![]()

1Investigating Interdependence and Literacy Development in Heritage Language Speakers: Theoretical and Methodological Considerations

Raphael Berthele and Amelia Lambelet

Multilingualism, Transfer and Literacy Development

Bilingualism and multilingualism in migrant children has been a research topic in applied linguistics for many years (see Polinsky & Kagan [2007] for an overview). The sociolinguistic situation of children who are confronted with a minority language at home (their heritage language) and a majority language in their everyday life has also been widely documented and compared to other types of bilingual and multilingual development (Montrul, 2012). Historically, linguists’ engagement with the topic has gradually developed from deficit views to a resource-oriented view. Deficit-oriented views put the emphasis on the difficulties encountered by these multilingual children, as the term ‘incomplete acquisition’ (Montrul, 2008) suggests. Some authors even argued that in certain contexts, individuals fail to develop functional skills in either of their two languages, as in the semilingualism view advocated by Hansegård (1975; see discussion of this notion below). The resource-oriented views, on the other hand, put the emphasis on the possibilities that bi- and multilingualism enable (e.g. Gawlitzek-Maiwald & Tracy, 2005). This positive view of multilingualism puts the emphasis on the potential of transfer on different levels: on the linguistic level and on the level of strategies of language learning and use. Today, it is quite common in scholarly debate to stress this positive transfer potential together with the idea of an added value of being bi- or multilingual (e.g. in the domain of cognitive control cf. Bialystok et al. [2004]; but see also Paap & Greenberg [2013] for a critical discussion of the evidence on the bilingual advantage).

The purpose of this book is to describe migrant children’s language development, and in particular the potential residing in shared or transferred resources between their heritage languages and the languages spoken in the region where their family has immigrated. More precisely, the focus of the book lies on the development of their literacy skills in both languages. In this book, we refer to literacy as the skills necessary for reading and writing, although we are well aware of the fact that it is ‘impossible to give a clear and bounded definition of [it]’ (Brockmeyer & Olson, 2009: 4). Our take on literacy is deliberately focusing literacy as a skill (Baker, 2006: 321), although we are aware that other, more critical and more wide-ranging approaches to literacy (e.g. New London Group, 1996; Street, 2006) have been proposed. We chose our focus to match the literacy objectives of the educational systems in which our studies are situated. Skills required in such ‘traditional’ reading and writing tasks are considered central in educational selection, which justifies the focus in the research reported in this book.

Thus, this book contributes to the scholarly investigation of the potential beneficial effects in academic proficiency across languages in migrant children. After addressing the most central terminological and theoretical issues (Chapter 1), we discuss evidence from four empirical studies on heritage language speakers in different educational and linguistic contexts (Chapters 2–9). The common research goal of all studies was to understand the factors, both linguistic and non-linguistic in nature, that contribute to the development of language skills in the heritage and the school languages. To use a term that is well established in the literature in this field, the research presented in this book attempts to assess the level of ‘interdependence’ of different languages in the individual multilingual speakers’ repertoires.

The theories and terminology used in this book mainly stem from bilingualism and heritage language speakers research. However, since in most situations discussed, more than two languages are part of the speakers’ repertoires, we also draw on multilingualism research. Therefore, the participants in the studies are referred to both as ‘multilinguals’ and as ‘bilinguals’. All participants in the studies presented in this book are multilinguals with at least three languages or varieties in their linguistic repertoires: their heritage language(s), their language of instruction, often a local dialect in informal communication (e.g. Alemannic Swiss German) and additional foreign languages taught at school. The children in the non-heritage language comparison groups use a repertoire composed of at least the latter two languages and varieties. The authors of this book also use the terms ‘bilingualism’ and ‘bilinguals’ since in all research projects the focus lies on two particularly important languages in this repertoire, the language of instruction and the heritage language.

The deficit-oriented view of bi- and multilingualism, the semilingualism concept, has been questioned by bilingualism scholars (MacSwan, 2000; Martin-Jones & Romaine, 1986). Most contemporary scholars working on bi- and multilingual development tend to emphasise the futility of comparisons of bi- or multilingual repertoires to idealised monolingual norms, since bilingualism and multilingualism unavoidably lead to a different type of language competence (Bley-Vroman, 1983; Cook, 2002; Grosjean, 1985, 1989; Herdina & Jessner, 2002). This is often done by explicitly referring to the idea of crosslinguistic influence and transfer across languages (Jarvis & Pavlenko, 2007) and/or to resources shared by all languages in the repertoire (Cummins, 1980, 2005). As discussed in the section ‘Metaphor of Transfer’, it is often difficult to clearly distinguish the idea of transfer and the idea of interdependence of languages in the repertoire in the scholarly literature.

As the literature in this field often construes the notion of transfer very broadly, including the effects of a common underlying proficiency for academic language use that are the typical instantiations of linguistic interdependence (see Cummins, [1980] 2001: 131), it is important to start by clarifying the theoretical foundations and the terminological conventions adopted for our book.

