eBook - ePub

Viral Ecology

Christon J. Hurst, Christon J. Hurst

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 639 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Viral Ecology

Christon J. Hurst, Christon J. Hurst

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Viral Ecology defines and explains the ecology of viruses by examining their interactions with their hosting species, including the types of transmission cycles that have evolved, encompassing principal and alternate hosts, vehicles, and vectors. It examines virology from an organismal biology approach, focusing on the concept that viral infections represent areas of overlap in the ecology of viruses, their hosts, and their vectors.

- The relationship between viruses and their hosting species

- The concept that viral interactions with their hosts represents a highly evolved aspect of organismal biology

- The types of transmission cycles which exist for viruses, including their hosts, vectors, and vehicles

- The concept that viral infections represent areas of overlap in the ecology of the viruses, their hosts, and their vectors

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Viral Ecology als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Viral Ecology von Christon J. Hurst, Christon J. Hurst im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Biological Sciences & Microbiology. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Thema

Biological SciencesThema

MicrobiologySection IV

Viruses of Macroscopic Animals

10

Ecology of Insect Viruses

LORNE D. ROTHMAN* and JUDITH H. MYERS†, *SAS Institute (Canada) Inc., Toronto, Ontario M5J 2T3, Canada; †Centre for Biodiversity Research, Departments of Zoology and Plant Science, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z4, Canada

I. Introduction

II. Types of Viruses

III. Transmission

A. Horizontal Transmission

B. Vertical Transmission

C. Latent Virus

IV. Viruses and the Host Individual

A. Virulence

B. Debilitating Effects on Survivors

V. Viruses and the Host Population

A. General Theory

B. Mathematical Models

C. Experiments

D. Biological Control

VI. Synthesis: Evolution of Pathogen–Host Associations

References

I. INTRODUCTION

Insects, mostly in the orders Diptera (flies), Hymenoptera (e.g., sawflies, wasps, bees), Coleoptera (beetles), and particularly Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) are hosts to a variety of viruses. Research on insect viruses has focused on the more virulent pathogens of pests of forests and agriculture. However, the effects of viruses are extremely varied. Some cause spectacular epizootics and extensive mortality, while others are more benign and cause less obvious characteristics of disease. Recent advances in molecular biology have greatly improved our ability to identify and describe insect viruses and to study their behavior within the host. But to predict viral epizootics, or to successfully use virus to control pest species, we require a greater understanding of viral ecology. We do not provide an exhaustive review of insect host–virus interactions. Rather, we focus on some of the fundamental aspects of transmission, and effects of viruses on individuals and on host populations.

II. TYPES OF VIRUSES

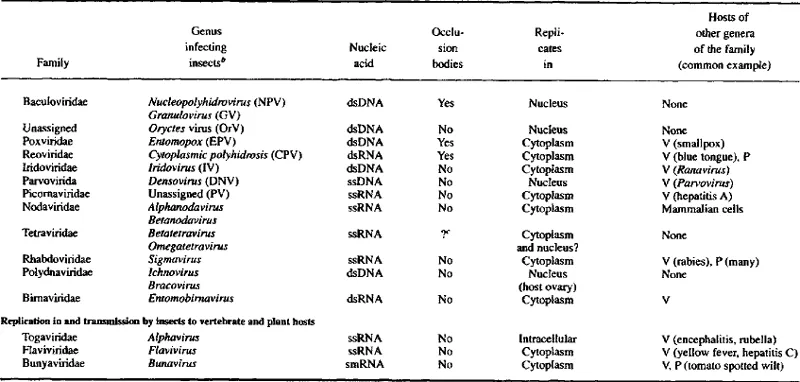

We outline in Table I the major categories of insect viruses. Insect viruses can be categorized as being occluded or nonoccluded, of being DNA or RNA viruses, and of replicating in the nucleus or cytoplasm of cells. Except for the Baculoviridae and the Nudaurelia β virus group, families including entomoviruses also have forms that infect vertebrates or plants. The baculoviruses are specific to insects and have been the focus of the most study (Cory et al., 1997). Two major groups of baculoviruses are the nuclear polyhedral viruses (NPVs) and granulosis viruses (GVs), DNA viruses that replicate in the nuclei of cells. The virions of baculoviruses are encapsulated in protein occlusion bodies (OBs), which can be observed with a light microscope: 1–4 μm for NPVs and 0.1–0.5 μm for GVs. The protein matrix of the OBs protects the virions in the environment following the death of infected individuals.

TABLE I

Families and Genera of Viruses Associated with Insects Either as Pathogens or as Viruses that Replicate within the Insect and Are Transmitted to Vertebrate (V) or Plant Hostsa

aBased on ICTV (1995).

bAbbreviations of genera are in parentheses.

cMay sometimes be incorporated in occlusion bodies of baculoviruses (Moore, 1991).

III. TRANSMISSION

Two general pathways of virus transmission are horizontal, among individuals in the same generation, and between generations through environmental contamination, and vertical, directly from parents to offspring (Andreadis, 1987; Kukan, 1996).

