eBook - ePub

Your Time Is Done Now

Slavery, Resistance, and Defeat: The Maroon Trials of Dominica (1813-1814)

Polly Pattullo

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 176 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Your Time Is Done Now

Slavery, Resistance, and Defeat: The Maroon Trials of Dominica (1813-1814)

Polly Pattullo

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Your Time Is Done Now tells the story of the Maroons (runaways slaves) of Dominica and their allies through the transcripts of trials held in 1813 and 1814 during the Second Maroon War. Using the evidence to explain how the Maroons waged war against slave society, the book reveals for the first time fascinating details about how Maroons survived in the forests and also about their relationship with the enslaved on the plantations. It also examines the key role of the British governor who succeeded in suppressing the Maroons and how the Colonial Office in London reacted to his punitive conduct. Read the evidence and hear the voices of the oppressed in resistance and defeat.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Your Time Is Done Now als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Your Time Is Done Now von Polly Pattullo im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Politics & International Relations & Politics. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

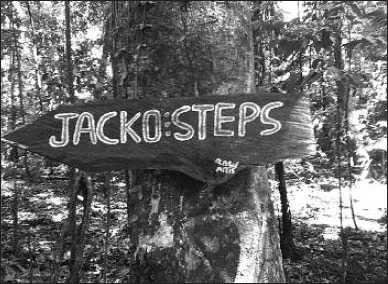

Steep and narrow, the Jacko Steps could only be approached by attackers slowly and in single file.

Now visitors are directed to them.

| 1814Up against martial law |

The Market House on the Bay Front, Roseau, where the courts martial of 1814 took place. It forms one boundary with the market place, the scene of executions.

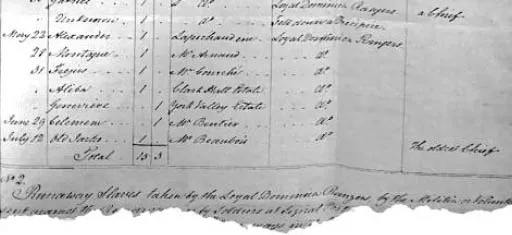

Recording Jacko’s death, 12 July 1814, with the comment, “the oldest chief”.

With Governor Ainslie’s declaration of martial law - the suspension of civilian rule - in January 1814 and the start of courts martial in the same month, his campaign to purge the Maroons intensified. Some of the courts martial were illegally constituted - as Lord Bathurst, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, later pointed out - but Ainslie appeared uninterested in due process.

The court martial was a military court, but, ironically, it was composed of civilian members of the local Militia drawn from the parishes. Militia members were not required to be trained in legal affairs but the Judge Advocate sat with them to advise on points of law. Those who featured as both judge and jury in the courts martial were in most cases planters and government officials; they were, as Lord Bathurst commented, not without their prejudices. The defendants had no legal representation and there was no jury.

The courts martial were held in the Market House on Roseau’s bay front, adjoining the market place (now known as the Old Market), rather than the Court House which had been destroyed in the hurricanes of the previous year. The Market House, built four years earlier in 1810, was the administrative centre for the activities of the market place where executions and slave auctions took place. Until recently, it housed the Dominica Museum.

Ainslie’s most effective weapon in his war against the Maroons was the newly formed Loyal Dominica Rangers, who consisted of “trusty” slaves, recruited through their owners. Paid, fed, armed and provided with uniforms, they were promised their freedom if they captured or killed a Maroon chief. The Rangers knew the forests and proved skilled in guerrilla warfare.

These trials of Maroons and their enslaved allies (four of the executed were not runaways but were charged with “harbouring and supplying runaways”) provide detailed information about both Maroon and plantation society. They are the raw material from which a much fuller picture of resistance and of life among the Neg Mawon might one day be conjured.

16 JANUARY 1814

Ainslie declared martial law on this day. In this letter to Bathurst, he defended this policy and his plan for raising a separate corps of Black troops - the Loyal Dominica Rangers - to pursue the Maroons.

