1Away with All Rules?

Schein—Artistic illumination; the sheen of natural beauty; surface semblance; illusion; veil; husk; the quivering of life; the flicker of aesthetic categories; an image of freedom; the promise of reconciliation; harmony.

“As soon as the feeling opens up a path to us, then away with all rules” (

Sobald das Gefühl uns einen Weg eröffnet, fort mit allen Regeln). Never take composers at face value. Beethoven’s comment, from his letter of 6 July 1825 to Prince Galitzin, seems to propound the commonplace that expression is achieved by breaking rules (see Lockwood 2002: 89–91). The trope certainly accords with the reception of his last works by his contemporaries, who had difficulty understanding them in terms of the forms, or “rules,” of Classical convention. It fits the perception, popular in the nineteenth century, and still with us today in concert program notes, that, as Carl Dalhaus puts it, “Beethoven’s forms ‘shattered’ under the force of expression” (1989: 86). Yet Beethoven embeds his remark in the context of his discussion of voice leading and functional harmonic progression, explaining to Galitzin a distinction between

and

chords. As Lockwood observes, Beethoven’s letter, in which he demonstrates an analytical preoccupation with details of motivic working, voice leading, and harmony, is a “rare jewel” in Beethoven scholarship (90). “Away with all rules” must thus be taken with a good pinch of salt; on the level of technical grammaticality, Beethoven is anxious to appear to keep within convention.

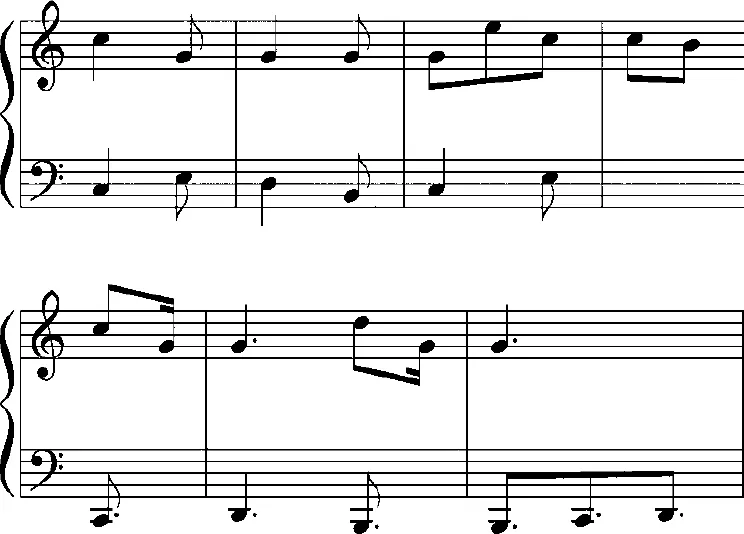

More broadly, Beethoven’s innocent remark to Galitzin, so straightforward in itself, surely misrepresents the apparent normalcy of much of his late music. Take the

Arietta from his last piano sonata, Op. 111 in C, which seems merely to reiterate tonics and dominants—the very building blocks of the language (

ex. 1.1). If the harmony is stereotypical, then the melody is a cliché, closely resembling the workaday tune which the publisher Diabelli supplied Beethoven for another variation set. Rather than subverting these conventions, the

Arietta projects them with newfound clarity, so that they shine. It is this very directness, even nakedness, of expression which gives the

Arietta its quality of a “little song” without words. What a shock, then, to discover that the

Arietta’s normalcy is predicated on utter contradiction at a foundational level of its syntax. Scrutinized more carefully, the tonics and dominants projected by the melody are disposed in such a way that it is impossible to decide which comes first: that is, whether the melodic G’s of mm. 1 and 2 express chords I or V. The ambiguity turns on the nature of upbeats. A basic knowledge of the Classical style tells us that upbeats, when they begin a movement, are conventionally unharmonized, as in Diabelli’s waltz. The job of an upbeat is to impart a metrical accent, a “kick,” to the first beat of the measure, the point where the bass comes in and the piece properly starts. Grounding the upbeat with a bass note in the left hand, as Beethoven does in the

