![]()

1

Speaking and listening

Introduction

This chapter covers:

- how and why children learn to talk;

- the connection between language and learning;

- organising for speaking and listening;

- drama;

- speaking and listening across the curriculum;

- standard English and received pronunciation.

Children learning language

Language acquisition

By the time that children are four or five almost all of them have achieved an amazing competence in at least one language. Studies of the vocabulary development of young children have shown that the average five-year-old knows at least 2,000 words and may know over 10,000 (Crystal, 1987). The number of words that a young child understands is thought to be far more than either of these figures. As part of the process of gathering this extensive vocabulary, most young children have mastered most of the phonemes or sound units of the speech used in their home or community. Research has shown that, by the time they go to school, children’s speech is mostly grammatically correct and children from English-speaking homes use all the basic sentence patterns of English in their speech (Strickland, 1962; Loban, 1976). Although some children may make grammatical errors, saying, for example, ‘she bringed it’ rather than ‘she brought it’, such mistakes are usually the result of the overgeneralisation of a grammatical rule rather than a random mistake, in this case an awareness of how past-tense verbs are often formed. As well as being competent speakers young children are also expert listeners. It is their ability to listen that allows them to join in with the speech of adults from the time that they are a few months old. Listening gives them clues about the sounds and sound combinations which are used to form acceptable words and provides children with an understanding of how sentences are formed.

By the age of three or four months children are actively developing as participants in spoken communication. Babies respond to the talk of others with smiles, movements and sounds. They discover their own voices and gurgle with pleasure as adults speak to them. This stage in language development, known as babbling, gives very young children the opportunity to experiment with and imitate the sound patterns of their home language. As children experiment with producing sounds they gain greater control over their throat and mouth muscles and begin to engage in turn-taking behaviour, characteristic of spoken dialogue. For example, they wait for a pause in the speech of others before producing their own sounds. By about five or six months babies may begin intentionally to use their voices to attract attention and to initiate social exchanges. During the next few months babies start to establish a range of sounds, some of which are wordlike. These might include sounds such as ‘baba’, ‘da-da’ and ‘mama’. Adults are often delighted with the emergence of sounds that resemble familiar words and attribute meaning to them. They respond to children by repeating and expanding those words that they recognise, saying such things as, ‘Da-da, yes, what a clever girl. Here’s daddy now. Daddy is opening the door.’ With encouragement such as this children gradually begin to attach meaning to particular groups of sounds and words, hearing, for example, that ‘da-da’ can become the word ‘daddy’. Adult responses encourage babies to experiment more and provide examples which children use to build a vocabulary that sounds increasingly like that of adult speakers.

From the age of about 15 months onwards, children begin, with increasing accuracy, to imitate the sounds that they hear others use. They show that they want to join in communicative acts with others, signalling their intentions through their actions, gestures and the tone and nature of their utterances. Their communications increasingly resemble the words and phrases used by the adults around them. At about two years children’s speech is characterised by abbreviated utterances that transmit meaning (Brown and Belugi, 1966). They produce correctly ordered groups of content words that can be understood by others. For example, a young child may say, ‘Mummy gone shops’. The typical adult response to an utterance of this sort is to acknowledge the meaning, praise the utterance and expand what was said by giving the child the ‘correct’ adult version by replying ‘Yes, that’s right. Mummy has gone to the shops, hasn’t she?’ This kind of response provides children with models of the extended grammatical structure of language which they incorporate into their own speech. From about the age of three years most children begin to construct longer, more complex sentences and are able to use a number of tenses and styles. Their development as speakers and listeners continues until, by the time they start school, the majority of children are accomplished communicators with a large vocabulary, a command of a range of sentence types and a clear sense of grammatical correctness.

How and why children learn to speak

Most children develop their capacity to speak and to listen without any direct instruction or teaching. How children do this reveals a great deal about them as learners generally as well as about how they learn language. Adults can learn from this process. Understanding the way children develop speaking and listening provides teachers with an understanding of the conditions that support learning and strategies which help children to learn.

Babies are learners from the moment of their birth. The first cry that they utter as they are born, as with their later cries and sounds, results in attention and responses from those around them. From the start adults respond to children’s facial expressions and the sounds that they make, with encouragement, praise and an expectation that the child’s communication has meaning. At the same time as babies are learning that producing sounds enables their needs to be met, the adults who surround them are demonstrating the nature and use of speaking and listening. Care-givers assume that even very young babies are potential conversation partners and as they interact with babies they speak to them in a way that assumes that the baby is listening, may understand and has the potential to respond. Children overhear a great deal of conversation between those around them and are exposed to a great deal of conversation addressed directly to them. Adults interpret, repeat, support, extend and provide models of speech for children as they communicate with them. They do not limit their language or the child’s learning but rather expose the child to the full range of language that is used in the child’s environment. As children are exposed to more and more language and are supported in their production they become increasingly proficient in their language use.

At first babies use language for functional reasons; to express their needs and to get others to do things for them. At an early stage they may also see the social purposes of language. Because the attention of others is usually pleasurable babies soon discover that the production of sounds and language is one way for them to initiate and sustain interactions. Babies seem to enjoy producing sounds and at times produce long repetitions of similar sounds as they babble and gurgle and later experiment with real and nonsense words. Finally children seem to develop language because they are cognitive beings and active explorers of their worlds. Language is one method of finding out about the world that they live in. It enables them to widen their understanding by questioning, commenting, suggesting reasons, drawing upon previous experience and receiving information from others.

Language and learning

Being able to listen and to speak are essential if children are to succeed both inside and outside school. Speaking and listening occupy more time than reading and writing in the lives of most people. In school a developing facility with oral language is crucial for learning. In the early years a great deal of teaching and assessment is carried out through talk as the teacher explains, describes and questions children.

