![]()

PART I

CITY-COSMOS

IMAGINED

![]()

ONE

URBAN MAPPINGS

FROM THE HEAVENLY TO THE EARTHLY CITY

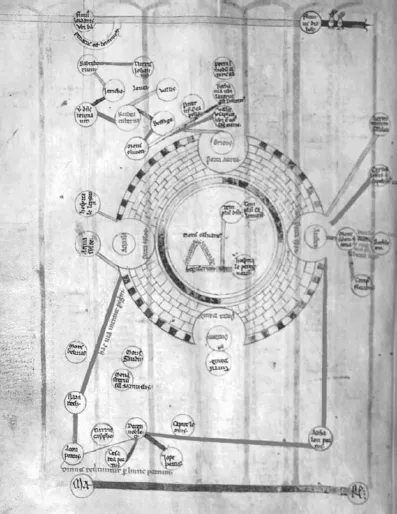

The city that lay at the heart of the medieval world – the axis mundi – was of course Jerusalem. ‘The city of Jerusalem I have set among the nations’, Ezekiel proclaims, ‘with the other countries round about her.’1 Just as the round earth was at the centre of a circular Christian cosmos, so the city of Jerusalem was the symbolic centre of the world.2 The Psalter map, for example, shows Jerusalem as a round red spot encompassed by two concentric rings (illus. 36).3 This particular form is also used in more detailed visual representations of the city, which typically depict it as a circle of walls. This idealized form of Jerusalem was, in Ousterhout’s words, a ‘flexible geography and transportable topography’,4 in which the holy city was presented as an archetype, an imagined vision of what the city looked like, rather than how it actually was. To this end, the circular-shaped Jerusalem not only symbolized a wider cosmos, of which it was the sacred and spiritual centre, but it also provided a model on which to fix images of other cities. Jerusalem’s idealized geometrical form became the basis for depicting cities all over the medieval Christian world.

Heavenly Jerusalem, the celestial city, is described in Revelation descending down from heaven: ‘and I John saw the holy city, New Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for a husband.’5 The city’s richness is conveyed in colourful, beautifully drawn images that illustrate the many medieval manuscripts relating the story of the Apocalypse, an imagery that emerged in the fourth century and gained in popularity through the Middle Ages, particularly the Carolingian period, but also later on in the thirteenth century.6 In all these images the Heavenly Jerusalem is depicted slightly differently in its details. Sometimes it is populated with buildings and turrets, as with examples in the Trier and Cambrai manuscripts of the ninth century (illus. 37); sometimes it is simply a space enclosed by walls devoid of detail except for Christ, signified usually either as the Lamb of God or the Tree of Life positioned at its centre, as shown in the Trier, Cambrai and Valenciennes manuscripts (illus. 38).7 Sometimes the city is shown in elevation, as a bird’s-eye view, and sometimes projected as a plan, ‘laid flat’.8

The Biblical description of the heavenly Jerusalem makes clear what shape the celestial city should be: ‘the city lieth four-square, and the length is as large as the breadth’, with ‘on the east three gates; on the north three gates, on the south three gates; and on the west three gates.’9 Such a square-shaped city is depicted in the thirteenth-century Trinity Apocalypse manuscript, and the earlier Paris Bibliothèque Nationale manuscript 2290, but in Carolingian drawings of the ninth century the heavenly city is invariably presented as circular in form, a circle of walls, as indeed it is in some later sources, such as the ‘Trinity Apocalypse’ and Lambert of Saint-Omer’s Liber floridus (illus. 39 and 40).10 Depictions of a circular-shaped celestial Jerusalem are clearly at odds with the city’s square form described by scripture. The reason for using a circle seems to lie in the cosmological significance of its geometrical form, coupled with the central place of Jerusalem in the Christian world.11

There was an imagined symmetry between the shape of Jerusalem and the shape of the world, as Ousterhout has noted: ‘the same schema that underlies the medieval world maps defines the plan of Jerusalem – an “O” forming the walls of the city is divided by a cross or a “T” of the main streets’, for in each image ‘God’s order is expressed in geometric terms’ (illus. 36).12 The circular-shaped city was itself the innermost of a series of hierarchically arranged concentric rings that organized the whole of the Christian world spatially and geometrically from its centre, Jerusalem, outwards to the very edge of the celestial sphere. Hence the Jerusalem located at the centre of the Hereford world map (c. 1290) has the same topographical details as those found on Crusader maps of the city from the twelfth century (illus. 2).13

So although examples such as the Trinity Apocalypse manuscript show a square plan of the heavenly Jerusalem, as it is described in Scripture, an idealized form was also used depicting the city as a circle, as with the earlier, ninth-century Carolingian examples such as the Valenciennes heavenly Jerusalem (illus. 38). This particular image shows the city’s twelve gates, three situated on each opposing side of an encompassing walled circuit as scripture demanded, while the walled circuit itself is circular in form, depicted as twelve concentric rings, just like the order of the wider universe.14 The symbolic significance of this imagined form is discussed by Frugoni, who follows Gousset in pointing to ‘the choice of the circle as a symbol of perfection’, and the idea that ‘the circle is an image of the cosmos’, with the city’s gates positioned to form a cross, arranged to face the cardinal directions and point to the four corners of the world (a view first put forward some 50 years ago by Laveden).15 Therefore the imagined circular form of the heavenly Jerusalem mirrored the imagined geometrical shape of the wider world, their shared geometries connecting one and other. The circle symbolized Jerusalem’s cosmological importance.