Arietta, cuts across the bar line and short-circuits the anacrusis. Beethoven’s opening gambit profoundly shapes how we hear the harmony—and, of course, the subsequent variations built upon it. Ordinarily, the first bass note of m. 1 would sound like an accented neighbor to the D, so that the prevailing harmony in the measure is in fact a

dominant, rather than a tonic (this effect is enhanced when the C is sharpened in variation I, m. 17; even more so with the

inversion of variation II, m. 33). But grounding the upbeat with a deep C anchors the C of m. 1 and tilts the harmonic center of gravity from the dominant toward the tonic. Thus

neither harmony—dominant nor tonic—ultimately prevails; instead, the two are locked into a delicate equipoise. To grasp what is so distinctive about this equilibrium, one need only compare it with the so-called “bitonal” harmony of twentieth-century composers such as Stravinsky, by which chords or keys were stacked above each other. The

Arietta is not “bitonal” in this respect, since the chords never properly clash. We hear, rather, a flicker of interpretive perspectives, as in the famous rabbit/duck illusion: now the chord is a tonic, now it is a dominant, but never both at once. Because this “flicker” is in principle endless, never susceptible to a definitive interpretation, Beethoven’s harmony is notionally beyond analysis—an enterprise which depends on synchronic “snapshots” of musical structure, such as Schenkerian graphs. In his profound analytical study of the sketches (1976), William Drabkin plausibly graphs the

Arietta as a Schenkerian initial ascent from C to G (or

to

), albeit with some distinctive gaps seminal for the theme’s subsequent career in the variations. He also reviews how the genesis of the piece oscillated between tonic and dominant beginnings, as if Beethoven couldn’t make up his mind whether to start the theme with a I or a V.

Example 1.2a indicates that Beethoven’s upbeat had originated as a full tonic measure.

Example 1.2b, conversely, shows a sketch closer to the final version, with a tonic upbeat to a full measure of dominant, yet missing the crucial tonic suspension in the bass. It is the introduction of this suspension which affects the final version’s tonic/dominant ambiguity. The ambiguity could be said to absorb the

Arietta’s dynamic genesis into the music’s fabric. Analysis is powerless to model this continuity between genesis and structure. If traditional methods are unable to account for the

Arietta’s harmonic “flicker,” what can?

Example 1.1. Piano Sonata in C, Op. 111, second movement, mm. 1–4

Example 1.2. Beethoven’s sketches for his Arietta (transcribed and numbered by Drabkin)

a. No. 37, mm. 1–4

b. No. 51, mm. 1–2

The Arietta, normative at one level, paradoxical at another, exemplifies procedures which Beethoven developed in the last decade of his life. In the late style, musical categories which we blithely take for granted—“rules,” “expression,” “convention,” “coherence,” “process”—are thrown dramatically into doubt. Whereas innovative art is often held to elaborate, subvert, or deconstruct convention, Beethoven’s late style enshrines rules at their most fundamental. When musical conventions are subsumed within an original artistic process, we draw the irresistible analogy with language, in which words are transparent to the sense they express. By contrast, Beethoven’s conventions cloud over, looked at, not through, so that process unfolds within musical material, not across it, in a weird mixture of external rigidity and internal tension. He is not the first, or the last, artist to foreground the materiality of his idiom, a device better known in painting than in music. The bricks in De Hooch’s seventeenth-century courtyards are often more richly grained and “alive” than the human subjects who populate them. And much has been written about Van Gogh’s famous peasant shoes, whose expressiveness transcends their utilitarian function (see Heidegger 1975: 36; Derrida 1987). To some extent, Beethoven’s self-reflexivity—his “music about music”—follows in this tradition, except that music is abstract. To render musical material concrete, to even think of music as “material,” is a radical step. A chord, clearly, is not a brick or a pair of boots. Beethoven objectifies a rule, rather than a physical object proper, and that is far more disturbing.

