eBook - ePub

Literary Translation

A Practical Guide

Clifford E. Landers

This is a test

Buch teilen

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Literary Translation

A Practical Guide

Clifford E. Landers

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

In this book, both beginning and experienced translators will find pragmatic techniques for dealing with problems of literary translation, whatever the original language. Certain challenges and certain themes recur in translation, whatever the language pair. This guide proposes to help the translator navigate through them. Written in a witty and easy to read style, the book's hands-on approach will make it accessible to translators of any background. A significant portion of this Practical Guide is devoted to the question of how to go about finding an outlet for one's translations.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Literary Translation als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Literary Translation von Clifford E. Landers im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Sprachen & Linguistik & Übersetzen & Dolmetschen. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Techniques of Translation

Decisions at the outset

Even before beginning to tackle a text, the translator faces several crucial decisions of great importance to the final product. Awareness of these pivot points is fundamental to adopting a strategy for the project, and each translation requires an approach that takes into account the specific challenges of the SL text. What works for one writer may not function well for another. Some texts will call for adaptation rather than straightforward translation. Should the author be encouraged to participate, and if so, at what stage?

Fluency and transparency

The prevailing view among most, though not all, literary translators is that a translation should reproduce in the TL reader the same emotional and psychological reaction produced in the original SL reader. Thus, if the SL reader felt horror or curiosity or amusement, so should the TL reader. This approach is not without its hazards, for the question arises as to whether a translator is obligated to reproduce boredom, incoherence, unintentional grammatical lapses, factual errors, etc.

Most translators judge the success of a translation largely on the degree to which it ‘doesn’t read like a translation.’ The object is to render Language A into Language B in a way that leaves as little evidence as possible of the process. In this view, a reader might be unaware he/she was reading a translation unless alerted to the fact. Whether adopting this perspective or not, upon beginning a project the translator must decide to what point transparency is a desideratum. Although the majority of readers hold it to be perhaps the single most important aspect of a ‘good’ translation, the view among translators, especially academics, is less unanimous. Scholars are more receptive to a visible role for theory in the production of a translation, and this raises the question of how much translation theory you need to be a translator.

How much understanding of the theory of the internal combustion engine do you need to drive a car? Theory and practice are two different entities, though there comes to mind the hoary definition of an economist as a person who sees something work in practice and wonders if it will work in theory. While I have no quarrel with theorists, they work a different side of the street; I am first and foremost a practitioner and have yet to meet a working translator who places theory above experience, flexibility, a sense of style, and an appreciation for nuance.

There is no inherent problem with theory per se, but when it interferes with translational output, either by reducing productivity of negatively impacting the final result, we are on shakier ground. No one complains that the many translators who work without a conscious theoretical basis are thereby somehow impugning theory; contrariwise, overly zealous application of theoretical guides can wreak havoc with a translation. One example, discussed later in this section, is the doctrine known as ‘resistance,’ whose best known advocate is Lawrence Venuti of Temple University.

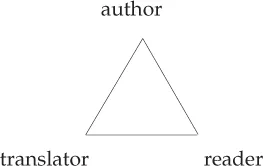

In the time-honored author/translator/reader triangle, many would interpret this modus operandi as placing consideration for the author (as representative of the source culture) above that of the reader. The question naturally arises: who other than scholars would want to read prose that bears the heavy imprint of foreign grammar, idiom, or syntax? Examples of this literalistic approach might be ‘a seven-headed beast’ (Portuguese for a daunting or difficult task) or ‘from the same field a berry’ (Russian for six of one, a half dozen of the other). Well, it might work in theory…

The author–translator–reader triangle

It is almost a cliché for the relationship between author, translator, and reader to be represented graphically by an isosceles triangle:

The underlying concept is that ideally the translator maintains equal proximity to the author (or the SL text) and to the reader (the final product, the TL text). Fine in theory but, as will be seen, the reality of in-the-trenches translating usually results in a lopsided triangle at best. Moreover, real-world translating means there is an irregular swing, sometimes in a single paragraph, between favoring the author and favoring the reader. If the translator must ‘privilege’ (appalling piece of jargon!) either the author or the reader, how is a balance struck?

