![]()

PART I: THE FRAMES OF SUBSISTENCE: COSMOLOGY, ETHNOGRAPHY, HISTORY

![]()

1Hunger in Relief

Village Life and Livelihood

All the rocks in Singida were once meat. People were eating them all the time. But they were also given the law by the elders that they should never put salt on the meat. One day, a person decided to put salt on the meat, even though he had been told many times not to. He didn’t believe it. He thought that he was doing a good thing, but kumbe!, he broke the command. On that day, all the meat turned to rocks, and there was not so much to eat.

The Story of How all the Rocks in Singida Were Once Meat. Told by Mama Rosalia, 2005

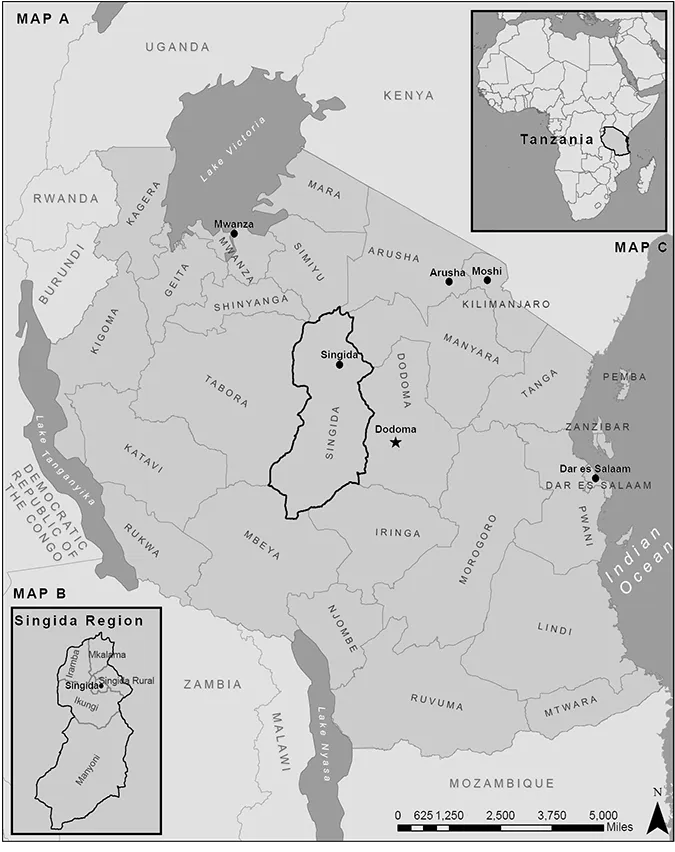

LET US BEGIN then with the social and material landscape of Singida region. Singida region, home to over a million residents, sprawls in Tanzania’s heartland, 700 kilometers northwest of Tanzania’s commercial center, Dar es Salaam, and 330 kilometers northwest of the nation’s capital Dodoma (see map 1.1). Three of Singida’s six administrative units—Singida Town, Singida Rural District, and Ikungi district—constitute Urimi, the land of the Nyaturu—an ethnic group also known as the “Turu” or “Rimi.” Singida Town is the administrative and trading nucleus of the region, and draws workers and professionals from the other districts of Singida. Like most of urban Tanzania, Singida Town has become a lively Swahili market town of many tongues, with migrants from northwestern Tanzania, Swahili traders from the coast, and a few Asian, Omani, and Somali families running many of the interregional food and clothing trade, bus companies, restaurants, and internet cafes.

Singida Town is a crossroads, marking the intersection of recently paved inter-city routes to Dodoma, Arusha, and Mwanza. It boasts a regional hospital, several private clinics and banks, a post office, a plethora of mosques and churches, a bus stand and a range of guesthouses and eating establishments that serve both local patrons and the many traders and truckers who pass through town. But just outside the small grid of dirt alleys that surround the intersection of these tarmacked roads, the land of the Nyaturu begins, stretching out into a thick ring around Singida Town.1 The peri-urban villages of Singida Municipality graduate into the increasingly rural villages of Singida Rural District and Ikungi District, which are home to three loosely defined Nyaturu language sub-groups: the Wahi (to the south and west); the Wirwana (to the north) and the WaNyamunging’anyi (to the east).

Boarding a daladala mini-bus in Singida Town, one can journey out the Arusha road, past a rundown government secondary school and through the grand natural gates formed by two large boulders emblazoned with painted condom and laundry detergent advertisements. The road is lined with modern houses of cement brick and corrugated iron roofs, small shops with signs sponsored by soda and beer companies, and a fancy new hoteli serving grilled meat and beer. As the mini-bus climbs out of the large valley that houses Singida Town and its two large salt-water lakes, Singidani and Kindai, the bus ascends to what will eventually drop dramatically into the escarpment of the Great Rift Valley and—beyond Singida’s borders—to the foothills of Mount Hanang. Evidence of electrical wiring has vanished.

