![]()

1

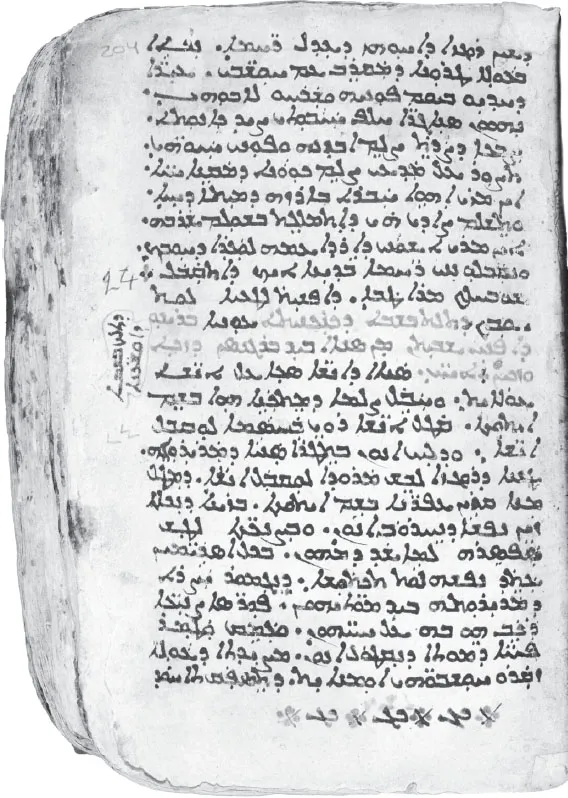

SYRIAC

Introduction and Bibliography by J. Edward Walters

Traveling east and slightly north from Syrian Antioch, ancient travelers would have come to the magnificent city of Edessa in the kingdom of Osroene, which occupied a strategic location on the Roman-Parthian (and later Roman-Sassanian Persian) border. Edessa was a cosmopolitan city, located along a major east-west trade route, and well known as a home to many gods and the diverse peoples who were devoted to them. Although the sources are difficult to trust as straightforward records, it seems that Edessa served as a gateway for early Christian expansion to the east. Edessa was also the home of the dialect of Aramaic known as Syriac, which would become the primary literary language for Christianity in Mesopotamia for several centuries. Further to the east, not far from Edessa lay the city of Nisibis, an ancient fortified city that is perhaps most well known as a territory lost by the Roman Empire in the aftermath of the defeat and death of Emperor Julian at the Battle of Samarra in 363 CE. As a result of the treaty signed by Julian’s successor, Jovian, the Persian King Shapur II, who had failed on three previous siege attempts against Nisibis, took control of the city without having to destroy its walls, while the Christian community in Nisibis was forced to relocate across the Roman border, namely back to cities like Amida and Edessa.

Among those Christians who were exiled from Nisibis was a theologian and poet who would come to be known as Ephrem the Syrian. Ephrem’s influence on the Syriac traditions of Christianity cannot be overstated. His theology permeates the Syriac liturgies, and his unique expressions and turns of phrase are echoed throughout later Syriac authors. His signature composition style, a metrical structure known as a madrāšā (frequently translated “hymn” but perhaps more accurately rendered “teaching song”), became a standard genre of Syriac literature. In both prose and poetic compositions, Ephrem is also one of the most significant Syriac sources for three teachers who would ultimately come to be regarded as heretics by Christians, but who also had significant communities of followers in Ephrem’s time: Bardaisan, Marcion, and Mani. These texts serve as valuable witnesses—albeit one-sided, polemical witnesses—to the beliefs and practices of these communities in the fourth century.

Ephrem also had a significant impact on the development of biblical exegesis in the Syriac tradition, as his poetic teaching songs displayed a unique creativity with interpretation, sometimes in the form of invented dialogue for biblical characters. This style of poetic exegesis allowed Syriac authors to creatively embody characters, often giving voice to figures—especially women—who are relegated to silence in the biblical text itself. It is also likely that at least some of these poems were performed by women in liturgical settings. Later Syriac authors also continued to develop their own form of poetic meter for biblical interpretation and homilies. In particular we may mention authors like Jacob of Serugh and Narsai of Nisibis, who each perfected the syllabic homily for their own exegetical purposes. Although his name is certainly not commonly known among historians of Christianity, it is estimated that Jacob of Serugh has the third largest surviving corpus of homilies from early Christianity across all languages, behind only John Chrysostom and Augustine of Hippo.