Learning to read and to write are founded upon children’s oral language competence. As they learn to speak they discover that language contains meaning, follows a particular structure and consists of sentences, words and parts of words. They can apply this knowledge about language as they learn to read and write. As children progress through the education system knowledge and information are increasingly transmitted and recorded through reading and writing and their learning depends on a growing competence in a language mode that grows out of their ability to speak and listen.

From the start children’s language development is associated with their exploration and growing understanding of the world they inhabit. Through listening, hypothesising, questioning and interpreting the responses they receive from others they learn a great deal. Language supports children’s cognitive development by providing them with a tool to make discoveries and make sense of new experiences and offering them a means of making connections between the new and what is already known. All learning depends on the ability to question, reason, formulate ideas, pose hypotheses and exchange ideas with others. These are not just oral language skills, they are also thinking skills. We explore what we think and know through language. As we share events and describe our emotions to others and try to find the correct way of expressing these we often begin to discover what we really remember, feel or understand. Talk can help us to clarify and focus our thinking and deepen our understanding. As we struggle with expressing our ideas to others we often understand them more clearly ourselves. So perhaps the most important reason for developing children’s oral language is the link between language development, learning and thinking. This kind of talk is not one where there are swift, short ‘right answers’. It is often tentative. Words are changed and ideas expressed in a number of different ways. In order for the link between thinking and talking to be realised, children need time to think about what they know, time to think about how to express their thoughts and time to articulate and reformulate their ideas.

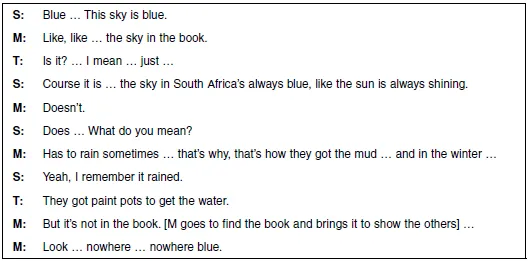

The extract in Figure 1.1 shows the potential language has to be a powerful tool for learning across and beyond the early years curriculum. Three Year 1 children, Suki, Martin and Thomas, were working together in the art area. They had been asked to print a large area of sky as part of a background for a display relating to the story Charlie’s House (Schermbrucker, 1992). The teacher had asked the children to work together to complete the activity. They had to decide on the colour they would use for the sky and then decide what equipment they would use for the printing.

This extract shows children using talk to focus carefully on the activity and to do it well. They were using talk for a number of purposes and in a number of ways. Through their talk they were reflecting on a previous learning experience which occurred when they listened to the story, and integrating this with their own knowledge and understanding of hot countries. Although they had seen the pictures in the book, they had not realised the significance of the grey skies in relation to the climate. Martin’s contribution is an excellent example of taking time to think and express his growing understanding through talk. At first he seems prepared to go along with Suki’s suggestion but Thomas’s question prompts his thinking. He then disagrees quite bluntly before being able to justify his new position. Thomas also gives reasons for his opinion after taking some time to think. As the children talk they listen carefully to one another and give each other time, and Suki seems happy to adjust her thinking in the light of what has been said and the evidence contained in the book. Exchanging ideas has given them the opportunity to re-evaluate what they assumed and to extend and amend their previous knowledge. Had the children been working at this task singly or with an adult who was directing them, it is unlikely that this learning and reflection would have taken place. In this extract the conversation emerging from a collaborative activity has been a valuable way of exchanging opinions, sharing knowledge, justifying ideas, reflecting on previous experiences and accepting new learning.

Figure 1.1 Children learning through talk

Concerns and solutions about teaching speaking and listening

For some time speaking and listening was a neglected element in the English curriculum. The publication of the National Literacy Strategy (DfEE, 1998) placed the emphasis for English teaching firmly on reading and writing and classroom practice reflected this. More recently the importance of teaching speaking and listening has been recognised. In 2003 new guidelines were developed by the DfES to support teachers and the Primary Framework for Literacy (DfES, 2006a) contains yearly objectives for oral language as well as for reading and writing. The review which preceded the framework (Rose, 2006) also recommended that the teaching of reading should be accompanied by teaching which develops children’s abilities in speaking and listening. These publications are doing a great deal to ensure that speaking and listening have a significant place in the English curriculum.

Classroom management

Routines and rules about quiet or silence while the teacher marks the register, when children move from the classroom for PE, lunch, playtime and assemblies and silent periods for reading, PE and stories reduce the time available for talk in the school day. Too many rules about times when children’s talk is not allowed can also transmit negative messages about the importance of talking and listening.

Sometimes teachers think that the sound of children talking signals that children are not working and tell children to ‘Be quiet’ and ‘Stop talking’ so that they can get on with their work. They may fear that talk will develop into noisy and undisciplined behaviour. Teachers who do not understand the place of talk in learning and who feel insecure about noise in the classroom will influence their pupils’ perceptions of talk. When children are taught by teachers who silence them or who suggest that talking is not work they learn that speaking and listening have little status at school. They will not see speaking and listening as a means of learning, and when they are given opportunities to speak often use talk to chat or gossip.

Teachers can find the prospect of organising collaborative activities for the whole class daunting. They may restrict opportunities for developing speaking and listening to whole-class discussion times or believe that allowing quiet talking when children work is sufficient. Whole-class discussions are rarely productive and their use needs to be limited. The majority of children are usually silent while one child or the adult speaks, very few children get the opportunity to contribute and interaction among the children is rare. Permitting quiet talking during an activity is not the same as children talking about an activity and using talk to exchange ideas, to question, to solve problems and to explain. Collaborative activities that demand pupil discussion need to be consciously organised by the teacher – productive talk does not just happen.

Teacher talk

The pressure to cover the s...