The metaphor of transfer

The literature on transfer and interdependence involves a confusing degree of conceptual and terminological heterogeneity due to various reformulations and revisions of some of the central ideas. Our intention in this chapter is not to give a comprehensive account of the various versions of the hypotheses of the dynamics within the bilinguals’ or multilinguals’ languages. The main goal is instead to discuss the most central assumptions underlying transfer and interdependence research and to come up with a suitable set of terms for the discussion of the empirical research presented in this book.

The notion of transfer in second language acquisition (SLA), third language acquisition (TLA), multilingualism research and bilingualism research is always metaphorical. Literal transfer would mean that a linguistic phenomenon is taken from a donor language and carried into another (receiving) language, and is thus no longer present in the source language. Instead, most definitions of transfer capture processes such as copying (Johanson, 2002) or the replication (Matras, 2009) of matter or patterns of the model or source language in the replica or target language. The term ‘pattern replication’ refers to the replication of a (semantic or syntactic) feature of the model language using matter of the recipient language. The term ‘matter replication’ refers to the replication of morphemes, words or even longer chunks from a model language in a receiving language – an example of matter replication is the emergence of loanwords in language contact situations. An example of ‘pattern replication’ is discussed in Berthele (2015): multilingual speakers of Romansh, when speaking Swiss German, tend to replicate the semantic category represented by a general verb ‘metter’ (‘to put’) in their dominant language Romansh. They do this by overgeneralising a German-caused posture verb ‘legen’ (‘to lay’ [transitive]), even when referring to events where monolingual speakers of German use other caused posture verbs such as ‘setzen’ (‘to sit’ [transitive]) or ‘stellen’ (‘to stand’ [transitive]). Depending on the normative point of view, such differences in the use of German can be considered ‘deviations from the monolingual norm’ or, within a multicompetence view of bi- and multilingualism, as ‘convergence’. As research on bilinguals consistently shows, bilingualism both entails the borrowing of linguistic matter from one language into the other, as well as the convergence of linguistic patterns, e.g. on the level of syntax (Jarvis & Pavlenko, 2008) or semantics (Berthele, 2012; Lambelet, 2012, 2016).

However, many influential definitions of transfer, e.g. the one by Odlin quoted below, include a wide variety of phenomena beyond matter and pattern replication:

Transfer is the influence resulting from similarities and differences between the target language and any other language that has been previously (and perhaps imperfectly) acquired. (Odlin, 1989: 27)

Odlin’s definition regards transfer in a much wider sense by including target language use patterns that can be explained very generally as the influence of the coexistence of two languages in the bi- or multilingual repertoire. Avoidance of constructions that are different (and perceived difficult) in the target language is an example of transfer in the wider sense: a multilingual might deliberately avoid the French ‘il faut que…’ (It is necessary/obligatory that…) that requires a subjunctive form of the subordinate clause if she or he is uncertain about the correct subjunctive morphology of that particular verb (see Laufer and Eliasson [1993] for a study of lexical avoidance). Other examples are stylistic and pragmatic choices. For instance, in the argumentative letters collected in the Heritage Language and School Language: Are Literacy Skills Transferable? (HELASCOT) research project (see the section ‘Outline of the Book’ and Chapters 2 and 5 of this book), some participants used emotional and affective ways of addressing the addressee for their letters to have more impact. As this socio-pragmatic plus often appears in both of the participant’s languages, it could be argued that this particular pragmatic competence is transferred from one language to the other, or at least that it forms part of some kind of trans-linguistic pragmatic competence. This example illustrates the difficulty of distinguishing transfer in the wider sense from the idea of common underlying resources for two or more languages.

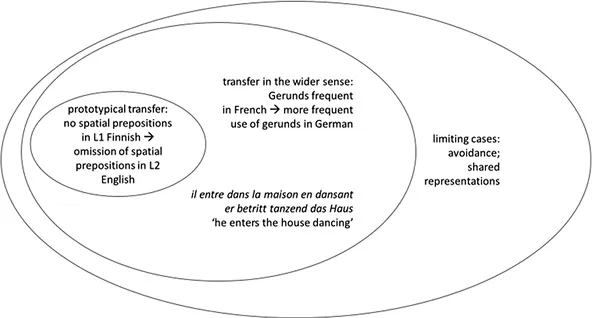

Figure 1.1 The radial category ‘transfer’. The prototypical example is inspired by Jarvis and Odlin (2000) and the example ‘transfer in the wider sense’ is by Berthele and Stocker (2016)

As a preliminary conclusion, we argue that the notion of transfer in bi- and multilingual repertoires can be considered a radial category with relatively good examples (prototypical transfer, transfer in the narrow sense) at its centre, and less typical examples (transfer in the wider sense) and fuzzy boundaries where transfer and shared resources overlap (see Figure 1.1).

Odlin’s definition quoted above covers both positive and negative transfer (Odlin, 1989: 36). As can be observed in production data from many different types of multilinguals and second language (L2) users, there is ample evidence for negative and positive transfer (for a review, see Pavlenko & Jarvis, 2002). Positive transfer potentially occurs when t...