eBook - ePub

Brewing

Ian Hornsey

This is a test

Buch teilen

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Brewing

Ian Hornsey

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

It is believed that beer has been produced, in some form, for thousands of years - the ancient Egyptians being one civilization with a knowledge of the fermentation process. Beer production has seen many changes over the centuries, and Brewing, Second Edition brings the reader right up to date with the advances in the last decade. Covering the various stages of beer production, reference is also made to microbiology within the brewery and some pointers to research on the topic are given.

Written by a recently retired brewer, this book will appeal to all beer-lovers, but particularly those within the industry who wish to understand the processes, and will be relevant to students of food or biological sciences.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Brewing als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Brewing von Ian Hornsey im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Technology & Engineering & Food Science. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Historical Material

“What’s in a name?” For the purposes of this book, the term “beer” equates to that product described by Max Nelson1 as “a fermented drink made essentially from malted cereal, water, and yeast”.

Thus, in its broadest sense the word “brewing” may be defined as “The combined processes preparing beverages from the infusion of sound grains that have undergone sprouting, and the subsequent fermentation of the sugary solution (wort) produced by yeast – whereby a proportion of the carbohydrate is converted to ethanol and carbon dioxide”. The modern connotation of the word would imply “production of beer”, in all its various forms – and this is how the author has interpreted it.

From the definition above it can be inferred that any unspoiled grain can be employed provided that the seed has sufficient polysaccharide food-reserve (endosperm). A cereal grain, or, more accurately, the unique seed-like fruit (caryopsis) produced by members of the grass family (Poaceae), when raw presents a relatively unattractive foodstuff and so a combination of soaking in water, or milling and mixing with water, will render products that are far more palatable. These, initially crude, processes have undoubtedly provided the basis for the malting, brewing and baking industries that we know today. Some extant beer types, chicha2 is an example, can be made from grains and/or from other plant material – in this case cassava roots, and it is evident that in ancient times a huge range of plant material was used to prepare “beers”. For a variety of reasons, barley has evolved to become the grain of choice for the brewer, whilst wheat is preferred by the baker. The histories of beer and bread are intertwined, and some authorities have eloquently made the case for beer being considered as “liquid bread”.3,4

1.1 LIKELY ORIGINS OF BREWING

With the brewing industry now being dominated by a few multinational companies, it is difficult to envisage that, for most of its history, brewing was a domestic, or at best a small-scale commercial enterprise, scarcely removed from its agrarian roots. Enough scientific and archaeological evidence now exists5,6 for us to believe (although there are dissenters, mainly due to the absence of clear archaeological evidence7) that what we know as “European-style beer” was first produced in the late fourth millennium BC by the Sumerians in southern Babylonia. The Sumerian civilisation was situated in Lower Mesopotamia – in the alluvial plain between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates – and it was one of the earliest literate civilisations known. Situated in the Fertile Crescent, one of the world's most important centres of cultural development, this region is one of the centres of early agriculture.8 The world's oldest recipe, written on Sumerian clay tablets, is for the making of beer; for the Sumerians were known to be great beer drinkers. Another early tablet consists of a hymn to the beer goddess, Ninkasi, whose very name means “the lady who fills the mouth”. According to Civil,9 “Ninkasi was brewer to the Gods themselves”, she who “bakes with lofty shovel the sprouted barley”, who “mixes the bappir-malt with sweet aromatics”, who “pours the fragrant beer in the lahtan-vessel, which is like the Tigris and Euphrates joined”.

One school of thought attributes the transformation of Man from nomadic hunter-gatherers, to sedentary, crop-growing peoples, to the accidental discovery of the physiologically interesting beverages that resulted from fermented moist wheat and barley. The theory, championed by Dr Solomon Katz10 of the University of Pennsylvania, propounds that the “mood-altering” and nutritional properties of these new beverages provided the motivation for a primitive form of agriculture that would have given the populations indulging in it a less strenuous way of life. Dr Katz goes on to propose that the initial discovery of a stable way to produce alcohol provided the stimulus for people to collect different seeds, to cultivate them and try to improve crop characters.

It soon became obvious that air was detrimental to these fermented brews and, thus, one saw the development of narrow-necked storage vessels common in archaeological sites in Mesopotamia. Such vessels, it is surmised, were designed to keep bad gases (air) out and good gasses (carbon dioxide) in.

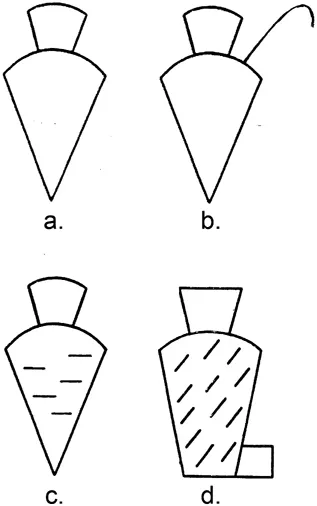

One of the most thoroughly investigated sites is at Godin Tepe in the Zagros mountains of what is now Iran. There is evidence that the neighbouring Sumerians exploited this area for some of their essential commodities – and brought their beer-making knowledge with them. There were numerous examples of carbonised six-rowed barley excavated together with fragments of pottery jars with unique criss-cross grooving on the inner surfaces. It is thought that these grooves were designed to retain the sediment from the beer after storage. Chemical analysis of sediment found in the grooves indicated the presence of calcium oxalate,11 a principal (insoluble) component of “beer-stone”. As the modern brewer knows well, beer-stone is an inorganic, scale-like, deposit that accumulates in fermentation vessels and beer storage tanks. Oxalic acid is present in trace amounts in malt, and combines during the mashing stage with calcium ions to form the insoluble salt. Ancient jars known to have contained wine, cider and mead do not show any evidence of calcium oxalate deposits. The pattern of grooving on the inner surface of the jar fragments bears great resemblance to the Sumerian signs for beer, called kaš (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Early Sumerian signs for ‘beer’.

