The Rio do Peixe basin comprises four sedimentary sub-basins: the Sousa, Triunfo (also called the Uiraúna-Brejo das Freiras basin), Pombal, and Vertentes (fig. 1.1). They are located in the western part of the Brazilian State of Paraíba, in the municipalities of Sousa, São João do Rio do Peixe (a small city formerly called Antenor Navarro), Aparecida (formerly a district of Sousa), Uiraúna, Poço, Brejo das Freiras, Triunfo, Santa Helena, and Pombal. In the first two basins—Sousa and Uiraúna-Brejo das Freiras (Triunfo), especially the Sousa basin—an abundant tetrapod ichnofauna have been preserved, consisting of footprints and trackways, mainly of large theropods, sauropods, and ornithopods. Invertebrate ichnofossils, such as traces and burrows produced by arthropods and annelids, are also common (Fernandes and Carvalho 2001). Along with the formation’s dominant reddish color, typical of subaerial environments, there are some units of greenish shales, mudstones, and siltstones, where body fossils are present. These include ostracods, conchostracans, plant fragments, palynomorphs, fish scales, and bone fragments of crocodylomorph, dinosaurs, and probably pterosaurs.

Figure 1.1. Location map of the Rio de Peixe basins, western Paraíba, Northeast Brazil (Carvalho et al. 2013a).

Figure 1.2. Location map of the Rio do Peixe basins, western Paraíba, Northeast Brazil, and the distribution of its local ichnofaunas (Leonardi and Santos 2006). The smaller maps are redrawn from Leonardi and Carvalho (2002).

Sousa (fig. 1.2) and Uiraúna-Brejo das Freiras (Triunfo) are intracratonic basins in Northeast Brazil that developed along preexisting structural trends of the basement during the opening of the South Atlantic Ocean. The age of sedimentary deposits in these basins, based on ostracods (Sousa et al. 2019) and palynological material, is characteristic of the Rio da Serra (Berriasian to Hauterivian) and Aratu (early Barremian) local stages (Lima and Coelho 1987; Regali 1990).

Sedimentation in these basins was controlled by regional tectonic processes (Lima Filho 1991). During the Dom João time (Purbeckian Stage), due to crustal extension, sigmoidal basins were developed at the inflection of the NE–SW and E–W faults. During the Rio da Serra time (Berriasian to Hauterivian), under the same tectonic stress pattern, the basinal areas increased, and their shapes became rhomboidal. In the last stage, probably at the end of Aratu time (early Barremian Stage), there was a change in the tectonic pattern, and sediment accumulation began to diminish.

These deposits reflect direct control of sedimentation by tectonic activity. Deposition occurred along the faulted borders of the basins as alluvial fans, changing to an anastomosing fluvial system more distally. In the central region of the basins, a meandering fluvial system with a wide floodplain was established, where perennial and temporary lakes developed (Carvalho 2000a).

The paleontological-geological relevance of the Sousa and Uiraúna-Brejo das Freiras basins is the abundance of dinosaurian ichnofaunas that represent parts of an extensive Early Cretaceous megatracksite (Viana et al. 1993; Carvalho 2000a; Leonardi and Carvalho 2000, 2002) established during the early stages of the South Atlantic opening. In this area, 37 sites and approximately 96 individual stratigraphic levels preserve occurrences of more than 535 individual dinosaurian trackways as well as rare tracks and traces of the vertebrate mesofauna.

The Town of Sousa

The Brazilian town of Sousa (fig. 1.3) is indisputably the “capital” of the “valley of the dinosaurs” of western Paraíba. The Sousa municipality (Ferraz 2004) currently has a territory of 842 km² (square kilometers) and is situated in the region of the Alto Sertão da Paraíba (the inner semiarid belt of Paraíba). It is bounded on the north by the municipalities of Vieirópolis, Lastro, and Santa Cruz; on the east by São Francisco and Aparecida; on the south by São José da Lagoa Tapada and Nazarezinho; on the southwest by Marizópolis; on the west by São João do Rio do Peixe (formerly Antenor Navarro); and on the northwest by Uiraúna.

The town of Sousa is located at 220 meters (m) above sea level, at (GPS datum: SIRGAS 2000) S 06 45.505, W 38 13.797 in the town center; at 420 kilometers west (as the crow flies) of João Pessoa, capital of the State of Paraíba. The town is crossed by the Peixe River (Rio do Peixe), a tributary of the Piranhas River (named Açu River in its lower reaches in Rio Grande do Norte); this latter river also crosses the territory of the municipality of Sousa.

Figure 1.3. The town and the territory of Sousa, the “capital” of Dinosaur Valley, seen from the Precambrian hill called Benção de Deus, north of Sousa.

