eBook - ePub

Complete Guide to Making Wooden Clocks, 3rd Edition

37 Woodworking Projects for Traditional, Shaker & Contemporary Designs

John A. Nelson

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 250 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Complete Guide to Making Wooden Clocks, 3rd Edition

37 Woodworking Projects for Traditional, Shaker & Contemporary Designs

John A. Nelson

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Learn how to construct a variety of traditional, Shaker, and contemporary clocks, with plans, parts lists, and instructions for 37 timepieces, including grandfather clocks, mantel clocks, and desk clocks.Complete Guide to Making Wooden Clocks, 3rd Editionalso includes a bonus pattern pack with scroll saw project templates.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Complete Guide to Making Wooden Clocks, 3rd Edition als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Complete Guide to Making Wooden Clocks, 3rd Edition von John A. Nelson im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Tecnología e ingeniería & Oficios técnicos y manufactureros. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

CHAPTER 1

A Brief History of Clocks

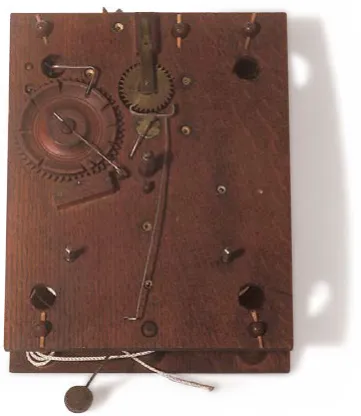

The theory behind time-keeping can be traced back to the astronomer Galileo. In 1580, Galileo, who is well-known for his theories on the universe, observed a swinging lamp suspended from a cathedral ceiling by a long chain. As he studied the swinging lamp, he discovered that each swing was equal and had a natural rate of motion. Later he found this rate of motion depended upon the length of the chain. For years he thought of this, and in 1640, he designed a clock mechanism incorporating the swing of a pendulum. Unfortunately, he died before actually building his new clock design.

In 1656, Christiaan Huygens incorporated a pendulum into a clock mechanism. He found that the new clock kept excellent time. He regulated the speed of the movement, as it is done today, by moving the pendulum bob up or down: up to “speed-up” the clock and down to “slow-down" the clock.

Christiaan’s invention was the boon that set man on his quest to track time with mechanical instruments.

EARLY MECHANICAL CLOCKS

Early mechanical clocks, probably developed by monks from central Europe in the last half of the thirteen century, did not have pendulums. Neither did they have dials or hands. They told time only by striking a bell on the hour. These early clocks were very large and were made of heavy iron frames and gears forged by local blacksmiths. Most were placed in church belfries to make use of existing church bells.

Small domestic clocks with faces and dials started to appear by the first half of the fifteenth century. By 1630, a weight-driven lantern clock became popular in the homes of the very wealthy. These early clocks were made by local gunsmiths or locksmiths. Clocks became more accurate when the pendulum was added in 1656.

Early clock movements were mounted high above the floor on shelves because they required long pendulums and large cast-iron descending weights. These clocks were nothing more than simple mechanical works with a face and hands and were called “wags-on-the-wall.” Long-case clocks, or tall-case clocks, actually evolved from the early wags-on-the-wall clocks. They were nothing more than wooden cases added to hide the unsightly weights and cast-iron pendulums.

JOHN HARRISON (1693–1776)

Little is known about this man, the one person who, I think, did the most for clock-making. John was an English clockmaker, a mechanical genius, who devoted his life to clock-making. He accomplished what Isaac Newton, known for his theories on gravity, said was impossible.

John Harrison was born March 24, 1693, in the English county of Yorkshire. John learned woodworking from his father, but taught himself how to build a clock. He made his first clock in 1713 at the age of 19. It was made almost entirely of wood with oak wheels (gears). In 1722 he constructed a tower clock for Brocklesby Park. That clock has been running continuously for over 270 years.

