eBook - ePub

Fluorescent Imaging

N. Kokudo, T. Ishizawa

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 132 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Fluorescent Imaging

N. Kokudo, T. Ishizawa

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence has been used for imaging purposes for more than half a century; First employed by ophthalmologists for visualizing the retinal artery in the late 1960s, the application of ICG fluorescence imaging has since been continuously expanded. Recently, advances in imaging technologies have led to renewed attention regarding the use of ICG in the field of hepatobiliary surgery, as a new tool for visualizing the biliary tree and liver tumors.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Fluorescent Imaging als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Fluorescent Imaging von N. Kokudo, T. Ishizawa im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Medicine & Gastroenterology & Hepatology. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Thema

MedicineClinical Applications of Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Imaging

Kokudo N, Ishizawa T (eds): Fluorescent Imaging: Treatment of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Diseases.

Front Gastrointest Res. Basel, Karger, 2013, vol 31, pp 10-17 (DOI: 10.1159/000348601)

Front Gastrointest Res. Basel, Karger, 2013, vol 31, pp 10-17 (DOI: 10.1159/000348601)

______________________

Identification of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Takeaki Ishizawa · Norihiro Kokudo

Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery Division, Department of Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

______________________

Abstract

Fluorescence imaging using indocyanine green (ICG) enables highly sensitive identification of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) by allowing visualization of impaired biliary excretion of ICG in differentiated HCC tissues and/or in noncancerous liver parenchyma around the tumor. In this technique, ICG is administered intravenously at the dose of 0.5 mg/kg for routine liver function testing within 2 weeks prior to surgery. Intraoperatively, liver cancer can be easily identified by fluorescence imaging of the liver surface prior to resection and on the resected specimen. Intraoperative ICG fluorescence imaging is useful for detecting superficially located small HCCs and confirming that these lesions have been removed with sufficient surgical margins. The present technique also enables identification of new lesions of HCC that have not been diagnosed preoperatively; however, additional resection should be considered only after re-evaluation by visual inspection and palpation or intraoperative ultrasonography because the positive predictive values of such newly detected lesions are 50% or lower, especially when the ICG is administered on the day before the surgery in patients with liver cirrhosis.

Copyright © 2013 S. Karger AG, Basel

In 2007, we developed a fluorescence imaging technique for intraoperative cholangiography using intrabiliary injection of indocyanine green (ICG) [1]. While developing this technique, we noticed that cancerous tissues on the liver surface emitted their own fluorescence even before the intraoperative administration of ICG for cholangiography. Actually, in all the patients at our department, ICG is administered intravenously before surgery in order to measure the ICG retention rate at 15 min as a routine liver function test. Thus, it was assumed that the intraoperative visualization of liver cancer by ICG fluorescence imaging was caused by accumulation of the ICG injected intravenously prior to the surgery in cancerous tissues and/or surrounding noncancerous liver tissues at the time of surgery. Then, a prospective clinical study was initiated to evaluate the efficacy of fluorescence imaging utilizing preoperatively injected ICG to detect liver cancer during surgery [2]. Here, we focus on the mechanistic background and clinical applications of intraoperative ICG fluorescence imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Other chapters in this volume detail the use of the ICG fluorescence imaging technique for the identification of metastatic liver cancer during surgery.

Principle of Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Imaging of Hepatocellular Cancer

Fluorescence imaging of liver cancer using preoperative intravenous administration of ICG is based on the fact that ICG is exclusively excreted into the bile and emits fluorescence that peaks at about 840 nm when protein-bound ICG is exposed to an excitation light in the range of 750-810 nm [3]. Because visualization at this wavelength is scarcely affected due to absorption by hemoglobin or water, biological structures that contain ICG can be visualized through tissue thicknesses of 5-10 mm with the use of an appropriate filter and a camera that is sensitive in the infrared region. On the other hand, a certain pathological type of HCC, termed ‘green hepatoma’, is known to retain the ability to produce bile. Furthermore, previous studies of delayed magnetic resonance imaging obtained 10-24 h after the administration of a contrast material excreted via bile suggested the presence of impaired bile excretion in HCC tissues as well as in noncancerous liver parenchyma surrounding the tumor, resulting in hyperenhancement of well-differentiated HCCs and rim enhancement of metastatic liver cancer [4-7]. Based on the above findings, we developed an intraoperative ICG fluorescence imaging technique aimed at visualizing liver cancer on the liver surface during surgery or on resected specimens based on the impaired biliary excretion in HCC tissues and in the noncancerous liver parenchyma around the tumor [2].