The municipality of Sousa had (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística—IBGE, 2019) 69,444 inhabitants, 51,881 of whom live in the town of Sousa. The main access to the town is by car or bus from João Pessoa, along federal highway BR-220. The town of Sousa, through its mayors and administrations, is in many ways one of the most important supporters of the research that led to this scientific study.

The main occurrence and most readily accessible site of dinosaur footprints is at Passagem das Pedras (Ilha Farm) in the Sousa municipality; it is now a natural park. In December 1992, through a state act, the area was defined as a natural monument and named “Dinosaur Valley Natural Monument” (Monumento Natural Vale dos Dinossauros) (fig. 1.4).

Figure 1.4. Cretaceous Park at Sousa, with Carvalho, at the main gate.

History of the Paleontological Site

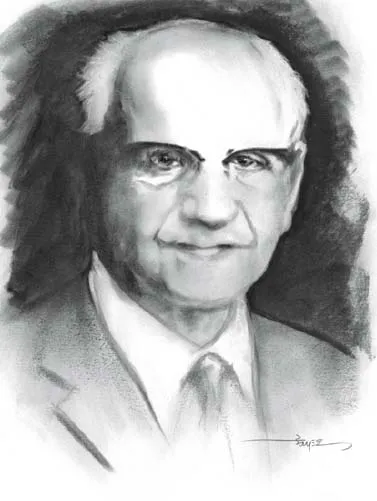

In the 1920s, Luciano Jacques de Moraes (1896–1968), a Brazilian mining engineer (fig. 1.5), was working for the DNOCS (Departamento de Obras contra as Seccas, the Department of Works against the Drought), surveying the then little-known Brazilian northeast. In the western area of the State of Paraíba, on the Ilha Farm, Moraes discovered 2 trackways impressed in the rocky pavement forming the riverbed of Rio do Peixe, a left tributary of the Piranhas River. They were 2 crisscrossing trackways of different size, made by very different animals. They were also the first fossil tetrapod trackways published from Brazil.

Figure 1.5. Luciano Jacques de Moraes (1896–1968), a Brazilian mining engineer, discoverer of the first 2 short trackways impressed in the rocky pavement forming the bed of the Peixe River, at Passagem das Pedras in the Ilha Farm, sometime before 1924. These were the first tetrapod trackways published from Brazil. Art by F. Fayez.

Moraes surveyed the tracks and later, with the help of Oliveira Roxo (Divisão de Geologia e Mineralogia, DGM), he correctly attributed the trackways to the Dinosauria. Moraes sent a slab containing a footprint (the sixth in the sequence) excavated from trackway SOPP 2 and a plaster cast of a footprint from trackway SOPP 1 to the United States to be studied by an unnamed paleontologist; he had not received an acknowledgment when he published his book in 1924, nor did he ever receive a reply. It seems probable that he had sent the tracks to the American Museum of Natural History in New York (this was a common opinion at the Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral—DNPM—in the 1970s), but they were not found there by Leonardi in 1985. In his book, Moraes questionably attributed trackway SOPP 1, the largest, at that time 13 m long and with 15 footprints, either to a member of the Stegosauria or, as a less likely alternative, to the Ceratopsia; evidently, he interpreted this as the trackway of a quadruped. Probably he interpreted the true footprints themselves as impressions of the forefeet and the displacement rims, with their roundish collapsed mud cracks, as hind-foot prints. Moraes identified the maker of trackway SOPP 2 as a bipedal dinosaur without deciding between the Theropoda and the Ornithopoda. Moraes described the tracks with rare thoroughness, providing detailed drawings and good photographs. He also estimated the sizes of the presumed trackmakers, according to his different hypotheses about their nature. This was a good work for that time; however, Moraes was neither an ichnologist or a paleontologist, and his drawings were rather inaccurate. Among other things, he did not see the true fore prints of the semibipedal maker of SOPP 1.

Moraes eventually sent some photographs to Friedrich von Huene of Tübingen (1875–1969; fig. 1.6), who published, instead of the photos, some drawings from Moraes’s (1924) book in his paper on new fossil tetrapods from South America (1931). He briefly described both tracks as digitigrade; wisely avoiding instituting new taxa, von Huene described SOPP 1 as the trackway of a quadruped with total overlap of manus and pes prints and the SOPP 2 as having been made by a biped. He tentatively attributed the first trackway to either a ceratopsid or a nodosaurid but preferred the latter; the second trackway he attributed to an ornithopod, more specifically to the trachodontids or kalodontids. His identifications were based largely on Moraes’s unpretentious drawings.

Von Huene had worked in the field in Brazil in the 1920s but had never visited Paraíba. Brazilian geologists and paleontologists—among them the late Llevellyn Ivor Price (1905–1980; fig. 1.7), Diogenes de Almeida Campos, and Jannes M. Mabesoone—saw Moraes’s tracks in the 1950s and 1960s. However, these tracks were not further studied or published, except for a br...