THE CONCEPT OF A PARADIGM IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND THE NEED TO SYSTEMISE EXISTING TREATISES ON CONTROL

Science as a practice relies strongly on social approval. The word ‘science’ emerged in the English language during the Middle Ages by way of French, and was soon given a connotation of accurate and systemised knowledge. Being most often dated back to Aristotelian thinking of knowledge by the early Latin translators, one was claimed to have reached scientific knowledge when he was able to prove that he had arrived at it demonstratively – most often through an exercise of deductive logic. With the growing discoveries in physics during the nineteenth century, the word ‘science’ started quickly to lose its previous common meaning – science was now to be dominantly related to natural and physical sciences (Ross, 1962). The reason behind the latter emerges from the belief that by their nature and through the experimental methods natural and physical sciences manage to offer ‘an objective way of looking at the world’ (Hassard, Kelemen, & Cox, 2008, p. 17).

Yet a book by Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), anchored ‘Truth’ into a new meaning. Truth, instead of being external to human activities and just ‘out there’, is more and more accepted as basing itself as ‘a matter of community acceptance’ (Goles & Hirschheim, 2000, p. 251) or ‘a process of consensus formation’ (Anderson, 1983, p. 25), resulting scientific practices to be a matter of good persuasion rather than proof. According to Kuhn (1962), science as a social convention bases itself on paradigms – ‘universally recognized scientific achievements that for a time provide model problems and solutions to a community of practitioners’ (p. viii).

Kuhn ushered, in a remarkable new understanding, of how scientific communities work, but overall, tackles the grand question, what is science as such? He himself sees science as a social activity. By the definition, the production of knowledge in scientific communities needs the acceptance from the community or as Cuff, Payne, Francis, Hustler and Sharrock, (1984, p. 191) put it, ‘scientists are socialised into particular academic cultures’, where they develop a commitment to particular ways of viewing and approaching their subject matter. To take a note from Ritzer (1975, p. 166), paradigms are most of all useful heuristic services for understanding the nature of a particular science. Authors such as Pfeffer (1993) have even gone so far that to state how paradigm purity might be even a sign of scientific maturity within a particular field of study (Hassard et al., 2008, p. 1). In fact, Pfeffer (1993) has stated how fragmentation of organisational sciences is a severe threat to the growth of the field and the consensus about grounding assumptions within a paradigm is essential to the meaningful development of a strong paradigm.

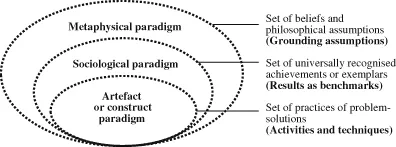

With the help of Masterman (1970), it is possible to identify three main groups of understandings of the notion of a paradigm. First of all, a paradigm might be interpreted as a set of beliefs about one’s subject matter. Masterman (1970, p. 59) has called this notion a metaphysical paradigm, since it aims to represent kind of a global perspective or worldview. Thus, a paradigm is a construct that comprises a specific set of philosophical assumptions (Mingers, 2003, p. 559). The second understanding sees paradigm as a sociological paradigm – paradigm as universally recognised achievements or exemplars. Third, artefact or construct paradigm, which most of all reflects science as puzzle-solving activities, instruments and tools that are considered valid scientific rigor. All the listed types of paradigms can be seen as having different scopes where broader ones comprise narrower ones (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Nesting of Paradigms.

Source: Compiled by the author.

For the current book, the author will seek to comprise all the mentioned three understandings of a paradigm, since in reality all these levels of paradigms are tightly interconnected. Hence, the definition of a paradigm might be stated as a set of coherent philosophical assumptions that manifest in recognised scientific achievements and influence acknowledged practices of problem solutions.

The growing dissatisfaction with the dominant, modernist orthodoxy proposed by natural sciences on social sciences came clearly apparent during the 1970s (Willmott, 1993a, p. 681) and can be witnessed in the works of Silverman (1969, 1978). While Kuhn (1962) described science as the competition of the fittest paradigms (e.g. the shift from the Ptolemaic model to the Copernican, and further to Newton’s paradigm), where scientists act like puzzle solvers, Silverman (1969, 1978) took another point of departure and stated how puzzle solving in natural and social sciences is completely different. The most obvious difference being the object of study itself. Refuting the idea that social and natural sciences could always be approached with the same dominant orthodoxies in research, Silverman (1978, p. 126) builds his logic on the fact that social sciences seek to understand action and behaviour, and while doing so, individual action can never be separated from the wider context.