| 2 Map of Jerusalem, twelfth century. |

Reconciling the heavenly city’s two geometrical forms – the imagined circle and the scriptural square – also had a cosmological basis. Like the heavenly Jerusalem, the cosmos was also thought to be both circular (according to Neoplatonic cosmological sources) and square-shaped (according to Holy Scripture) (see below). To square the circle, illustrations of the city combined the geometries of the circle and square, a technique used in contemporary depictions of the medieval world as well as images of the holy city. For example, depictions of the circular Jerusalem, such as the Valenciennes manuscript, show opposing gates that form a quartered city, its cross-shape anchored to the cardinal points and the four quarters of a quadrate world. Another way that the imagined form of the heavenly city was geometrically connected to the wider Christian world is evident in the Triers Apocalypse manuscript where, as Frugoni has pointed out, the illustration shows a circle of walls but this time with emphasis on four of the wall’s towers, which are coloured differently from the rest so as to form ‘an ideal square’, as scripture required (illus. 37).16 Combining circle and square in this way not only reconciled the two forms of the heavenly city, it also connected city with cosmos. By having shared forms – the circle and the square – the heavenly city and the wider cosmos were mirroring each other; their imagery squaring the imagined circular cosmological form of the celestial city with how it and the world at large are both described in scripture, the word of God. These images of a geometrical heavenly Jerusalem, and the forms given to the celestial city, were also superimposed onto earthly cities, including Jerusalem itself, so connecting the metaphorical, imagined ‘city’ of God with the earthly ‘cities of man’.

Depicting the holy city

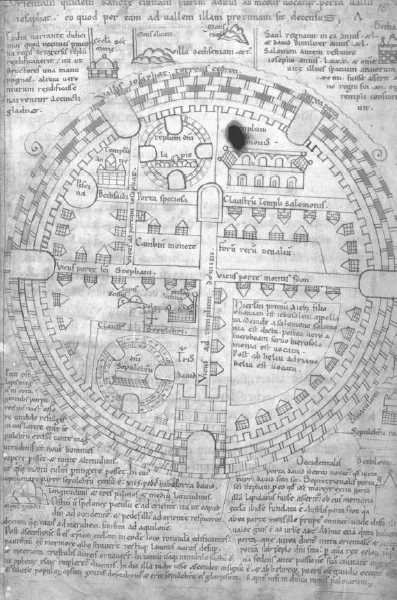

Like its heavenly archetype, the earthly Jerusalem was also often depicted as circular in form. In Crusader descriptions of the city of the twelfth century it has a circle of walls pierced by gates positioned at three of the four cardinal points, with streets arranged to form a cross-shape and various landmark buildings indicated, such as the Templum Domini (illus. 2, 3 and 41).17 This idea of the earthly Jerusalem as itself a reflection of the heavenly city gained currency in the context of the Crusader withdrawal from the city. Its ‘loss’ in the late twelfth century from Latin Christendom, and the desire to fight for and defend the city ‘against the Infidel’, is clear in a twelfth-century Crusader map of Jerusalem complete with fighting knights outside (‘beneath’) the circular-walled city with its cross of streets (illus. 41).18

| 3 Map of Jerusalem, thirteenth century. |

While not all medieval images of the earthly Jerusalem used the same circular form as the celestial city – the thirteenth-century map of Jerusalem drawn by Matthew Paris for his Chronica Majora shows the city as square-shaped, for example – its circular form generally did predominate, as it did in images of the heavenly Jerusalem.19 That the two Jerusalems shared a common form and layout is therefore clear. Their characteristics point to Jerusalem as an archetype, an idealized urban model visualized in abstract geometrical form.20 As Alexander notes, ‘in many representations of Jerusalem all that is required are walls’, depicted as a circle- or square-walled circuit, ‘surrounding buildings to signify [the] “city”.’21 These shared forms of the two Jerusalems circulated around the medieval Christian world, ending up far away from Jerusalem itself in cities such as London, Paris, Munich, Stuttgart and Florence.22 Their impact on the minds of those who saw them can now only be estimated, yet something of their influence can be gauged by how this imagery of a circular Jerusalem took form in representations of other, European, towns and cities in the Latin West.

Medieval maps of Europe’s towns and cities have yet to be brought together in a critical study.23 Stylized urban representations of all sorts – not just ‘maps’ but other images, too – tend towards showing the city as having a circular or square form, seemingly deliberately and self-consciously imitating the forms of Jerusalem with its cosmological symbolism. Some medieval towns and cities really were geometrical in shape.24 In those comparatively rare cases where urban forms are described or depicted by contemporaries, they were represented in such a way that over-emphasized beyond reality either the roundness or rectilinearity of their shape. One such example is a late-medieval representation of the city of Bristol (illus. 42). This appeared in a mayoral register begun by Robert Ricart, the town clerk, in the late fifteenth century, and with its circle of walls and four streets arranged in a cross-shape terminating at four gates, the image of Bristol has more than a superficial resemblance to those of Jerusalem.25 However...