These two authors, Jacob and Narsai, are notable for another reason: though their careers overlap, they represent two distinct emerging traditions of Syriac Christianity that put them on opposite sides of a significant theological dispute that forever altered the ecclesiastical context for Syriac Christians. The impetus for this change was, of course, the christological disputes set off by Nestorius, the bishop of Constantinople, who infamously argued that Mary, the mother of Jesus, should not bear the title theotokos (“God-bearer” or “Mother of God”) because, according to Nestorius, such a title unnecessarily collapsed and confused the divine and human natures of Christ. Nestorius soon found himself the object of significant backlash, led by Cyril of Alexandria. The resulting controversy spawned not one, but two councils: the Council of Ephesus (431) and the Council of Chalcedon (451). It would be impossible to summarize these complicated events in this short introduction, but the following points are pertinent to Syriac Christianity.

The key issue at stake in the two councils was the question of the human and divine natures of Christ and what language was appropriate for describing them. One side of the debate, represented by Nestorius and his deceased teacher, Theodore of Mopsuestia, argued that Jesus’s human and divine natures remained distinct (and thus they were called dyophysites, meaning “two natures”). The other side, represented by Cyril of Alexandria and his supporters, argued that it was heretical to distinguish too sharply between the natures because it implied not just two natures, but two “persons” in Christ. The theological statement produced by the Council of Chalcedon attempted to resolve this issue with a conciliatory position that Christ is “acknowledged in two natures … in one person and one hypostasis.” While the ratification of this formulation at the council did succeed in giving Christians a new theological articulation, it failed to convince everyone. In fact, not only did the new statement not pacify the dyophysites who were loyal to Theodore and Nestorius, it also sparked a reaction from the opposite end of the spectrum: the miaphysites, who argued that the “in two natures” language of the Chalcedonian formula misrepresented the Christology of Cyril of Alexandria (who had died in 444, several years before the council). The miaphysite position argued, contra both Nestorian dyophysites and Chalcedonian dyophysites, that the union of divine and human natures in the incarnate Christ did not permit anyone to speak of them as distinctly two natures in the person of Christ; thus, they argued for one united nature after the incarnation (subsequently they were called miaphysites, meaning “one nature”).

Thus, in the aftermath of the Council of Chalcedon, there were three distinct confessions: (1) those who supported and affirmed Chalcedon, primarily made up of Christians within the bounds of the Roman Empire, (2) the non-Chalcedonian dyophysites (who are often called “Nestorians”), who were primarily located in Persia, and (3) the miaphysites, who were concentrated in the eastern Mediterranean, stretching from Egypt, through Syria, and into Armenia. Throughout the sixth century, these distinct theological positions hardened in opposition to each other, forming distinct communities of Christians with separate leadership and hierarchical structure. Thus the end result of this controversy was the origin of several unique Christian church organizations that were not in communion with one another: (1) the Chalcedonians (who would separate later into the Byzantine Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic traditions), distinguished by the affirmation of the Council of Chalcedon, (2) the Assyrian Church of the East (the non-Chalcedonian dyophysites), and (3) the various miaphysite confessions that formed among linguistically diverse communities: Syriac Orthodox Church, Armenian Orthodox Church, Coptic Orthodox Church, and Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Thus, after the fifth century, Syriac authors are universally designated by which tradition they represent: West Syriac (Syriac Orthodox), East Syriac (Assyrian Church of the East), or Melkite (i.e., the Syriac and later Arabic speakers who supported Chalcedon). Mention should also be made of the Maronite tradition, which is another branch of early Syriac Christianity distinct from the East and West Syriac churches who remained in communion with the Chalcedonian tradition. Maronites remain as a distinct tradition today, concentrated in Lebanon. As time went on, there were further geographic and theological fragmentations of these branches.

The geographic dispersion of Syriac-speaking Christians meant that individual communities faced very different political situations, even at contemporaneous times. For example, while Christians in the Roman Empire enjoyed the ascendance of Christian political power with Constantine and his successors, Christians in the Sassanian Empire remained a religious minority who were often at odds with their political leaders. As a result of these circumstances, the martyrdom genre became a significant feature of Syriac literature, resulting in a sizable corpus known as the Persian Martyr Acts. Historians of Christianity are likely very familiar with the persecutions associated with the Roman Emperors Decius and Diocletian, but comparatively far less is known about the persecution associated with Shapur II or Yazdagird I. At the same time, it is also important to remember that there were Syriac-speaking Christians within the Roman Empire, as evidenced both by the existence of the Melkite tradition mentioned above and by many miaphysite Christians finding themselves persecuted as heretics by their own emperor, Justinian. It is often tempting to collapse “Syriac Christianity” with something foreign to the context of the Roman Empire, but this erases communities who existed as both Romans and Syriac Christians. Moreover, as seen in the Letter on the Ḥimyarite Martyrs (translated in this volume), Syriac-speaking Christians well beyond th...