![]()

![]()

FIRST WORDS

Ann Lauterbach

Pretend you have never been told anything about poems or poets. In place of that pretense, try to recall a very early experience you had of reading or hearing language that interested or excited or confused or enlightened you. Maybe it was something you overheard, or something someone else read, or a comic-book, or a sign on a billboard. Now write about that experience, trying to describe what about the text got to you and why.

This assignment is motivated by my desire to trigger your initial awareness of language, whether written or spoken, without the pressure to impress anyone. I want to engender a sense of how individual and how essentially solitary our relation to words is, and to elicit responses that testify to a fundamental diversity of experience. In my writing classes, I had begun by asking each student to speak about his or her interest in literature and language, and the replies were remarkably flat and homogeneous, usually presented in terms of a social (i.e., “my third-grade teacher really liked my poems”) rather than a private encounter. Few students mentioned books or individual poems they had read or heard; the answers seemed guarded and not particularly germane. When I changed it to a written assignment, each student was permitted to retreat and inspect his or her attachment. The answers were, in fact, extremely varied and interesting, ranging from a mother’s spoken prayer over a crib to the arduous process of learning English in a foreign country (Japan). This exercise helps set the tone and terms for thinking about the ways in which reading and writing are intimately linked.

![]()

NOT-SO-AUTOMATIC AUTOMATIC-WRITING EXERCISE

Thomas Lux

The point of this exercise is to gather and then to cull, extract, from a large pile of stream of unconsciousness or automatic material the one or two ounces of goods that then might be applied to the writing of poems.

General Rule: Be prepared to do this exercise every day and if possible more than once a day for at least ten days. It can be done at any time (even at its lengthiest it will not take more than about twenty minutes) but it sometimes works better if it is done when one is, for example, tired, or just waking up, or agitated, or elated, etc. In other words, when one’s synapses might be a little askew, when one is not feeling most “average.”

RULES:

1. Start in the upper left corner of a page and write without stopping for a set period of time or until you reach a certain predetermined point on the page. It works better to use a typewriter because it is faster and also less of a physical strain, but it can also be done by hand. Keep it short, particularly at the beginning: five to seven minutes per exercise, a page maximum. Remember: once you start writing do not stop. Try to write concretely, sensorially, in images. Do not worry about “sense,” do not think, pay no attention, at this point, to grammar, punctuation, etc.

2. When the predetermined point on the page is reached or the allotted time is up, remove the paper from the typewriter. Do not read it. Put it away.

3. Do these exercises until you have approximately the equivalent of ten single-spaced typed pages. Gradually lengthen the time for each exercise but never more than twenty minutes or so.

4. Once you have the ten pages, read through them all and underline anything that seems in any way interesting, fresh, weird, reverberant. Trust your instincts. Some of the material will be strange, scary, truly bizarre. If you have followed the above rules, you will not even remember having written most of it.

5. Pull out these underlined fragments. Correct spelling, punctuation, etc. The fragments will probably range from single words to word couplings, to images, to passages running three to four lines long. Type the fragments double-spaced (so you’ll have room to make hand-written revisions). Maybe you’ll have one to two pages of these fragments now, out of the ten with which you began. Number the fragments.

6. Repeat rules 4 and 5, this time being a harder editor regarding what is truly interesting, loaded, fresh, etc. Change, add to, or cut words from fragments, listening to them a little for what they might be suggesting, where they might be trying to lead you. Now you might have less than a page of these fragments, maybe 1 or 2 percent of all the words originally written, a dozen fragments say. Renumber them.

7. Read them, listen to them: somehow numbers 1, 4, 7, 9, for example, will seem to belong together, be thematically/emotionally linked. Ditto numbers 2, 3, 8. Some might not seem to be connected to others but might seem to contain some seed of a poem, a title, a rhythm, etc. Some might be just beautiful, enigmatic orphans.

8. Put the fragments that seem to belong together on a page and use them as psychic notes to a poem. Make the conscious connections, put all the sweat in, do whatever work necessary to write a poem. Good luck.

The point of this should be obvious: to tap into unconscious material, figure out what from this huge swamp is potentially poetic material, and then to use it, add to it, change it, etc. Instead of beginning a poem with a memory or experience, you begin with something less obvious, less literal, and try to find what it was about it that made you write it in its first, roughest form. This is not automatic writing as the surrealists used the term. For them, the poem existed after the completion of rule 1. Nor is this exercise a method for writing poems, a formula—it is simply an exercise of discovery, a way of coming at the process of writing a poem that may help writers write poems they did not know they wanted or needed to write.

![]()

TRANSLATIONS: IDEA TO IMAGE

(FOR A GROUP)

Carol Muske

This is an exercise I’ve tried with students from preschool to MFA programs, mainly to prove that the mind does not “think” in abstractions.

I’d like you all to shut your eyes and I’ll say a word. Open your eyes and tell me what you “saw.” For example, if I say “justice,” you may see the lady with the scales or a judge with a gavel or a courtroom. This is the mind’s “translation” of an idea, an abstract concept to a mental picture, an image. The mind does this naturally.

For example:

LOVE | hearts, a loved one’s face |

DEATH | coffin, grave, tombstone |

SELF | mirror, photo, conehead |

SOUL | votive fire, black-eyed peas, god’s eye |

Please write down your “images.” Be honest about what you “see.” Don’t worry if you see a Brussels sprout when I say “self”—your mind is telling you something. It’s making a connection, which may not be readily apparent to you. There is no such thing as a non sequitur, the mind always has logic; it might not be obvious logic, but the mind has its reasons for connecting two seemingly unlike notions.

Let’s “track” this process a little bit. I once gave this exercise to first graders. A little girl responded to the word Happiness by writing, “I feel like a big orange sun is coming up inside my body.” I asked her to continue following this stunning visual presentation, and she described the sun heating up her toes, her shins, ascending through her body, blazing out of her head “like a sunflower,” and rising into the sky, where it became a “second sun” that pulled “the real sun” into it like a “black hole.” Not bad.

Regarding the “Brussels sprout” syndrome, the process is the same. If I say “self” and you see a Brussels sprout, continue to interrogate that image and write down the next image that it inspires, and the next. You may find that you are “tracking” the ignition of a poem—let’s say you see a hand picking up the broccoli, or a toy next to it. You recognize the hand as yours, your hand as a child, you begin to enlarge the frame, you see it’s you as a baby eating broccoli for the first time, conscious of being a separate (perhaps suffering!) being. Or the images keep coming and stay mysterious. That’s OK too, but keep the record, write down these signals from the unconscious. Writing is an intuitive process; we must trust our intuition.

The poet alone may find “Translations” a rewarding solo exercise, given the often hermetic nature of the evolving imagery and the frequent attendant feeling of unexpected personal revelation. Or, on a lighter level: personal “etymology” is fun; it’s exciting to track words to their surprising sources and can be an effective writer’s-block breaker.

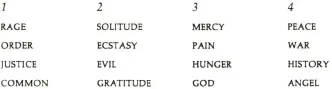

Here is a list of “abstractions” displayed in four columns, to enable the solo poet to play a kind of translation “solitaire.”

The idea is investigation: follow the thread back through the labyrinth to the literal referent (Minotaur?). Give yourself five minutes. Pick a word, at first glance, from each column, then write down all the non sequitur images you get for each one. See where this takes you. See what connections occur among the columns. Circle the words that seem...