Perhaps a more accurate depiction of the author–translator–reader relationship might be a simple linear one:

author ——— translator ——— reader

This has the advantage of placing the translator more realistically in an intermediate position between SL author and TL reader, for without the intervention of the translator the author would be unable to reach the TL audience. At the risk of straining the analogy, we could think of the lines joining the three as elastic, at times bringing the translator closer to the author, at times narrowing the distance between translator and reader. Let’s examine how this works in practice.

‘Targeteers’ and ‘sourcerers’

The two approaches boil down to what the always sound Peter Newmark calls ‘targeteers’ and ‘sourcerers.’ Targeteers, obviously, are TL-oriented, while sourcerers are SL-oriented. As Umberto Eco has said:

A source-oriented translation must do everything possible to make the B-language reader understand what the author has thought or said in Language A… If Homer seems to repeat ‘rosy-fingered dawn’ too frequently, the translator must not try to vary the epithet just because today’s manuals of style insist [otherwise]. The reader has to understand that in those days dawn had rosy fingers whenever it was mentioned, just as these days Washington always has DC.

In other instances, Eco continues, translation is rightfully targetoriented. In Foucault’s Pendulum, one of the characters cites a phrase from a poem by Giacomo Leopardi, ‘al di la della stepe,’ literally ‘beyond the hedge.’ Eco’s purpose was ‘to show how Diottallevi could experience the landscape only by linking it to his experience of the poem. I told my translators the hedge was not important, nor the reference to Leopardi, but it was important to have a literary reference at any cost.’ The ensuing English translation by William Weaver reads, ‘We glimpsed endless vistas. “Like Darien,” Diottallevi remarked…’

But how does a translator discover whether he or she is one or the other, or perhaps a hybrid of both? Complicating the issue is the fact that what Newmark calls ‘authoritative’ texts, because of the literary or political importance of their author, demand a close translation, even when the result may sound a bit eccentric. As Andrew Hurley, who retranslated the complete short story oeuvre of Jorge Luis Borges, has intimated, one proceeds with extreme caution before opting to, say, rearrange word order in Borges.

Academicians tend more toward the sourcerer approach, surely a reflection of their rigorous research orientation stressing the primacy of meaning. With no intention of offending my professorial colleagues, candor compels me to concede that a lifetime of reading reams of scholarly articles is hardly the best preparation for producing smooth, transparent prose. This is an unfortunate fact of life, because college faculties tend to be over-represented among literary translators, for reasons mentioned elsewhere in this guide. While a significant number of the most accomplished translators have come from the halls of ivy, other academicians have foisted upon the reading public some of the driest, most awkward, most impenetrable prose imaginable, all in the interest of being ‘faithful’ to the original.

Resistance

Then there is the problem of ‘resistance.’ At the risk of oversimplifying, resistance is the concept that a translation should patently demonstrate that it is a translation. A less-than-perfect fit (the argument goes) is the ‘resistance’ of the SL culture and SL language to being shoehorned into a dissimilar cultural-linguistic frame. Translators who follow resistance theory deliberately avoid excluding any elements that betray the ‘otherness’ of the text’s origin and may even consciously seek them out. Smoothness and transparency are therefore undesirable and even marks of a colonizing mentality. The reduced readability of the final product is an indication of its fidelity to the source language and the culture in which it originated. Advocates of resistance might be termed the radical fringe of literary translation.

Murat Nemet Nejat has put it this way: ‘A successful translation must sound somewhat alien, strange, not because it is awkward or unaware of the resources of the second language, but because it expresses something new in it.’

My opinion is that there is little to be gained from skewing a translation to make it sound odd. Oh, a confirmed sourcerer might answer, what if the original itself sounds odd? What about your obligation to the author?

I acknowledge the translator’s duty to the author just as I recognize that same translator’s accountability to the TL reader. But I believe that of the two, the targeteer better meets both responsibilities. Here’s my reasoning:

Authors’ interest in being translated is related to their desire to achieve exposure in a foreign culture by appearing in another language. For writers from languages of limited diffusion, breaking into print in English – and to a lesser extent in any of the major European languages like French or German – can mean the difference between being known only in their native land and becoming the next Umberto Eco or Gabriel García Márquez. Monetary rewards for the author, not so incidentally, are also proportional to the total number of readers in the TL, if the book is lucky enough to catch on. Whatever your feelings about the movie version of The Name of the Rose, it is a virtual certainty the film would not have been made had the novel never appeared in English.

