eBook - ePub

Functional Structure(s), Form and Interpretation

Perspectives from East Asian Languages

Andrew Simpson, Audrey-Li Yen-hui, Andrew Simpson, Audrey-Li Yen-hui

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 296 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Functional Structure(s), Form and Interpretation

Perspectives from East Asian Languages

Andrew Simpson, Audrey-Li Yen-hui, Andrew Simpson, Audrey-Li Yen-hui

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

The issue of how interpretation results from the form and type of syntactic structures present in language is one which is central and hotly debated in both theoretical and descriptive linguistics.

This volume brings together a series of eleven new cutting-edge essays by leading experts in East Asian languages which shows how the study of formal structures and functional morphemes in Chinese, Japanese and Korean adds much to our general understanding of the close connections between form and interpretation. This specially commissioned collection will be of interest to linguists of all backgrounds working in the general area of syntax and language change, as well as those with a special interest in Chinese, Japanese and Korean.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Functional Structure(s), Form and Interpretation als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Functional Structure(s), Form and Interpretation von Andrew Simpson, Audrey-Li Yen-hui, Andrew Simpson, Audrey-Li Yen-hui im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Languages & Linguistics & Languages. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Part I

FUNCTIONAL STRUCTURE AND PROCESSES OF INTERPRETATION IN THE DP/NP

1

NP AS ARGUMENT

Yen-hui Audrey Li and Yuzhi Shi

1. Introduction

The articulation of X’-theory, extending it to functional categories, has led to the revision of projections for nominal expressions: an argument nominal phrase does not have the straightforward structure [NP. . . .N. . .] with N(oun) heading a projection Noun Phrase (NP). Rather, it has a functional head, Determiner (D), which takes a complement NP and projects to a Determiner Phrase (DP) (see Szabolsci, 1983/84, Abney 1987, for instance).1 NPs and DPs are two distinct categories: a DP generally is an argument and an NP, a predicate. D has the function of making a predicate into an argument (Chierchia 1998). Alternatively, an NP is a restriction for D to range over.2 D is an operator ranging over a restriction or binding a variable in N (Longobardi, 1994, 633–334).

In languages requiring an article (a determiner) to occur with a noun, such as English, there is clear support for the existence of a DP/NP distinction. After all, one can hear an article with a noun in certain contexts and not in others. However, in languages that do not require an article, such as Chinese, there is no immediate support for adopting a DP/NP distinction. The same form, an NP without an article, occurs in both argument and predicative positions. Naturally, the following question arises: is distinguishing DPs from NPs necessary in such a language? Two approaches have been pursued. One is to maintain a one-to-one matching relation between form and meaning and claim that all languages have the same DP/NP distinction (see a recent representative work, Borer 2000). The other is to make syntactic structures reflect morphology more closely: if a language does not require a determiner to make an argument, a DP is not projected and an argument is still represented as an NP. Proper interpretations are obtained by a semantic ‘type-shifting’ rule which type-shifts an NP from a predicate to an argument (see Chierchia 1998). According to these approaches, then, an argument is either always projected as a DP or is projected as an NP which must undergo a semantic type-shifting rule.

Logically, however, an NP should be able to occur in an argument position without the application of a type-shifting rule, as long as it can be properly interpreted (or bound by an operator, see the paragraphs above).3 Recall that a D serves to make an argument the nominal expression containing an NP. A D is an operator binding a variable in an NP, i.e, an NP provides a restriction (variable) for an operator in D. Suppose a language can generate an operator away from its restriction, i.e., not within the same nominal expression, while an operator-variable relation still holds, then an NP can occupy an argument position and still be properly interpreted without undergoing a semantic type-shifting rule. More concretely, let us consider the morphological composition of wh-words in various languages. In the works of Watanabe (1992), Cheng (1991), Aoun and Li (1993a, b), Tsai (1994), among others, some versions of the following idea have been put forward: languages may differ in the composition of their wh-phrases. Three different types of languages have been identified. One type is represented by English. In this language, a wh-word consists of a quantification and a restriction. The two parts function as a unit; i.e., they undergo syntactic processes such as movement as a unit. Japanese represents another type, whose wh-phrases also consist of a quantification and a restriction but the quantification part can be moved away from the restriction part. The third type is represented by Chinese, whose wh-words are only a restriction, bound by an operator outside the wh-expressions. The different behavior of these three types of wh-words are reflected in the formation of wh-interrogatives and the formation of noninterrogative universal and existential quantificational expressions. Regarding the formation of wh-interrogatives, which involves movement of a wh-quantifier to the peripheral position of the interrogative clause, this proposal accounts for the following facts, focusing on the comparison between English and Chinese:4

- (1) a. English moves wh-words to form wh-interrogatives because wh-words are quantificational.

b. Chinese generates an operator (quantification) and a restriction in separate projections. The restriction is the wh-word and the quantification is a question operator generated in a question projection or in (Spec of) Comp (cf. Aoun and Li 1993a).

