since 1906 and to third place among young voters and in Scotland; yet the doleful prognostications of the time turned out largely to be unfounded. None the less, for reasons this chapter will reveal, the two cases are not exactly parallel. As I have argued elsewhere,6 the Conservatives’ low stock in 1974 could be attributed to the combination of an increasingly fickle electorate and short-term forces alone. But the placing of the 1979 results in a long-term and comparative context does suggest a more enduring basis to Labour’s electoral decline.

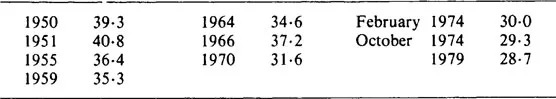

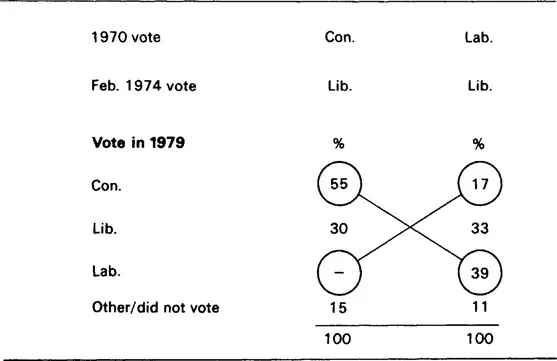

This can be illustrated in various ways. First, as Table 1.1 shows, 1979 marks a further stage in what transpires to be a quarter-century’s almost unremitting erosion of Labour support. At every election since 1951, with only one exception (1966), an additional slice of the electorate has stopped voting Labour; added together the slices amount to a loss of almost a third of Labour’s support between 1951 and 1979. It is easy to forget that in 1964 Harold Wilson rode to power on a smaller share of the electorate than Hugh Gaitskell obtained five years earlier; and that although Labour twice won office (just) in 1974 it did so by electoral default. Labour’s loss of votes in February 1974 was, I believe, particularly significant, for at the time Labour was not simply out of office but in opposition to an unpopular and unsuccessful government which was attacking the prerogatives of Labour’s traditional constituencies – trade unionists and council house tenants. Analysis of the four-election vote flow from 1970 to 1979 shows that, in contrast to the Conservatives, Labour has so far failed to recapture more than a minority of its 1974 deserters to the Liberals (see Table 1.2).

Table 1.1 Labour’s Share of the Great Britain Electorate, 1950–79

Table 1.2 The 1979 Vote of Major Party Defectors to the Liberals between 1970 and February 1974

Secondly, Labour’s falling vote has occurred despite earlier predictions that time and demography were on its side. In the late 1960s Butler and Stokes suggested, albeit tentatively, that Labour would become the net beneficiary of three demographic processes: (1) the dying out of those who had first entered the electorate before 1918 and thus had been socialised into partisanship before Labour became a serious contender for power; (2) narrowing class differences in longevity; (3) the greater fertility of manual than non-manual women (combined with the fact that party allegiance tends to be bequeathed from parents to children). All three of these demographic processes have occurred (although class differences in fertility are narrower than originally envisaged), yet Labour’s share of the vote was lower in 1979 than exactly fifty years earlier. One might also have expected Labour to profit from the neardisappearance of two purported sources of Conservative support in the 1950s and early 1960s: social deference and ‘affluence’ – the common experience and expectation of constantly rising living standards.

Thirdly, electoral decline for the moderate left on this scale is unique to Britain. Among European countries since the war not even the faltering position of the Danish Social Democrats bears any resemblance to it. It is true that, with the exception of the German SDP, social democratic parties have been in retreat throughout the West in the 1970s. However, by the late 1970s there were only three European democracies – Belgium, Eire and Switzerland – with a smaller ‘combined-lef’ vote (S...