Considering the differences between the natural and social sciences, it is unrealistic to expect that the natural science paradigms should perfectly manage to explain highly complex and constantly changing organisational realities, or to make meaningful predictions on individual behaviour (Griffiths, 1999). Acknowledging this, some authors such as Koontz (1961), Scott (1961), Silverman (1969), Effrat (1972) and Ritzer (1975) have fostered a debate on suitable paradigms for social sciences and made clear attempts to develop a typology of paradigms existing in social sciences. Still, through reflections over the ‘critical mass’ or root assumptions within a paradigm (that differentiates paradigms from each other) did not emerge until Burrell and Morgan’s book Sociological Paradigms and Organisational Analysis (1979). As Jackson and Carter (1991, p. 109) have stated, Burrell and Morgan (1979) set to provide a framework which would clarify the complex relationship between ‘competing claims about organisations’. Markedly, they managed to show how studies in social sciences are not competing with each other as who is closer to the truth, but instead, existing studies, representing different scholarly communities, have different perspective and understanding of the research phenomena. That said, depending on the community, one can develop vastly different assumption, approaches and assessment criteria.

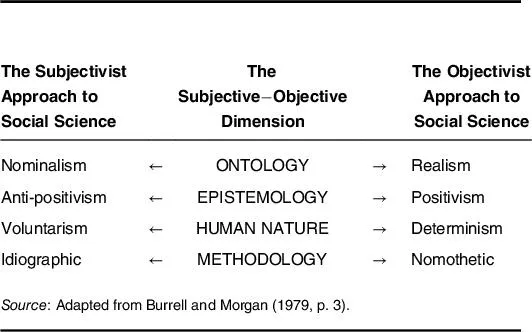

Across the decades, there have been great debates over the basic assumptions that are the cornerstone of the paradigm and ultimately allow us to differentiate between the paradigms. Burrell and Morgan (1979), who took that social theory can be conceived in terms of the nature of social sciences and the nature of the society based their work on four assumptions – ontology (assumptions which concern the very essence of the phenomena under investigation), epistemology (assumptions about the grounds of knowledge), methodology (assumptions about obtaining knowledge about the social world) and human nature (assumptions with regard to the relationship between human beings and their environment). The first three – ontology, epistemology and methodology – are widely used notions from the philosophy of science that have proved to be very useful for organising dimensions of research. Depending on what kind of worldviews ontological assumptions reflect, one may witness a wide spectrum of groundings for knowledge about the social world, debating between whether and to what extent can human beings achieve adequate knowledge that is independent of their own subjective construction (Morgan & Smircich, 1980). In a similar vein, as objectivists require science to be based on methods that are grounded on publicly observable and replicable facts, subjectivists believe that the essential characteristic of human behaviour lies in its subjective meaningfulness and therefore social sciences cannot neglect the aspects of meaning and purpose in human behaviour (Diesing, 1966). Setting the basic assumptions into the classical polarised subjective–objective continuum, Burrell and Morgan (1979) propose a schema (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. A Schema for Analysing Assumptions about the Nature of Social Science.

According to Burrell and Morgan (1979), ontological assumptions may vary from one extreme to another, from nominalist to realist approach. Nominalism stating how the external world is negotiated without any certainty of anything besides the structures of our individual cognition (hence, in science universally valid claims or knowledge is considered as too bold a statement), and realism proposing that the social world exists independently of human beings and has a reality of its own (the aim of science is to develop objective and universal claims of how things are). This kind of opposing view of the relationship between the human being and the world presents great differences how scientist perceives the object of study, including whether the researcher and the study can or should be independent from each other.