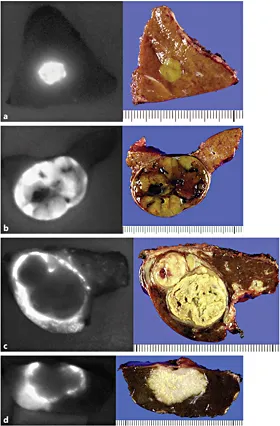

In our previous series consisting of 37 patients with HCC and 12 patients with colorectal liver metastasis, fluorescence imaging following preoperative intravenous administration of ICG at the dose of 0.5 mg/kg identified all of the microscopically confirmed HCCs (n = 63) and colorectal liver metastases (n = 28) on the cut surfaces of the resected specimens. The fluorescence patterns of these tumors were classifiable into the total fluorescence type (all of the cancer tissues showed uniform fluorescence), partial fluorescence type (a part of the cancer tissues showed fluorescence) and rim fluorescence type (the cancer tissues were negative for fluorescence, but the surrounding liver parenchyma showed fluorescence; fig. 1) [2, 8]. The fluorescence patterns were closely associated with the characteristics of the liver cancers: the total fluores-cence-type tumors included all of the well-differentiated HCCs, while the rim fluorescence-type tumors consisted of only poorly differentiated HCCs and colorectal liver metastases. Furthermore, fluorescence microscopy confirmed the presence of fluorescence in the cytoplasm and pseudoglands of the HCC cells and in the noncancerous liver parenchyma surrounding the poorly differentiated HCCs and metastases (fig. 2).

These results are consistent with the previously proposed mechanism of ICG accumulation in cancerous tissues and/or noncancerous liver parenchyma around the tumor. Such pharmacokinetics of ICG in the liver involving HCC may be proven by gene expression analysis and immunohistochemical staining, as used in the previous study conducted to reveal the background of magnetic resonance imaging of HCC with gadolinium ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid [9]. Our preliminary results suggested that the expression levels of portal uptake transporters of ICG (organic anion-transporting polypeptides and Na+/taurocholate cotransporting poly-peptide [10]) are well-preserved in HCCs showing fluorescence of ICG in the cancerous tissues as compared with the impaired gene expression levels in the cancerous tissues of rim fluorescence-type HCCs (unpubl. data).

Fig. 1. Fluorescence patterns of liver cancers on cut surfaces of the liver (left) and their gross appearances (right) [8]. a Total fluorescence type (well-differentiated HCC, 7 mm in diameter). b Partial fluorescence type (moderately differentiated HCC, 35 mm in diameter). c Rim fluorescence type (poorly differentiated HCC, 30 mm in diameter). d Rim fluorescence type (metastasis of colorectal cancer, 25 mm in diameter).

Fig. 2. Fluorescence microscopy. Fluorescence microscopy reveals that fluorescence of ICG (indicated in green) exists in cancerous tissues of well-differentiated HCC (a) and in noncancerous liver parenchyma around the tumor in poorly differentiated HCC (b).

Actually, the fluorescence imaging technique using ICG to identify liver cancer was included in a patent obtained by a group at the University of Rochester (WO 2008/043101 A2). Although there have been no detailed articles concerning liver cancer imaging, except for a recent article on ICG fluorescence imaging of renal cancer [11], their method is probably not based on the disordered biliary excretion of ICG, but on the difference in hemodynamics between cancerous tissues and noncancerous liver parenchyma that may occur in the earlier phase after intravenous administration of ICG.

Advantages and Limitations of the Use of Indocyanine Green

The major advantage of ICG fluorescence imaging is its sensitivity and feasibility: once the ICG retention test has been performed within 2 weeks prior to the surgery, surgeons can obtain fluorescence images of the liver cancer with a commercially available small imaging system at any time during the surgical procedures in order to detect cancerous tissues on the liver surface before resection or on the resected liver specimens. Although the ICG retention rate at 15 min has not been widely used as a preoperative liver function test in Western countries, this test is practically the only way to estimate the acceptable limit of liver volume to be removed in each patient [12]. Especially in liver resection for patients with background liver disease, it is strongly recommended that the ICG retention rate at 15 min be evaluated not only for intraoperative ICG fluorescence imaging of liver cancer, but also to ensure the safety of liver resection [13].

In contrast, it should be noted that when 0.5 mg/kg of ICG is administered intravenously for a liver function test on the day before surgery, washout from the noncancerous liver parenchyma is inadequate and there may be many false-positive nodules; the poorer the liver function, the more marked this tendency [2]. Further studies are needed to determine the optimal interval between ICG injection and surgery on the basis of the patient's liver function. Moreover, this technique does not use a cancer-specific antigen-antibody reaction. Instead, it just allows visualization of the impaired bile excretion in HCC tissues and/or noncancerous liver tissues around the tumor. Thus, benign lesions, such as regenerating nodules, bile duct proliferation and expanding liver cysts, may also exhibit fluorescence if there is delayed bile excretion. In fact, in previous reports, 40-50% of the lesions newly identified by fluorescence imaging during surgery were pathologically proven to be noncancerous lesions [2, 14, 15]. Even when new lesions are detected by ICG fluorescence imaging during surgery, additional resection should be considered only after the lesions have also been confirmed to be cancerous by inspection and palpation, and/or by an intraoperative ultrasonography.

Clinical Application of Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Imaging

Considering the advantages and limitations of ICG fluorescence imaging for liver cancer, its major expected roles in liver resection for HCC are to identify: (1) peripherally located, but invisible HCC diagnosed preoperatively, (2) new lesions to be considered for additional resection, (3) HCC tissues left on the raw surface of the liver after resection, and (4) small HCCs on the resected specimens.

In liver resection for HCC, especially during repeated resection for rec...