eBook - ePub

Business Relationships with East Asia

Jim Slater, Roger Strange, Jim Slater, Roger Strange

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 288 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Business Relationships with East Asia

Jim Slater, Roger Strange, Jim Slater, Roger Strange

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

This volume analyses the business environment in East Asia with reference to trade and investment flows within the region and between East Asia and Europe. Focusing on the two-way flow of management ideas, investment and technology, this study highlights the way in which both sides can benefit.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Business Relationships with East Asia als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Business Relationships with East Asia von Jim Slater, Roger Strange, Jim Slater, Roger Strange im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

1 Introduction

Jim Slater

A widespread implicit belief in both Europe and East Asia is that the ‘other’ region is homogeneous. Visitors are often dismayed to discover that both are equally diverse linguistically, culturally and economically. This diversity complicates business decision-making and increases the need for accurate intelligence. The authors’ hope is that this book will assist in the requisite environmental scanning. The emphasis here is on conditions in East Asia, rather than on Europe. None of the studies is specifically concerned with Japan. Even though roughly one-third of the papers presented at the conference in Birmingham, which forms the basis of this collection, were concerned with Japan, it was felt that Japan is already heavily researched, but that there is relatively little easily available information on other, faster-growing East Asian economies. The scale and pace of change in these countries is unprecedented as technology transfer, globalization and liberalization have undammed their commercial energies. However, though the ‘Region’ exists as a geographical entity it is no more homogenous in national or business/organizational culture than is Europe. There are, for example, clear differences in industrial organization: the Chaebol of Korea and the Japanese sogoshosha differ in concept and management style and contrast with the networking of relatively small Taiwanese firms. The physical distance between Singapore and Tokyo is similar to that between Europe and the USA, but the cultural distance is probably considerably greater. Economic development also varies considerably among Asian countries: what these countries have in common is the ability to generate and cope with change at a rate outside contemporary experience elsewhere. A summary of the development status of the relevant countries is shown in Table 1.1 below.

Within Europe there are, of course, also wide differences between countries though within narrower geographic limits. The southern countries of the EU are less developed than the north, whilst the difference in development between the EU and the former Soviet Eastern European countries is even more marked. Because of these differences and because of liberalization, there are, within and between both these regions, considerable opportunities for trade and, particularly, investment. Whilst regionalism may have lessened internal trade barriers, it has also raised external ones. Trade barriers and frictions are likely to stimulate

Table 1.1 Economic development status among Asian countries

| Country | Development status | |

| NIE ‘Dragons’ | Singapore South Korea Taiwan Hong Kong | Developed* Mature NIE/Developed Mature NIE/Developed Mature NIE |

| ASEAN ‘Tigers’ | Thailand Indonesia Malaysia Philippines | Young/Mature NIE Developing Developing/Young NIE Young NIE |

| China | Young NIE | |

| Vietnam | Low income Developing | |

| Cambodia | Low income Developing | |

| Laos | Low income Developing | |

| Myanmar | Low income Developing |

*Singapore's official status as ‘developed’ is subject to some ambiguity. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) puts Singapore in the category of advanced developing nations no longer eligible for aid. However, its living standards are ahead of Britain.

Source: Adapted from Nomura Research Institute. Classification is based on current trade structure.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), an alternative to exporting, as a means of circumvention. Globalization and liberalization of firms and national economies, tied to emerging regionalism, have, in fact, provided the foundations for an enormous growth in FDI. Statistically, FDI figures are subject to varying degrees of over- or under-reporting, as well as to unpredictable innaccura-cies due to problems of reporting and data collection. However, the main trends and rough magnitudes seem incontestable. Between Asia and Europe, in both directions, and within Asia, this type of commercial activity is growing rapidly and at a much faster rate than conventional trade. Most of this book, therefore, is concerned with investment and direct linkages rather than with trade per se.

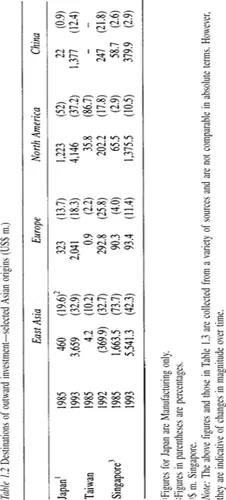

Much of the growth in Asian FDI has been driven by China's liberalization and opening-up to the outside world, particularly as a result of policies aimed at investment-led growth. Table 1.2 shows outward FDI figures for some of the main Asian investors. Between the mid-1980s and 1990s the total volume of outward investment increased by orders of magnitude. Absolute values of investment to the major destinations increased but the share of the US as a recipient declined in favour of the Asian countries, including China, and Europe. Only Singapore's pattern is different, arising from a very large decline in Malaysia's share of Singaporean FDI (from over 50% to less than 25% between 1985 and 1993). It is fairly clear that massive shifts in FDI can occur over relatively short periods of time. The boom in FDI into Europe in the early 1990s may have

Table 1.2 Destinations of outward investment-selected Asian origins (US$ m.)