As ontology reflects the views how scientists conceive the world, differences here also imply different grounds for claiming knowledge about those worlds (Morgan & Smircich, 1980, p. 493). As for the dualistic continuum in epistemology, positivist epistemology has been grounded in natural sciences for a long time. A positivistic understanding asserts that ‘the growth of knowledge is essentially a cumulative process in which new insights are added to the existing stock of knowledge and false hypothesis eliminated’ (Burrell & Morgan, 1979, p. 5). As a contrast, a subjectivist view of reality (of the world) or anti-positivist view would stress that the world is socially constructed (Morgan & Smircich, 1980), rather than objectively determined (Noor, 2008, p. 1602). From the latter, it follows that anti-positivists reject the belief that science could ever state to have been gained objective knowledge of any kind (Burrell & Morgan, 1979, p. 5), and that any knowledge developed from the study is highly dependent on the unique context that the research initially emerged from.

Dimension of human nature in Burrell and Morgan’s (1979) understanding reflects the exact relationship between the human being and the reality – whether the human being is determined by their environment or has the free will to act voluntarily, metaphorically set, human beings as ‘mere puppets’ or ‘free agents’. In conducting research, it makes a great difference whether we believe that human behaviour can be easily manipulated and studied (e.g. conducting enough surveys on work satisfaction, analysing the results and offering ways to improve the satisfaction), or human behaviour is so complex that at all times, we can never claim full knowledge, but also, human behaviour has an effect on the research as well (e.g. work satisfaction is deeply individual assessment, influenced by endless factors and is rarely the same today as it was perhaps yesterday).

A subjective approach to social science in methodological assumptions follows an idiographic perspective with a belief that one can understand the social world via obtaining first-hand knowledge of the subject under investigation while in contrast, a nomothetic perspective emphasises to base research upon systematic protocol and technique (Burrell & Morgan, 1979, p. 6). As an idiographic approach shows a tendency to specify one’s subject matter, nomothetic approach seeks to generalise one’s subject matter in order to provide law-like generalisations to the whole population.

Table 1.2 strives to illustrate the mentioned dimensions of research or assumptions by making brief connections to organisational control.

Table 1.2. Basic Assumptions or Dimensions of Research, Differentiated by the Approach to the Research.

Assumptions (or Dimensions of Research) | The Subjectivist Approach to Organisational Control | The Objectivist Approach to Organisational Control |

Ontology | Nominalism | Realism |

(The nature of the research object) | There is no universal organisational control, it is merely an abstract concept. Furthermore, organisational control is a social matter and social reality is always relative | Assumes rationality in human behaviour. Such rationality can be studied by a researcher via hypothesis testing. Organisational control and other social matters exist separate of individual human beings, thus are approachable in the same way as research objects in natural sciences |

Epistemology | Anti-positivism | Positivism |

(The knowledge of the research object) | Denial of universal knowledge. All knowledge of organisational control is particular and bound by uniqueness of the context. Here also the researcher is non-independent from the knowledge production process (e.g. organisational aspects such as meanings, symbols, identities are uniquely connected to the establishment of organisational control) | The belief in achieving valid and generalised knowledge of individual behaviour by collecting enough observations and developing patterns. Research is designed so that it was strictly independent from the researcher, and the new knowledge will be used to affect organisational arrangements (e.g. through annual work satisfaction surveys, management strives to gain universal knowledge of whether everything is still ‘under the control’) |

Methodology | Idiographic | Nomothetic |

(Approaching the research object) | The aim of the research is to discover uniqueness of individual experiences of organisational control. Thus, great efforts are given to the study of individual experiences. High dependence on inductive reasoning, detailed and mostly qualitative descriptions of the context (e.g. studying the individual experiences of the work satisfaction by unstructured interviews) | The aim of the research is to find regularities in human behaviour to produce law-like generalisations about organisational control. High dependence on deductive, mostly quantifiable reasoning and pre-set hypotheses from the previous literature (e.g. conducting online-based survey with pre-set and closed questions on the work satisfaction) |

Human nature | Voluntarism | Determinism |

(The nature of human being as an object of study) | Individuals in an organisation have an effect on established control systems. Thus, organisational control is never solely a managerial product, but is established and continuously transformed by interaction between management and employees | Individuals in an organisation are considered as passive bystanders and determined by their environment. By studying the regularities in their behaviour it is not only possible to predict future activities, but also to manipulate and fashion their behaviour into alignment with organisational goals |

Source: Compiled by the author.

Burrell and Morgan (1979) crossed basic assumptions from the philosophy of science with those about the nature of society. As nature of science was seen through a subjective–objective dimension, assumptions about the nature of society are regarded as a debate...