![]()

CHAPTER 1

Whisky's Historical Development

Early works on alchemy contain detailed descriptions of distilling and many illustrations of stills at work. This chapter describes how alchemy is at the heart of distillation and modern chemistry, then looks at how different countries developed their own spirits, e.g. Ireland, Canada and the USA and Japan, (Scotland being dealt with later in the book) and finally details literature works on distilling. The history of Irish distilling is a long, tangled and unfortunate one, however with a happy conclusion. Most histories of whisky place its first arrival in Europe in Ireland and then Scotland, with Irish Christian monks having obtained the secrets of distilling from the Moors in Spain, which they then brought home. Today, some 20 distilleries are currently operating on the island of Ireland and it is in a good place.

1.1 ALCHEMY AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN CHEMISTRY

“There is a glut of chemical books, but a scarcity of chemical truths.”

John French's preface to his Art of Distillation (1651)

It might, perhaps, be more comfortable for the grand narrative of modern science if alchemy – one of the pillars on which distilling is founded – could be quietly ignored or indeed forgotten entirely. The rational mind denies the contribution of mediaeval mystics and the arcane lore of the alchemist, yet both Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton pursued alchemical studies – Newton for more than 25 years, with alchemy central to his religious beliefs.

Early works on alchemy contain detailed descriptions of distilling and many illustrations of stills at work. It must be appreciated that these are, at heart, scientific works and that practitioners saw themselves as seekers after the truth, albeit proceeding from an Aristotelian view of a world comprised of four elements: earth, air, fire and water. Distillation represented the route to a ‘fifth essence’ or a kind of ultra-purified elixir that, in its highest form, could even prolong life. This was the search for the Philosopher's Stone that so engaged the mediaeval mind and, from the standpoint of the Aristotelian view, represented an entirely logical pursuit.

Even today, an echo may be found in writing about distilling. Primo Levi, chemist, writes1 in The Periodic Table:† “Distilling is beautiful. First of all, because it is a slow, philosophic, and silent occupation, which keeps you busy but gives you time to think of other things, somewhat like riding a bike. Then, because it involves a metamorphosis from liquid to vapour (invisible), and from this once again to liquid; but in this double journey, up and down, purity is attained, an ambiguous and fascinating condition, which starts with chemistry and goes very far. And finally, when you set about distilling, you acquire the consciousness of repeating a ritual consecrated by the centuries, almost a religious act, in which from imperfect material you obtain the essence, the spirit, and in the first place alcohol, which gladdens the spirit and warms the heart.”

The deliberate ambiguity of this passage, its overt reference to religion and its almost mystical tone – understandable, since Levi's skill as a chemist saved him from the forced labour gangs of Auschwitz – would, I suggest, be immediately familiar to the alchemist, despite proceeding from the formality and rigorous training of a modern scientist.

The inter-mingling of mystical symbolism, scientific practice and religious belief, so impenetrable to our contemporary mind-set with its emphasis on the rational and the material, leads us naturally to the monastery and the work of Franciscan friars, such as John of Rupescissa, Raymond Lull and the 13th century English philosopher and teacher Roger Bacon who, in 1267, attempted a synthesis of Aristotle's philosophy and science with contemporary theology, which he presented to his patron Pope Clement IV.

Basing much of their initial thinking and work on the Arabic writings of one Jabir ibn Hayyan (in Latin, Geber), who considered distillation the best way to separate nature into its component parts, they came to believe that the search for the fifth essence or ‘water of life’ would be through a series of distillations, often beginning with wine as the base. Silver and gold were also seen as incorruptible and therefore a suitable starting point for further transmutation. From this evolved the quest to change base metals into gold, the basis of much of the image of the alchemist and his search for the Philosopher's Stone in the popular imagination. However, as it is the medical application of distilling that led to distilled spirits as a beverage, the search for gold, however fascinating, is something of a sidebar to our story.

Perhaps the most famous description of distillation is given by Hieronymus Brunschwig. 2 “Distilling is nothing other than purifying the gross from the subtle and the subtle from the gross…and the subtle spirit made more subtle so that it can better pierce and pass through the body…conveyed to the place most needful of health and comfort.”