Note: The above figures and those in Table 1.3 are collected from a variety of sources and are not comparable in absolute terms. However, they are indicative of changes in magnitude over time.

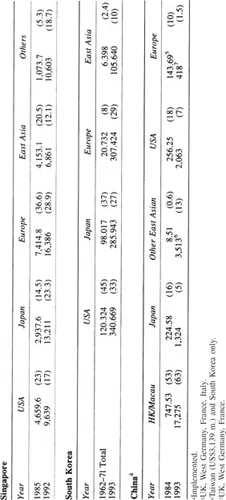

Table 1.3 Inward FDI in selected Asian destinations (US$ m.) (% share in brackets) (% share in brackets)

been induced by implementation of the Single Market and anticipatory fears of a Regional fortress. In the last two or three years there are indications of increasingly large switches into China despite Tiananmen.

Table 1.3 shows the magnitude and origins of FDI into Singapore, Korea and China. It shows clearly the massive increase in intra-regional FDI in less than a decade and, again, a decline in the US share. Both Table 1.2 and 1.3 confirm that there has been a significant increase in FDI, especially within the East Asia region, that Europe-East Asia investment is highly active in both directions and that this is growing.

Investment patterns are neither simple nor unidirectional. For example, between Hong Kong and China, capital is moving in both directions. Investment from Hong Kong to China is primarily in the traditional mature manufacturing sectors to take advantage of lower labour and land costs. Most of the manufacturing companies who have moved have closed their plants in Hong Kong. Increasingly, service firms are moving not only for cost advantage but also as support services following their mainly manufacturing clients. Investment from China to Hong Kong is primarily in the trade and financial services sectors: either to help emerging Chinese multinationals to engage with the world economy or to provide a backdoor for domestic capital to realize packages of benefits designed for foreign investors (sometimes known as round-trip investment). By far the greatest proportion of inward investment to China is from ‘overseas’ Chinese in Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, primarily a consequence of geographical and cultural proximity.

The complexity of FDI patterns reflects the different circumstances and objectives of firms. Analysts have identified a range of motivators, or determinants of FDI, none of which stands unique as a touchstone for understanding investment behaviour. Rather, the importance and relative ranking of these factors will vary from firm to firm, from time to time and from place to place. Most simply, in Porter's (1990) strategies in order to gain:

- Cost advantage. In this case firms seek to locate where production costs are low. Output may be exported, or re-exported in the case of semi-manufactures. Gaining cost advantage through relocation reinforces the product lifecycle view of FDI whereby firms transfer production to take advantage of growing demand in developing country markets for products which have matured in domestic and other developed markets. The process is seen on an accelerated scale within East Asia as firms move capital within the region and climb up the ‘development ladder': e.g. from Japan to the NIEs, from the NIEs to ASEAN countries, and from ASEAN to China, Vietnam, etc. This is known as flying geese investment.

- Differentiation advantage. Here companies seek access to specialist production factors, skill and expertise. Typically, this may be undertaken to facilitate technology transfer and is particularly likely to be accompanied by partnership or takeover arrangements with local firms. Examples include South Korean firms in Europe and even US firms in Taiwan (see Jocelyn Chen, chapter 4). In Singapore, government policy is active in encouraging centres of excellence, for example in silicon wafer technology, to attract incomers as well as to benefit domestic firms.

The actual decision to undertake FDI along the lines of the two generic strategies above may be precipitated by changes in socio-economic, political or legal conditions which can in turn be differentiated as ‘push’ or ‘pull’ factors. ‘Push’ factors typically describe increasingly adverse domestic conditions, such as tight labour markets (skill shortages, job-hopping and high wage costs), disadvantageous exchange rates, regulation and political instability. Economic ‘push’ factors are, especially in Asia, in business eyes often the unanticipated consequence of collective success. ‘Pull’ factors, conversely, result from increased attractiveness elsewhere. Examples are favourable changes in market proximity and growth, fiscal incentives, political risk, access to marketing channels, technology and information. Significant pull factors have emerged as a consequence of regionalization: firms try to realize the benefits of locating facilities within trading blocs rather than attempt to surmount ris...