Such observations are not obviously captured by music theory. If we are to unravel the significance of Beethoven’s achievement, and reactivate the metaphors sleeping within his casual references to the “rules” and “feeling” of music, we must stake out a broader interpretive context. A philosophy of Beethoven’s style makes the basic assumption that musical rules correlate both with social convention and with conceptual reason and are underpinned by certain natural categories of perception—in short, that musical material bears the imprint of society, mind, and nature. “Music as philosophy” is predicated also on the historical drama of modernism and the emergence of the autonomy principle in the late eighteenth century. According to this story, the formally abstract and self-contained (“autonomous”) Classical style of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven is celebrated as the benchmark for rationality in music, as well as the ideal balance of this rationality with the individual and societal dimensions of human subjectivity. With Beethoven’s late style, this utopian high-water mark in Western music encounters its catastrophe: a repertory which critically reflects upon the foundations of musical Classicism, while at the same time reconstructing them from a quite different position. Beethoven’s object, therefore, is nothing less than the foundation and limit of human reason itself. This, in a nutshell, is the gist of Theodor Adorno’s reading of the late style, the most influential and intellectually sophisticated interpretation we have. As well as a front-rank philosopher and cultural critic, Adorno was arguably the sharpest writer on music of the twentieth century. Anybody at all familiar with his writings will have recognized my account of the Arietta as surreptitiously Adornian in its focus on stylistic contradiction and formal disunity. Adornian also is my emphasis on the unresolved tension between convention and play, registered in the processual dynamic of our artistic cognition. What I informally term a “flicker” actually has a name in the Adornian tradition: Schein, a Hegelian concept which mixes the notion of artistic “semblance” with the glimmer of the numinous in the Romantic symbol. In his fragmentary essay on Schein, Walter Benjamin, a key influence on Adorno, talks of the vital “quivering” of aesthetic beauty:

No work of art may appear completely alive without becoming mere semblance [Schein], and ceasing to be a work of art. The life quivering in it must appear petrified and as if spellbound in a single moment. The life quivering within it is beauty, the harmony that flows through chaos and—that only appears to tremble. What arrests this semblance, what holds life spellbound and disrupts the harmony, is the expressionless [das Ausdrucklose]. That quivering is what constitutes the beauty of the work; the paralysis is what defines its truth. (2002: vol. 1, 224)

As regards the music, Schein—an attribute of beauty in all art, and hence a background foundational quality—is objectified in late Beethoven on the level of grammatical contradiction. As regards the theory, the trembling which Schein describes besets the identity of the concept itself—the interplay between its various aspects of “illumination,” “semblance,” “surface,” and “harmony” (see the epigraph which begins this chapter), as well as its relationship within a family of cognate, yet distinct notions, including Erscheinung, Apparition, phenomenon, and phantasmagoria (extending ultimately to complex questions from the philosophy of consciousness and Marxist ideology critique). Furthermore, the stylistic contradictions which Benjamin describes as arresting or paralyzing the harmony of Schein seem in late Beethoven to be just another, more dramatic, expression of this same “quivering.” Strangely, the late style’s oppositional flicker appears to embrace the very interruptions of this flicker, so that the music’s “beauty” and “truth” are thrown into a dialectical dance, becoming, as Adorno discovered, far less separable from each other than Benjamin suggests. In short, the ambiguity which I hear as being the late style’s most beguiling aspect spreads out from the music to encompass both philosophical categories such as Schein and the very relationship between these categories and the music: between music and philosophy.