The landscape is alternately monotonous and majestic, with broad expanses of barren brown (in the dry season) or bright green (in the short rainy months) farmland interrupted by thickets of thorny brush and striking rock outcroppings upon which cellular phone antennas or water tanks may perch. As the bus climbs, modern houses become fewer and further between and in their stead one sees the nyumba za kienyeji (traditional houses) of the Nyaturu—the low long rectangular mud-brick structures with grass and mud roofs (see plate 2).

About ten kilometers out of town the bus reaches a crossroads from which one can glimpse a spectacular view of the escarpment and Great Rift Valley below, and the intersection of the borders of four villages. The intersection hosts a festive weekly livestock, food, and clothing market (see plate 3) and a more permanent settlement of small shops, beer clubs, and a small mosque. The grid of intersecting roads offers vehicle routes to surprisingly distinct eco-systems and linguistic and social environments in Singida. And between these roads lie an intricate network of cattle and human footpaths that carve their way through farms, forests and thornbrush. These paths circumvent the rock outcroppings to connect village centers and the hundreds of interior sub-villages (vitongoji, or hamlets) to transportation networks, medical facilities, schools, water sources, and each other.

The villages, even in this small corner of Singida, are each distinct from one another. There are villages that lie along the road, and so have already “received a bit of the light of development,” and villages that lie “inside” well beyond the networks of public transportation. There are peri-urban villages (those lying within the boundaries of the Municipality) and rural villages (those located in Singida Rural District). In addition some villages have “given birth to” (vimezaa) other villages, as in the case of the village I call “Suna”—a village whose mission-constructed school served an area that has since been divided into four villages that now have primary schools of their own. Suna village is the “the elder” (mzee) of its offspring which, its residents assert, has mixed implications. Suna is the seat of the ward (four-village) government, the first of the four villages to get electricity, the site of a mission secondary school, and since 2007, the site of a government secondary school constructed for the four villages. Yet many in Suna consider their village as much kikongwe (a term also used for the elderly but with the connotation of infirmity) as mzee (the respected elder). Their school buildings are dilapidated and the village government is perceived to be entrenched and ineffective in contrast with its offspring “Langilanga” village’s youthful energy and motivated leadership. These distinctions between villages have material implications. “Elder” Suna is seen to be the proper center for continuing development for the ward (the new secondary school should be where there is electricity, where its teachers may find housing); but youthful Langilanga, whose citizens are much less burnt out on their government, has received more opportunities for participatory pilot projects. The two interior villages of the ward receive food aid well in advance of Suna and Langilanga, whose residents—living along the road—are presumed to have better access to other forms of assistance, mobility, and support.

In contrast to the perceptions of many urban Tanzanians, tourists, and members of the foreign aid establishment, kijijini (the space of the village) as lived by the people of Singida, is a vastly differentiated space. Within a village, people compare spaces of good farmland and bad, heavy and poor rains, wildlife habitats and people habitats, madukani (“the shops”) and mbugani (“the grasslands”), barabarani (“on the road) and bondeni (“in the valley”), kin settlements and road settlements, Lutheran, Muslim, and Roman Catholic hamlets, and places where amenities like wells, shops, transport possibilities, the school, church, and drinking clubs may be found reasonably nearby, and, alternately, places in which there is a lack thereof. In spite of these clear oppositions, not everyone experiences these spaces in the same way. For as Ching and Creed note, “almost any inhabited place can be experienced as either rural or urban” (1997, 13). A daughter-in-law from Arusha city in northern Tanzania who visits her husband’s family in their homestead near the shops of the Singida roadside village of Langilanga, struggles with the drudgery of “the life of the village” (maisha ya kjijini). Meanwhile the head teacher’s wife who has married there from a more isolated area is still acclimating to the exciting business opportunities (she brews beer) but the loose morals of “life on the road,” where drinkers from outlying homesteads and hamlets gather to mingle and flirt.

And yet there are experiences and perspectives that connect rural populations in Singida unrelated to whether people are rich or poor, roadside or inside, central or marginal to Singida’s social and economic life. The pulse of the annual cycle’s wet and dry seasons drives an agricultural, social, political and economic calendar that, regardless of one’s relative socioeconomic position, oxygenates rural lives and infuses the shared air that they breathe. To better grasp these situated and yet inextricably connected perspectives of village life, let us meet one extended family in rural Singida.

NyaConstantino’s House

NyaConstantino, “the mother of Constantino,” is squat and strong, though she is small and now in her sixties. She lives down in one of the deep dips along the escarpment that lead to the steep drop into the Rift Valley. The round face that she shares with her younger son, Petro, bears all the features of a good gossip, with expressions that shift quickly from shrewd assessment, to dramatic pause, to warm raucous laughter. My first visit to her home, it seemed, was good cause for all three, though she soon settled into the latter, for like the Nyaturu saying goes, “strangers are sent by the sun.”