But publication in translation is only the first step. If the author appears to the TL public as inaccessible or esoteric, the end product may be merely a succès d’estime. Further, while SL readers may be forgiving of, or even oblivious to, small idiosyncrasies in the author’s style, TL readers are less tolerant. Worse, any deviation from ‘normal’ usage is likely to be chalked up as a shortcoming of the author, poor work by the translator, or both, when in reality it is an artifact of the structure of the SL culture.

Did Pushkin, Baudelaire, or Ibsen sound strange in the original? Lofty, certainly; inspired, absolutely; but not odd. A literal rendering of any world-class writer invariably makes that individual sound tongue-tied, as if he or she were speaking a foreign language, and poorly at that. ‘Resistance’ of this kind, I contend, often places cultural and academic considerations so far ahead of literary and aesthetic concerns as to distort the TL reader’s perception of the author. Why bother with a masterpiece from another language if it reads like a trot?

Here, from an insightful article by Margaret Sayers Peden, one of the finest translators of Spanish and Latin American literature, is an excellent example of a trot:

‘A su retrato’ is one of Sor Juana’s most widely anthologized poems and pursues themes common to her writing and to the writing of her age: the treachery of illusion and the inevitability of disillusion.

Este, que ves, engaño colorido,

que del arte ostentando los primores,

con falsos silogismos de colores

es cauteloso engaño del sentido:

que del arte ostentando los primores,

con falsos silogismos de colores

es cauteloso engaño del sentido:

este, en quien la lisonja ha pretendido

excusar de los años los horrores,

y venciendo del tiempo los rigores,

triunfar de la vejez y del olvido,

excusar de los años los horrores,

y venciendo del tiempo los rigores,

triunfar de la vejez y del olvido,

es un vano artificio del cuidado,

es una flor al viento delicada,

es un resguardo inútil para el hado:

es una flor al viento delicada,

es un resguardo inútil para el hado:

es una necia diligencia errada,

es un afán caduco y, bien mirado,

es cadáver, es polvo, es sombra, es nada.

es un afán caduco y, bien mirado,

es cadáver, es polvo, es sombra, es nada.

This, that you see, colored (false appearance) fraud (hoax, deception), which of art showing (exhibiting, bragging) the beauty (exquisiteness), with false (treacherous, deceitful) syllogisms of colors

is cautious (wary, prudent) fraud (hoax, deception) of the sense (reason):

this, on which flattery (adulation) has attempted (claimed, sought) to excuse (avoid, prevent, exempt) from years the horrors (fright, dread), and conquering (defeating, subduing) from time the rigors (severity, cruelty)

triumph from (over) old age (decay) and forgetfulness (oversight, oblivion),

is a vain (empty, futile) artifice (trick, cunning) of care (fear, anxiety),

is a flower on the wind (air, gale, breeze) delicate (refined, tender),

is a useless (fruitless, frivolous) guard (defense) for fate (destiny):

is a foolish (stupid, injudicious) diligence (activity, affair) erring (mistaken),

is a worn out (senile, perishable) anxiety (trouble, eagerness), and, well considered

is a cadaver (dead body), is dust (powder), is shadow (shade, ghost, spirit),

is nothing (nothingness, naught, nonentity, very little).

… [T]he trot is an act of pure violence performed on a literary work. It destroys the integrity of the sonnet, reducing it an assemblage of words and lines that may convey minimal meaning, but no artistry.

In my view, in all too many cases what seems to be ‘resisted’ is the beauty of the author’s mode of expression.

All in all, it’s in the author’s and the reader’s interest for the translator to lean toward the latter in case of doubt. I remember Theodore Savory’s aphorism in The Art of Translation: ‘The original reads like an original: hence it is only right that a translation of it should too.’ Or, as Eugene Eoyang has put it, ‘Something simple and inevitable in one language may be difficult in another language with the same simplicity, yet there is no reason for that difficulty in the process of translation to be reflected in the text of the translation. Art in translation is that which hides art.’ Thus my identification with the targeteers. In short, I resist resistance; literary translation is hard enough without intentionally introducing elements of obfuscation.

Word by word or thought by thought?

Independent of the ongoing debate about the optimal approach to translation, the practitioner must establish certain principles when beginning a project. One of these is to determine what the translation unit is to be. Is it the word, the sentence, the paragraph, or none of the...