I do myself the honour to acquaint your Lordship that I have judged proper to put this colony under martial law for one month from the 16th Instant. The runaway slaves who have been for 30 years established in the almost inaccessible mountains of Dominica, having become very troublesome from the depredations they were committing. I adopted this measure at the same time that I sent out parties from the Militia aided by a small force of Black troops. Some camps have been destroyed, a good number of the runaways have returned to their masters and I have little doubt, that at the expiration of the existence of martial law when, a colonial corps of Rangers now in training is to be posted to the principal camp, the colony will be comparatively freed from this evil. (CO 71/49)

Dominica’s Militia was distinct from the troops of the British army stationed in Dominica. Under the Militia Act, all free men between 16 and 50 had to serve in the Militia of their parish. The Militia operated as a kind of Home Guard to defend the rest of the population against slave uprisings. William Bremner did not hold the Militia in high regard. Here, he explains its limitations.

The Militia consisting chiefly of the managers and overseers of the plantations could be ill-spared for the superintendence of those concerns [on the estates], which suffered by their absence . . . Nor were they the sort of force likely to be able long to cope with such enemies, their habits and modes of life not being such as to render it probable they could long endure the excessive fatigue, numerous privations and constant exposure to the weather necessarily attending a service of this nature. (WB, p150)

In contrast, the Corps or Loyal Dominica Rangers served Ainslie’s needs well. Bremner described how the Rangers were led by Captain Savarin, a former army lieutenant, assisted by Sergeant Nash, a free black man who had performed a similar role in St Vincent.

[The Ranger Corps] was to embody a number of faithful slaves, and to put arms into their hands under proper officers. About 60 of these were speedily enrolled, accoutred, and clothed in an appropriate manner*: and rations and provisions were issued to them from the Government stores. The principal difficulty was to find a commander capable of the arduous task . . . All eyes were therefore turned to Mr Savarin who had several years before been employed with much success in a similar way, when a lieutenant in the army, but as he had quitted the service and had now a wife and a large family, and a property of his own to superintend, was doubtful whether he would now venture to undertake so laborious an occupation. He was however prevailed on by the Governor to accept the commission . . . he was most ably seconded in his exertions to train his recruits to the business, by a free Negro man named Nash, who was appointed Sergeant Major of the Corps, and who had lately arrived from St Vincent, in which colony he had been of essential use in a similar office . . . (*at the expense of the colony, who also undertook to pay the owners a stipulated hire per day, and rations etc) (WB, p152)

THE COURTS MARTIAL

15 January to 22 May 1814

With the declaration of martial law in Dominica, cases were heard by courts martial and not by the courts of special sessions. The courts martial, which sat on 11 occasions between January 15 and May 22 1814, heard the cases of 44 defendants. Twelve people were sentenced to death during the courts martial; 10 were executed in a period of four months (from January to May 1814). Six of the condemned were women: four were hanged, one called Rebecca was pardoned “at the gallows” and one, Hester, who was pregnant, died in jail. Two male defendants were found not guilty, two women discharged through ill-health and three women, including Rebecca, were pardoned.

Beyond the basic, documented facts surrounding each case, how accurate are the accounts of these courts martial? It is difficult to know. However, there is a clue in this letter from Benjamin Lucas, Commander in Chief of the colony after Governor Ainslie’s departure from Dominica, to Bathurst.

I have also been unable to get the minutes of the courts martial on the trials of runaway slaves copied to go by this packet. The Judge Advocate [WW Glanville] (who embarked for England last month) having written them in so careless a manner and on separate sheets of paper with contractions, erasures and interlineations, that the clerk I employed for the occasion can with difficulty read them. These, however, and the minutes of the special sessions, I shall also have the honour to transmit by the next packet. (CO 71/50)

In addition to Lucas’ claims that the minutes had been carelessly written, one might also speculate whether some evidence was omitted, either intentionally or by mistake. Adding to these ambiguities is the fact that some of the evidence is in reported speech rather than direct speech, thus rendering it less immediate and possibly less accurate.

However compromised, the evidence, especially that in direct speech, is revealing. It is unusual - in the history of slavery in the Caribbean - to hear the voices of the enslaved. Despite official apathy, antipathy, inefficiency, bureaucracy, inertia and so on, these voices survive, and we hear their words as defendants, as witnesses and as the members of the Loyal Dominica Rangers.

However we interpret this material, these accounts further our understanding of the relationships between the e...