A. Horizontal Transmission

Virulent pathogens such as nuclear polyhidrosis viruses (NPVs) and granulosis viruses (GVs) of Lepidoptera are primarily transmitted both within and between host generations through the release of OBs into the environment following death of infected individuals (Myers, 1993). Low levels of infectious virus can also be released in feces and regurgitate from the midgut in the late stages of infections (Vasconcelos, 1996). Less lethal pathogens are transmitted primarily in feces and regurgitate. This mode of transmission is important in Oryctes virus, cytoplasmic polyhidrosis viruses (CPVs), and entomopox viruses (EPVs) of some Lepidoptera, NPVs of sawflies, and small RNA viruses infecting bees (Sikorowski et al., 1973; Granados, 1981; Kelly, 1981; Payne, 1981, 1982; Zelazny and Alfiler, 1991; Myers and Rothman, 1995a). Oryctes virus is excreted by infected adult coconut palm rhinoceros beetles, Oryctes rhinoceros at breeding sites (coconut trunks) and while mating (Zelazny 1973, 1976; Zelazny and Alfiler, 1991; Zelazny et al., 1992; Kelly, 1981). The small RNA viruses, like the picornaviruses and sacbrood virus, cause chronic and acute honey bee paralysis. These viruses are likely secreted from salivary and hypopharyngeal glands into the liquid added by bees to the pollen as they collect it (Bailey, 1973; Kelly, 1981). In this way they are transmitted to other individuals. Although horizontal transmission usually occurs by ingestion of contaminated food such as foliage or egg chorion on hatching (discussed in what follows), iridescent viruses (IVs) of Aedes taeniarhynchus and Tipula oleracea (Diptera) (Linley and Nielson, 1968b; Carter, 1973a,b), and an NPV of Heliothis armigera (Dhandapani et al., 1993a) can be transmitted by cannibalism.

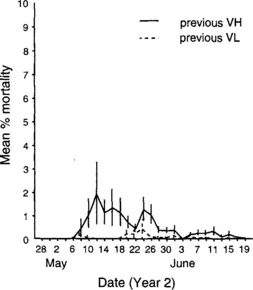

An example of host mortality following horizontal transmission of an NPV is illustrated in Figure 1. In this experiment, young tent caterpillars were fed leaves contaminated with NPV in the laboratory and then introduced to host colonies at two densities in the field. The first peak in mortality involves the lab-infected individuals that released NPV occlusion bodies when they died. Susceptible individuals ingested contaminated foliage and died about 2 weeks later, causing the second peak in mortality. Bi- and trimodal peaks of host mortality have been recorded for Pieris brassicae following experimental introduction of GV (Hochburg, 1991a) and for field populations of gypsy moth (Woods and Elkinton, 1987).

Fig. 1 Mean percentage mortality (+S.E.) of Malacosoma californicum pluviale (Lepidoptera) larvae from NPV observed at 2-day intervals in the year of introduction of NPV and host colonies at high (VH) and low (VL) larval and viral densities. Adapted with permission from Rothman (1997).

1. Persistence

Persistence of active virus in the environment or in the host population is important to the dynamics of within- and between-generation infection. Viruses in occlusion bodies are likely to persist longer than nonoccluded viruses. However, a nonoccluded small RNA virus of aphids was found to persist and be transmitted through plants (Gildow and D’Arcy, 1988). This interaction is more likely for sucking than chewing insects, but it suggests that more than plant surfaces may be involved in the persistence of insect viruses.

Foliage is an important substrate for short-term persistence of viruses. For example, Pringle and Lewis (1997) found that NPV of the celery looper Anagrapha falcifera was still 80% active after 9 days when sprayed onto silk of sweet corn. However, virus on foliage is generally deactivated in a matter of hours to days through exposure to ultraviolet sunlight (David et al., 1968; Jaques, 1972; Ignoffo et al., 1977; see Benz [1987] and Cory et al. (1997) for reviews). Roland and Kaupp (1995) and Rothman and Roland (1998) found reduced infection by NPV of the forest tent caterpillar Malacosoma disstria in forest-edge habitats compared to that in forest-interior habitats, which they attributed to faster deactivation by sunlight.

Many of the most lethal insect viruses produce infective stages that can persist outside the host for one or many seasons in the soil (see Benz, 1987; Entwistle and Evans, 1985; Cory et al., 1997), on tree bark, or on host eggs. In agricultural and pasture habitats, where hosts and host food plants are in close proximity, soil may be an important source of inoculum for host infections for NPVs, GVs, and EPVs (Hurpin and Robert, 1972; Jaques, 1975; Crawford and Kalmakoff, 1977). In forest systems, the mechanisms by which virus is transferred from soil to caterpillars are unclear, but wind, rain splash, and contamination of hosts, predators, and parasitoids are possible (Entwistle and Evans, 1985; Olofsson, 1988).

Host food plants are also important substrates for transgeneration virus transmission, particularly in forest systems. Woods et al. (1989) released neonate larvae of the gypsy moth Lymantria dispar (Lepidoptera) onto sterilized, untreated,...