An extensive collaborative study between University of Cambridge archaeologists and, the then, Scottish and Newcastle Brewery, under the auspices of the Egypt Exploration Society, has produced an insight into how the ancient Egyptians carried out their fermentation technology 3000 years ago. Studies concentrated on two sites on the River Nile: Armana (some 200 miles south of Cairo) and Deir el-Medina; both sites dating to the period known as the New Kingdom (1550–1070BC). Because these sites are outside of the flood-zone of the Nile, the arid climate has allowed desiccated botanical and other biological remains to persist until the present day.

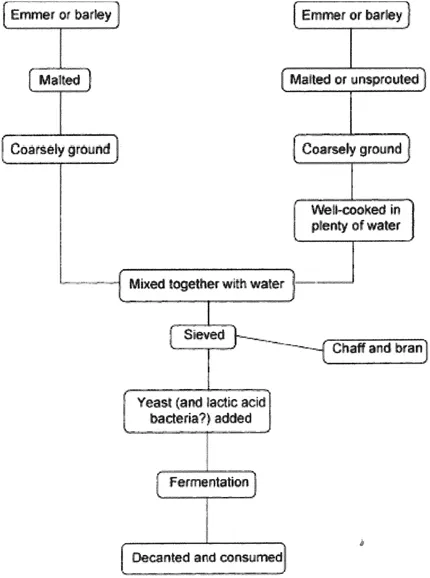

Beer and bread were the most important dietary items of the ancient Egyptians; as evidenced by the plethora of written records concerning the production and consumption of these products. Beer was used as currency at this time, and everyone, from the Pharaoh downwards, drank it. No meal was complete without it and it played a key role in ritual and religious practice, as the number of brewing-related illustrations on the walls of tombs will testify. It has even been suggested that the pyramids were built on a diet of bread and beer! A wide variety of beer types are documented from this period.12 What are the differences? It is likely that varying categories of beer served the needs of different classes in the population. Archaeological evidence shows that barley was certainly used for brewing, and so was emmer wheat, which was the dominant cultivated crop throughout much of the Old World. The two grains were, in some products, used in conjunction, which could partly explain the variety of beers produced. Some ancient beer residues have been analysed.13

With the aid of scanning electron microscopy, Samuel14 has demonstrated that some grains were sprouted (malted!) before being crushed and used for brewing; the starch grains from such recovered samples showing the characteristic pitting caused by enzymic attack. Unsprouted grains were also used and these appeared to be cooked in hot water before being fermented. There was also evidence of roasted grains being used, presumably to impart colour and flavour to the product. The abundance of lactobacilli from certain brewing sites indicates that these organisms were involved in fermentation as well as yeasts – just as they are today in certain beer styles. Brewing and baking in ancient Egypt has been thoroughly studied by Samuel.15

As a result of the direct evidence obtained from the area, Samuel proposed a model for New Kingdom brewing (Figure 1.2). Some of the earliest fermented products in Egypt were very thick in consistency and were called “boozah”,16 whilst later, slightly more refined, beverages were known as “hekt”.

Figure 1.2 Model for New Kingdom ancient Egyptian brewing (Courtesy of Dr Delwen Samuel).

The sites around Armana are believed to be within the boundaries of the lost Sun Temple of Nefertiti (i.e. these were Tutankhamun's breweries), and in 1996 the then Scottish and Newcastle Breweries, using Samuel's brewing model, re-created this ancient style of beer. Specially grown emmer wheat was malted for the project, which resulted in a highly distinctive bottled beer called Tutankhamun Ale.

Brewing flourished in Egypt until the end of the 8th century AD when Moslem Arabs conquered the region (the Koran forbids the making, sale and drinking of alcoholic beverages), but the art of brewing had spread far beyond the confines of the Middle East; traders to and from the region gleaned the essentials of beer-making and thus the techniques were disseminated. It is to be assumed that it was via traders that the beer culture reached the British Isles. Certainly, the Romans found beer to be in production here when Julius Caesar invaded in 55 BC. They also found that there were cereal crops under cultivation in certain areas, again emphasising the importance of the sedentary way of life in the gradual civilisation of mankind. At that time, however, mead and cider seemed, according to Roman records, to be far more prevalent beverages in Britain, and wine was widely drunk in mainland Europe. Recent work suggests that drinking beer may have been a far more long-standing tradition in parts of the Roman Empire that was previously thought.17

The word “beer” was thought, by some authorities, to be derived from the ancient English word “beor”, which meant “inferior mead”, but this is probably not the case.5 There is now much conjecture as to the origin and relationship between the terms “beer” and “ale”, and so I shall keep my powder dry at this juncture.

Records are scarce from the Dark Ages, but from what we know about mediaeval times, brewing was more or less confined to monasteries, both in the British Isles and continental Europe.18 By the 13th century there were hundreds of monastic breweries in northern Europe, each supplying the local community with its wares, and this was a convenient way of raising funds for ultimately more saintly purposes! A few of these monastic brewing sites still exist today in Belgium and the Netherlands. Within these religious communities considerable attention was given to improving the quality of the end-product. Many of our present-day beer styles originated from these times. For example, Bavarian brewing monks not...