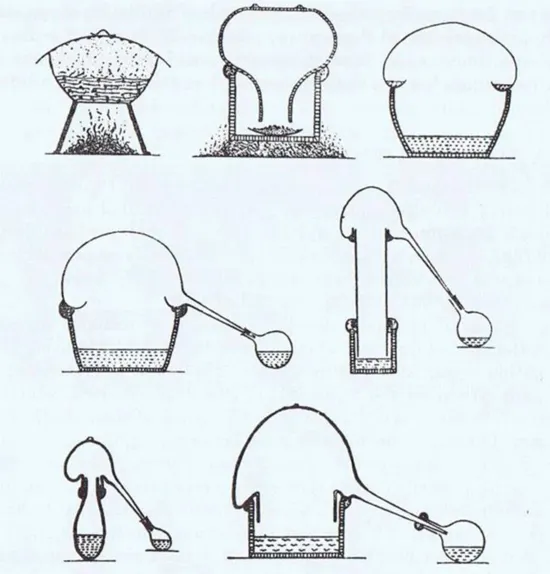

The constant process of purification, as seen below in John French's series of linked alembics (Figure 1.1), was of critical importance to the alchemist (and it might be noted that this continues to be so to today's pharmacist or even distiller of vodka), and illustrations frequently show the ‘pelican’, a device for ensuring reflux and rectification. The pelican also carries symbolic meaning, referring to the legend that, in time of famine, the mother pelican would wound herself by striking her breast with her beak to feed her young with her blood to prevent starvation. By extension, early Christians adapted the pelican to symbolize Jesus as the Redeemer. The red blood of the pelican was also suggestive of a distillation process that had achieved the formation of the ‘Red Tincture’ and was close to reaching its ultimate stage of final transmutation (symbolized by the rebirth of the phoenix from the fire of distillation).

Figure 1.1 Apparatus for redistillation from John French's Art of Distillation (1651).

Thus, it is no coincidence that the first written reference to whisky in Scotland (from the Exchequer Rolls of 1494, discussed further in Chapter 2) directs us to the monastery at Lindores Abbey or that, in 1510, Dom Bernado Vincelli first prepared the liqueur that today we know as Bénédictine in the Abbey of Fécamp in Normandy. To this day, the bottle also features the Latin motto of the Bénédictine order “Deo Optimo Maximo” meaning “to God, the good, the great”, as well as the coat of arms of Fécamp Abbey. Its counterpart, Chartreuse, dates originally from 1605 though it was not until 1737 that the liqueur was released to the world in a form resembling today's version.

While those traditions continue, until recently little remained of Lindores until the 2017 opening of a privately-funded distillery and visitor centre. Excavations at Pontefract and Selborne Priories have revealed fragments of 15th century alembics. These were made of glass or pottery, and thus intrinsically fragile, or possibly of pewter, which would have been re-used in another vessel once redundant for distilling. Very little thus survives of this early technology but based on the Pontefract and Selborne excavations and earlier work, archaeologists have suggested the conjectural evolution of the still (see Figure 1.2). As noted by Greenaway: 3 “medieval Europe gradually developed a taste for distilled alcohol, at first generally in the form of liqueurs sweetened and flavoured by infusing leaves, etc., or by distillation from a mixture. More efficient distillation gave stronger distillates and eventually produced the aquavits and the brandy-wines, which are very strong indeed if drunk exactly as distilled. The abuse of these drinks is a part of social history. There was no dividing line between regimen and pharmacy in early times. The new strong drinks gave a feeling of warmth and well-being, which led to their being prescribed from the 14th century onwards for conditions producing feelings of chill and debility…so it is no accident that liqueurs and monasteries are commonly linked.”

Figure 1.2 The conjectural evolution of the still. From F. Greenaway et al., (ref. 3) and reproduced in F. Sherwood Taylor, Annals of Science, 1941–1947, vol. V.

And it is in a monastery that the story of Scotch whisky, at least, is said to start, which is discussed in detail in Chapter 2.

1.2 IRELAND

The history of Irish distilling is a long, tangled and unfortunate one, containing a salutary warning against complacency, yet with a happy ending.

Most histories of whisky place its first arrival in Europe in Ireland and then Scotland, with Irish Christian monks having obtained the secrets of distilling from the Moors in Spain, which they then brought home. Though the principle of distillation was known to the Arabs, the process by which it was transferred cannot be documented or even dated with any certainty and, in any event, it is far from clear that early distillation was used for the production of beverage alcohol, in fact it is frequently and convincingly argued that it was used in the making of medicines or perfumes.