The language she speaks is the language of the elder women—the last and least of the Nyaturu to be “nationalized,” to use the Tanzanian political parlance. Her words—a loose hybrid of Swahili vocabulary plugged into a river of Nyaturu words—flowed over me as I, still in my early months in Singida, tried in vain to isolate and identify them. She was equally mystified by my own Swahili, with its foreign cadence, coastal constructions, formal grammar, and absence of Nyaturu-isms, which I would eventually incorporate into my own speech. In future meetings I was often accompanied by a friend and research assistant who could bridge lingering linguistic gaps. But in this first chance encounter, we—as people are bound to—just made do.

Her children have estimated that NyaConstantino was born sometime around 1940. She herself doesn’t know the year, she explains, because there was little opportunity at the time for girls to study, and little interest among their parents to educate them. There was much work to do at home in these farming and herding communities, and girls like NyaConstantino married young and left to join their husbands’ families.

By the 1940s Evangelical Lutheran missionaries from the midwestern United States and European Roman Catholic missionaries had carved out separate zones of influence in rural Singida with the intent of converting Singidans and stemming the tide of Islam. NyaConstantino’s parents converted to Christianity and from her early childhood she attended the tiny Lutheran Church in her natal village, which lay on the main road from Dodoma to Singida, approximately 15 kilometers from Langilanga. She would not live there many years. As was common in the 1950s, she married before she had begun to menstruate. She moved to the forests of the valley hamlet in Langilanga (see plate 4) to join her husband’s family, but in accordance with custom, returned home for ritual instruction at several points in her life and maintained strong bonds, especially with her mother and brothers.

NyaConstantino gave birth to seven children, of which four are still living. Her husband died more than ten years ago, and she now enjoys the status of mukhikuu (Ny.), an elder woman whose sons have married and settled on lineage lands and whose wives now help her and defer to her as they manage their family affairs. Anthropologist Harold Schneider, who lived among the Nyaturu from 1959 to 1960, noted that “the ultimate position of success for a woman is to have sons and be head of a rich house, or even a homestead, after her husband dies, so that it is unnecessary for her to be inherited by a brother of her dead husband. In this status she has the greatest amount of freedom available to a woman” (1970, 126). Times have changed over the last five decades: religious and state authorities provide some protection against wife inheritance where it is not wanted. But now homesteads are evaluated less by their riches than by their ability to withstand crisis (the social security of cattle having long since collapsed). Moreover, able-bodied sons and daughters increasingly migrate away from the infirm to the promise and prestige of the cities. The concern of the old women of villages is less a question of freedom than one of potential neglect. Who shall cook and farm for me, when my strength fails? Who shall pay for me to see a doctor, when I am ill? Who shall fix my roof, when the rains come? And who shall feed me, when food is scarce? Indeed, the few extreme cases of adult starvation in Singida that lead to fatality are in nearly every case elderly women who have been socially stranded by widowhood and real or functional childlessness (cf. Cliggett 2005).

As is customary, NyaConstantino shares her original homestead with her youngest son Petro and his tall, angular wife, NyaLukas. NyaConstantino’s eldest child, Constantino, lives in a neighboring homestead with his own wife and five children. With two grown sons “at home” who have wives and sons of their own, NyaConstantino will be looked after in her old age, so long as her sons’ households continue to thrive. Both her well-being and her precarity are securely hitched to theirs.

NyaConstantino finds social protection not only in her children but also in her local role as midwife for the hamlet. Prior to independence, her husband had been a doctor in a local clinic and taught her how to deliver babies, since trained nurses were too few. Over the last five decades she has delivered many babies in her hamlet, and while unpaid for this work, she is “remembered” (i.e., provided with material assistance) when times are difficult for her.

NyaConstantino is most animated when surrounded by her age-mates, passing the deep plastic cup of thick lukewarm sorghum beer that locals call the chai ya wazee (the “tea” or “breakfast” of the elders). Such occasions take place weekly in the dry and early wet season when her daughter-in-law hosts a beer party to convert some of her harvest into cash, and more often when other young women in the hamlet brew and host. The drinkers, young and old, gather in mid-morning after a first round of cultivation or other seasonal work. Some return home to work further, others loiter—singing, celebrating, flirting. Such behavior among young people is frowned on though the Catholic Church has proven more tolerant than the Lutherans, Muslims, and Pentecostal Christians. Even NyaConstantino and the elder peers with whom she shares a cup lament drunkenness among young people, who have not yet earned their right to beer through a lifetime of hard work. But as an “old woman of the old ways,” e...