![]()

Chapter 1

The History of Chocolate

Chocolate is almost unique as a food in that it is solid at normal room temperatures yet melts easily within the mouth. This is because the main fat in it, which is called cocoa butter, is essentially solid at temperatures below 25 °C when it holds all the solid sugar and cocoa particles together. This fat is, however, almost entirely liquid at body temperature, enabling the particles to flow past one another, so the chocolate becomes a smooth liquid when it is heated in the mouth. Chocolate also has a sweet taste that is attractive to most people.

Strangely chocolate began as a rather astringent, fatty and unpleasant tasting drink and the fact that it was developed at all is one of the mysteries of history.

1.1 Chocolate as a Drink

As early as 1900 BC cocoa was being used as a beverage by the Mokaya people in Mexico.1 Cocoa plantations were grown by the Maya in the lowlands of south Yucatan about 600 AD and cocoa trees were being grown by the Aztecs of Mexico and the Incas of Peru when Europeans discovered Central America. The beans were highly prized and used as money, where its actual value varied according to quality and type. There was even a special currency variety called quauhcacaoatl.2 Counterfeit beans filled with wax have been discovered.

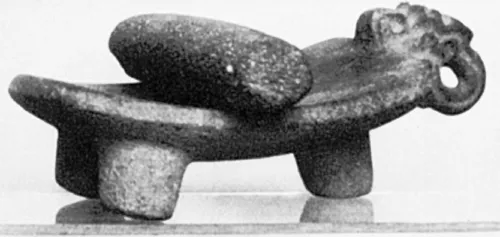

The main use of cocoa beans, however, was to produce a drink known as chocolatl. The beans were roasted in earthenware pots and crushed between stones, sometimes using decorated heated tables and mill stones, similar to that illustrated in Figure 1.1. They could then be kneaded into cakes, which were added to cold water to make a drink. Vanilla, spices or honey were often added and the drink whipped to make it frothy.3 The Aztec Emperor Montezuma was said to have drunk 50 jars of this beverage per day.

Figure 1.1 Ancient decorated mill stone with a hand grinder from the Yucatan.

(Reproduced from ref. 7 with permission from Springer Nature, Copyright 1965.)

Christopher Columbus brought back some cocoa beans to Europe as a curiosity, but it was only after the Spaniards conquered Mexico that Don Cortez introduced the drink to Spain in the 1520s. Here sugar was added to overcome some of the bitter, astringent flavours, but the drink remained virtually unknown in the rest of Europe for almost a hundred years, coming to Italy in 1606 and France in 1657. It was very expensive and, being a drink for the aristocracy, its spread was often through connections between powerful families. For example, the Spanish princess Anna of Austria introduced it to her husband King Louis XIII of France and the French court in about 1615. Here Cardinal Richelieu enjoyed it both as a drink and to aid his digestion. Its flavour was not liked by everyone and one Pope in fact declared that it could be drunk during a fast, because its taste was so bad.

The first chocolate drinking meeting place was established in London in 1657 and was mentioned in Pepys’ Diary of 1664 where he wrote that “jocolatte” was “very good”. In 1727 milk was being added to the drink. This invention is generally attributed to Nicholas Sanders4 or Sir Hans Sloane,5 founder of The British Museum. Their recipe was purchased and used by the Cadbury family. During the eighteenth century, White’s Chocolate House became the fashionable place for young Londoners, while politicians of the day went to the Cocoa Tree Chocolate House. These were much less rowdy than the taverns of the period. It remained, however, very much a drink for the wealthy.

One problem with the chocolate drink was that it was very fatty. Over half of the cocoa bean is made up of cocoa butter. This will melt in hot water making the cocoa particles hard to disperse, as well as looking unpleasant because of fat coming to the surface. The Dutch, however, found a way of improving the drink by removing part of this fat. In 1828 Van Houten developed the cocoa press. This was quite remarkable, as his entire factory was manually operated at the time. The cocoa bean cotyledons (known as cocoa nibs) were pressed to produce a hard “cake” with about half the fat removed. This was milled into a powder, which could be used to produce a much less fatty drink. In order to make this powder disperse better in the hot water or milk, the Dutch treated the cocoa beans during the roasting process with an alkali liquid. This has subsequently become known as the Dutching process. By changing the type of alkalizing agent, it also became possible to adjust the colour of the cocoa powder.

1.2 Eating Chocolate

Having used the presses to remove some of the cocoa butter, the cocoa powder producers were left trying to find a market for this fat. This was solved by confectioners finding that “eating” chocolate could be produced by adding it to a milled mixture of sugar and cocoa nibs. (The ingredients used to make dark chocolate are shown in Figure 1.2.) If only the sugar and cocoa nibs were milled and mixed together they would produce a hard crumbly material. Adding the extra fat enabled all the solid particles to be coated with fat and thus form the hard uniform bar that we know today, which will melt smoothly in the mouth.

Figure 1.2 Unmilled ingredients used to make dark chocolate.

(Reproduced with permission of Dr P Ashby, Copyright 2017.)

Almost 20 years after the invention of the press in 1847, the first British factory to produce a plain eating chocolate was established in Bristol in the UK by Joseph Fry.

Unlike Van Houten, Fry used the recently developed steam engines to power his factory. Interestingly, many of the early chocolate companies, including Cadbury, Rowntree and Hershey (in the USA), were founded by Quakers or people of similar religious beliefs. This may have been because their pacifist and teetotal beliefs prevented them from working in many industries. The chocolate industry was, however, regarded as being beneficial to people. Both Cadbury and Rowntree moved to the outside of their cities at the end of the 1890s, where they built “garden” villages for some of their workers. Fry remained mainly in the middle of Bristol and did not expand as quickly as the other two companies. It eventually became part of Cadbury.

With the development of eating chocolate, the demand for cocoa greatly increased. Initially much of the cocoa came from the Americas, with the first cocoa plantation in Bahia in Brazil being established in 1746. Even earlier, however, the Sp...