It is not disputed that Irish monks travelled widely and gathered learning from a number of different sources. The monasteries they created were religious centres but also places of great culture. Many maintained hospitals to treat the local population and knowledge of the ‘water of life’ would have been greatly prized. But, as well as a medicine, its use as a restorative would have been soon appreciated, especially in Ireland's damp climate.

Moreover, it promoted a fighting spirit as, according to legend, King Henry II's troops discovered in 1170 when they invaded Ireland to boost the cause of the King of Leinster, who was at war with Roderic O'Connor, the High King of Ireland. Later, Sir Robert Savage of Bushmills is said to have given his men “a mighty draught of uisce beathe” as they went into battle in 1276.

There is a recipe for distilling from 1324 in the Red Book of Ossory – mainly a collection of Latin verses complied by Bishop Richard Ledred – but, frustratingly, it describes the distillation of wine which, of course, results in brandy. In 1405, it is recorded that Richard MacRanall, Chief of Mainter Eolais, died from an overdose of uisge beatha – but as to who made it and how we are left wanting.

So to the Scots and to Friar John Cor goes the honour of the first written mention of the production of whisky but, notwithstanding that, most writers agree that the prize for the earliest European distillation of a spirit that we can relate to whisky goes to the Irish. Having occupied Ireland in 1170, King Henry II appointed his son, John, as Lord of Ireland, and by 1177 the country was directly controlled by the English king. However, following the devastation of the Black Death, English influence diminished to the point where they had little control ‘beyond the Pale’, a fortified area round Dublin, central English authority having withered away to little or nothing in the country.

There, outside the reach of the English tax collectors, distilling quietly flourished. Just as in Scotland, distilling was an everyday and unremarked fact of the rural economy and the life of any substantial house. Attempts to raise tax were frustrated and this situation was to continue until King Henry VIII's invasion and subsequent domination of Ireland from 1536. Henry VIII then took a more practical view of the matter, attempting to raise tax and introducing a limit of one licensed distiller in a borough, with substantial fines for anyone caught producing illicitly. Following his dissolution of the monasteries, there was a further dissemination of the skills of distilling and the relevant technology – in 1541 his successor, Queen Elizabeth I, is said to have received (and more importantly enjoyed) a Bishop's gift of a cask of whiskey. The story is widely repeated in whisky histories; however, as she was 8 years old at the time, perhaps it was enjoyed more by her courtiers than the Queen herself!

By 1577, Raphael Holinshed praised aqua vitae in his Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland, by remarking: “truly it is a sovereign liquor if it be orderly taken”. During the long Anglo-Spanish war, a failed Spanish invasion in 1601 soon led to a period of complete English dominance in Ireland and, in 1608, a system of licensing was introduced under King James I of England and VI of Scotland.

The indefatigable Elizabethan traveller, Fynes Moryson, who was employed in Ireland around 1600 later wrote 4 that “the Irish aqua vitae, vulgarly called usquebagh, is held the best in the world of that kind, which is made also in England, but nothing so good as that which is brought out of Ireland. And the usquebagh is preferred before our aqua vitae, because the mingling of raisins, fennel seed, and other things, mitigating the heat, and making the taste pleasant, makes it less inflame, and yet refresh the weak stomach with moderate heat and good relish”.

The quality and appeal of whiskey had not escaped the sharp eyes of the English administrators in Ireland's ruling class. Bishop George Montgomery wrote to his sister in November 1607 with a seasonal gift of Irish whiskey:

“I am appointed a Commissioner for the plotting and devvyding of the contreye (i.e. Ulster), which I feare mee will keep mee here this Christmas agaynst my will; and agaynst my will it shal be indeed yf I eat not som of my coson's Beaumont's Christmas pyes, and so tell her I praye you. I hope my sister and she have received the water I sent them in a little runlet of a pottle, a quart for a peece”.

Famously, Sir Thomas Phillips paid 13 shillings 4 dimes for the right to distil for Coleraine and the Route. To this day, Bushmills have the date of 1608 embossed on their bottles, though this is a generous view of the distillery's foundation. In any event, the privilege was cancelled in 1620 following complaints of abuse and favouritism. A tax of 4 pence per gallon was introduced on Christmas Day 1661 and, under this Act, Excise Commissioners were appointed for the first time with authority to appoint gaugers and searchers. Their effectiveness was limited, however, as the rule of law in Ireland was patchy at best, especially in more remote country areas, and with few records it is hard to reliably estimate the extent to which distilling was carried out at this time.

The situation changed with new laws in 1717, 1719, 1731, 1741, 1751, 1759 and...