Because a wh-word in Chinese is only a restriction, it is not surprising that it does not have independent quantificational force and obtains a quantificational interpretation via a quantificational element in the context. For instance, it can be interpreted as a universal quantifier when licensed by the universal quantifier dou, as in (2a); it can be interpreted as an existential quantifier when licensed by an existential quantifier as in a conditional clause (2b); and it can be interpreted as an interrogative in the context of a wh-question (suggested by the optional root-clause particle ne), (2c).

- (2) a. shenme dou hao.

what all good

‘Everything is good.’

b. ruguo ni xihuan shenme, wo jiu ba ta mai-xia-lai.

if you like what I then Ba it buy-down

‘If you like something, I will buy it.’ - c. ta yao shenme (ne)?

he want what Question

‘What does he want?’

In contrast, a wh-word in English is quantificational. It has a fixed interpretation and does not have the range of interpretations illustrated in (2a-b).

Nonetheless, wh-words in Chinese share with those in English the possibility to properly bind or control another anaphor, bound pronoun or PRO, i.e., they both behave like arguments:

- (3) a. Whoi believes himselfi to be the best?

b. Whoi wants [PROi to speak out]?

- (4) a. sheii dou bu gan ba zijii/tai de yisi shuo chulai.

who all not dare BA self/he De intention speak out

‘Nobody dares to speak out self ’s/his intention.’

b. sheii dou xiang [PROi qu].

who all want go

‘Everyone wants to go.’

In other words, Chinese, in contrast to English, illustrates a case where a restriction alone is generated in an argument position and functions like an argument.

If such an approach to cross-linguistic variations on the formation of questions and on the behavior of quantificational expressions based on variations in morphological compositions is correct, we expect to find more instances demonstrating that Chinese generates only a restriction in the place where English generates a quantification and a restriction as a unit. That is, following the semantic distinction between D and N, we expect to find instances where an NP in Chinese is generated in the positions where a DP is generated in English and both still function alike – as an argument.

We show in this work that NPs in Chinese indeed are allowed in argument positions and behave like arguments. There are interesting generalizations in this language suggesting that NPs are generated in argument positions, licensed by and interpreted with an operator outside the nominal expression. Such generalizations indicate that a semantic type-shifting rule to shift an NP-predicate to an argument need not apply in relevant Chinese cases, contrary to what Chierchia (1998) proposes. Moreover, these generalizations demonstrate that a null D and a DP are not always projected when a determiner does not occur overtly.5 Empirical supports for such generalizations come from the study on the plural/collective morpheme -men and the derivation of relative constructions in Chinese.

2. The plural/collective morpheme -men6

The first case in support of our claims involves generalizations concerning the plural/collective morpheme -men in Chinese. In order to account for the distribution of -men and its interaction with other constituents within a nominal expression, Li (1999a) suggests that the plural/collective marker -men represents a plural feature in the head position of a Number projection. This plural feature can be realized on an element that has undergone movement through an empty Classifier to D, movement being governed by the Head Movement Constraint which essentially disallows a Head to move across another Head (Travis 1984). We elaborate on this proposal in the following paragraphs.

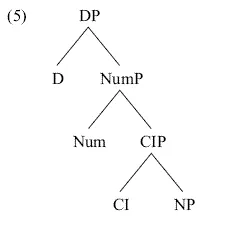

Based on the distribution and ordering of the constituents within a nominal expression, Li (1998, 1999a, b) argues that a full nominal phrase in Chinese has the following structure (see Tang 1990):

A noun is generated in N; a classifier in Cl; the plural/collective in Num and a demonstrative or proper name or pronoun in D. If Classifier is not filled lexically (i.e., if a classifier lexical item is not present), an N can be raised to Num, combined with the plural/collective feature, realized as -men, and then, raised to D to check a [+definite] feature in D. This derives a well-formed [N-men].

(6) laoshi dui xuesheng-men hen hao.

teacher to student-MEN very good

‘The teacher is nice to the students.’

teacher to student-MEN very good

‘The teacher is nice to the students.’

If Classifier is filled lexically (a classifier is present), an N cannot be raised and combined with -men in Num (the Head Movement Constraint), which accounts for the unacceptability of nominal expressions with the form *[(D+) Num + Cl + N-men]

(7) *laoshi dui (zhe/na) san-ge xuesheng-men tebie hao.

teacher to these/those three-Cl student-MEN especially good

‘The teacher is especially nice to (these/those) three students.’

teacher to these/those three-Cl student-MEN especially good

‘The teacher is especially nice to (these/those) three students.’

An N can also just move up to Number when Classifier is empty and D is lexically filled (by a demonstrative, for instance). This captures the contrast in acceptability between [D + N-men] and *[D + Num + Cl + N-men] expressions:

- (8) a. laoshi dui zhe/na-xie7 xuesheng-men tebie hao.

teacher to these/those student-MEN especially good

‘The teacher is especially nice to these/those students.’

b. *laoshi dui zhe/na ji-ge xuesheng-men tebie hao.8

teacher to these/those several-Cl student-MEN especially good

‘The teacher is especially n...