One year later, on July 8, 1714, England offered £20,000 (approximately 12 million dollars) to anyone whose method proved successful in measuring longitude. Such a device was desperately needed by navigators of sailing vessels. Sailors during this time were literally lost at sea as soon as they lost sight of land. One man, John Harrison, felt longitude could be measured with a clock.

John Harrison

During the summer of 1730, John started work on a clock that would keep precise time at sea—something no one had yet been able to do with a clock. In five years he had his first model, H-1. It weighted 75 pounds and was four feet tall, four feet wide and four feet long. To prove his theory, John built H-2, H-3 and H-4.

His method of locating longitude by time was finally accepted and he won the prize. It took him over 40 years. Today, his perfect timekeeper is known as a chronometer.

CLOCKS IN THE COLONIES

In the early 1600s, clocks were brought to the colonies by wealthy colonists. Clocks were found only in the finest of homes. Most people of that time had to rely on the church clock on the town common for the time of day.

Most early clockmakers were not skilled in woodworking, so they turned to woodworkers to make the cases for them. These early woodworkers employed the same techniques used on furniture of the day. In 1683, immigrant William Davis claimed to be a “complete” clockmaker. He is considered to be the first clockmaker in the new colony.

Great horological artisans immigrated to the New World by 1799. Most of these early artisans settled in populous centers such as Boston, Philadelphia, New York, Charleston, Baltimore and New Haven.

Clock-making grew in all areas of the eastern part of the colonies. The earliest and most famous clockmakers from Philadelphia were Samuel Bispam, Abel Cottey and Peter Stretch. The most famous clockmaker was Philadelphia’s David Rittenhouse. David succeeded Benjamin Franklin as president of the American Philosophical Society and later became Director of the United States Mint.

Most Early American clocks had wooden gears, as brass was very expensive and hard to obtain.

NINETEENTH CENTURY GRANDFATHER CLOCKS

Inexpensive tall-case clocks were made in quantity and became more affordable after 1800. The clock-making industry spread to the northeastern states. In Massachusetts, Benjamin and Ephram Willard became famous for their exceptionally beautiful long-case clocks. In Connecticut, mass-produced long-case clocks were developed by Eli Terry.

In early days, almost all clock cases were made by local cabinetmakers. A firm that specialized in clock works fashioned the wood or bronze works. Cabinetmakers engraved or painted their names on the dial faces, thereby taking claim for the completed clocks.

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, regular factory working hours and the introduction of train schedules, standardized timekeeping became a necessity. Clock-making moved to the forefront.

Wooden movements were abandoned in 1840 and 30-hour brass movements became popular. They were easy to make and inexpensive. Spring-powered movements were developed soon after. A variety of totally new and smaller clock cases appeared on the market.

NINETEENTH-CENTURY MANUFACTURERS

Clock manufacturers were mostly individual clockmakers of family-owned companies. After 1840 however, Chauncy Jerome built the largest clock factory in the United States. He started shipping clocks all over the world. The Jerome Clock Company motivated the organization of the Ansonia Clock Company and the Waterbury Clock Company. These three companies, along with Seth Thomas Company, the E. N. Welch Company, the Ingraham Clock Company, and the Gilbert Clock Company, became the major producers of clocks in the nineteenth century. There were over 30 clock factories in this country by 1851. From 1840 up to 1890, millions of clocks were produced in this country, but unfortunately, very few still exist intact today.

Elias Ingraham

Elias was born in 1805 in Marlborough, Connecticut. He served a 5-year apprenticeship in cabinetmaking in the early 1820s. By 1828, at the age of 23, Elias was designing and building clock cases for George Mitchell. When he was 25 years old, he worked for the Chauncey and Lawson Ives Clock Company, which was still designing and building clock cases.

Elias formed a new company with his brother Andrew in 1852 called the E. and A. Ingraham and Company, but 4 years later, it went bankrupt. A year later he formed his own company with his son, Edward. Changing the name to E. Ingraham and Company, the business began ...