Beethoven and Adorno

The title of my book nods at the title of the Beethoven monograph Adorno labored on for much of his life, and which he left unfinished at his death. The publication of Beethoven: Philosophie der Musik in 1993, edited by Rolf Tiedemann, called for a response on a larger scale than the still-continuing spate of review articles. Given that Adorno is best known to musicians as a critic of twentieth-century music, a theorist of musical modernism centered around the Second Viennese School, here is a chance to nudge the “center” of critical theory back to its true origin—the musical enlightenment of the Classical style, and the Classical composer who occupies the highest plinth in Adorno’s pantheon: Beethoven. This book is basically an extended reflection on the significance of Adorno’s critical theory to tonal music. In some ways, I attempt a mediation of Adorno’s insights within a musicological and music-theoretical culture he did not live to see. Such an exercise begs the question of method. What, precisely, are musical conventions, and how, exactly, do we analyze them? The analytical portions of Adorno’s Beethoven are primitive, and he had a limited historical grasp of Beethoven’s roots in eighteenth-century style—an irony, given his emphasis on the role convention plays in the late style. The work of Classical scholars such as Allanbrook, Ratner, Rosen, Webster, and many others has enormously enriched our understanding of the facts of the Classical style: the normativity underlying Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven’s individual genius. Likewise, we have benefited from theories which study style from the perspective of musical perception and cognition, particularly the work of Leonard Meyer and Eugene Narmour. These facts and theories were simply unavailable to Adorno. Likewise, Adorno had a problem, practical as well as philosophical, with music analysis. Not only did he misunderstand Schenker, he also mistrusted the hermeneutic side of critical enquiry—its dependence on conventional frameworks of interpretation. One can make too much of the conflict between philosophy and music analysis, caricaturing it as an opposition between the negativity of thought and the positivism of facts. Much recent work in the philosophy and history of music theory has helped bridge this gap. As quickly as I write this, however, I hasten to add that Adorno cannot be translated into music without missing the entire point of philosophy’s critical autonomy as a perspective onto music “from the outside.” And vice versa: eliding or assimilating the two removes music’s viewpoint on philosophy. Their reciprocal, yet independent, relationship is at the heart of Adorno’s vision of music’s place in the world. I employ the facts of modern musicology and analysis rather as an illumination of Adorno’s ideas. Conversely, Adorno’s ideas illuminated my own, many of which were gained before I read a word of his writings. Some of these ideas are developed in my previous book on music and metaphor (2004). It is interesting that Adorno’s key concept in his discussion of late Beethoven is allegory, metaphor’s dark twin. In this respect, the present book is essentially about allegory in music, and thus a (critical) complement to my (hermeneutic) study of metaphor.

If Adorno cannot be simply cross-checked against the score, then a parallel and even greater danger is to misrepresent the complexity of his thought as a series of slogans or “buzzwords.” Adorno does utilize an identifiable array, or, to use Walter Benjamin’s term (1998: 34), a “constellation” (1998: 34), of concepts—“mimesis,” “ratio,” “mediation,” “material,” “language character,” “concept character,” “apparition,” “caesura,” “breakthrough,” Schein, etc. But these terms draw their meaning from their position and interaction within the entire constellation; it is extraordinarily difficult both to extract a single term from the network and to pin it down with a stable definition. Benjamin’s analogy that “Ideas are to objects as constellations are to stars” (34) is a good way of imagining the loose and mobile relationship between general and particular (as in Wittgenstein’s comparable notion of the crisscrossing “family relationships” which connect “language games”).1 According to Adorno’s very German notion of thought (i.e., philosophy), categories are kept constantly in motion within the process of reflection. It is particularly hard to separate the spirit from the letter of Adorno’s writings (by which they resemble music), and many musicologists who claim to be broadly influenced by Adorno end up just extracting the jargon from the context. This includes a recent study of the late quartets purporting to be a “translation of Adorno’s philosophy of music into actual analysis” (Chua 1995: 6). Another symptom of this syndrome is the co-option of Adorno as an outrider for postmodernism, a New Musicologist avant la lettre. Adorno was actually profoundly hostile toward the various tendencies which have coalesced into a “postmodern theory,” not least in his commitment to the principle of musical autonomy. Autonomy, a bankrupt concept for postmodernism, continues nevertheless to hold sway in a parallel tradition of German social thought, in which the Enlightenment Project is alive and well. The writings of post-Adorno critical theorists such as Jürgen Habermas, Karl-Otto Apel, and Albrecht Wellmer suggest that the New Musicological consensus that we live in a post-Enlightenment world is both negotiable and contestable.2 The defense of musical autonomy does not mark out Adorno as a desiccated formalist—how could ...