Chapter 1

Child of a Drowned Parent

Physical Geography

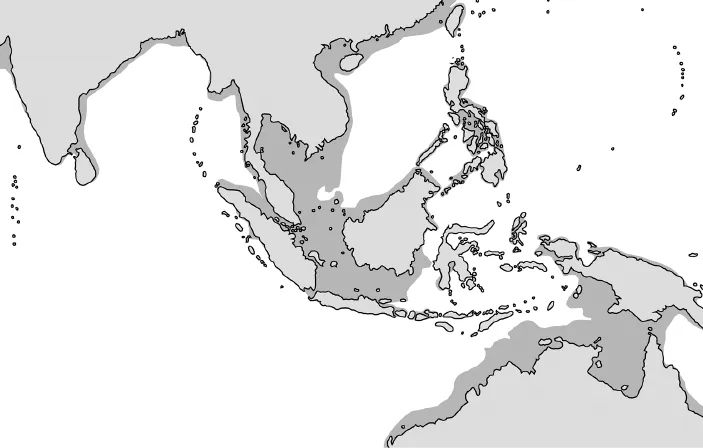

Nusantaria is a relatively new creation. Figure 1 is a map of South East Asia approximately 17,000 years ago. There is no Java Sea nor Melaka strait; the South China Sea is much smaller than today; Sumatra, Java, Taiwan and Hainan are not islands.1 Even by the standards of humans, 17,000 years is not so very long ago considering that modern man reached New Guinea and Australia 50,000 years ago. A huge rise in sea level between 20,000 bp and 7000 bp flooded a large part of the Sunda Shelf, which had been, prior to that rise, part of the Asian mainland. A more modest rise continued till about 4000 bp, then a small decline gave back some land. Since then the general sea level has been, until very recently, relatively steady for the past 1,000 years.

The years of rising seas also flooded some of the Sahul Shelf, of which New Guinea and Australia are the main components. Of present day South East Asia, only the Philippines (except Palawan), Sulawesi and the eastern Indonesian islands were separate from either shelf. One exception was Sumba, a mainly sandstone island which had once been part of either Sundaland or Sahuland but drifted off.2 The other islands of that intermediate region, now named ‘Wallacea’ after the nineteenth-century naturalist Alfred Russell Wallace, are volcanic.3

Map 1. Land at 15,000 BP.

Map 2. Land at 11,000 BP.

Going back further in time, much of the South East Asian landmass was originally formed when, millions of years ago, parts of the ancient vast southern continent of Gondwanaland broke off and moved north. Some joined the northern continent, which has been named Laurasia and now forms the Indian subcontinent and parts of mainland South East Asia.

These landmass movements continue, affecting daily life today, as well as determining development measured in millions of years. Sumatra, Java and most of the islands of eastern Indonesia sit just north of a massive fault line as the Australian plate pushes north. This makes the archipelago the most earthquake- and volcano-prone place in the world. To the north-east is another fault line where the Indian plate meets the Philippine plate. The Philippine islands, except Palawan, are on their own plate, possibly having once been part of a larger one that has been much altered since by volcanic eruptions.

The last ice age peak was about 22,000 years ago, but modern man and his predecessors had been living with huge climate shifts for much longer. The changes in temperature and the coming and going of the sea played a critical part in the much earlier history of humans in this region, including Homo Erectus and Neanderthal man. The discovery of so-called Java Man in 1891 was the first of several finds of Homo Erectus on Java between 1 million and 600,000 years ago. Sangiran near Solo in central Java has yielded one of the largest collection of Homo Erectus remains in the world and provided important evidence of man’s evolutionary progress.

There was not just one great ice age. Over the past 250,000 years there have been several periods of a warmer planet and higher seas, but the average sea level over the period was about 40 metres below that of today. At the peak of the last ice age, around 21,000 bp, the Eurasian landmass almost reached Australia. At that low point – a sea level of about 120 metres below today – some three million square kilometres of what is now sea were dry land with plains, hills and river systems. The Japanese islands were joined up; Kyushu was linked to what is now the Korean peninsula and to Taiwan via the Ryukyu islands.4 After that, the rate of sea level rise varied enormously: about 80 metres of the rise occurred in just 7,000 years. Around 14,000 bp it rose five metres in 100 years – compare this with a recent rate of about 20 centimetres per 100 years. Around 11,000 bp the level was 50 metres below the current level. At that time mainland Asia was still joined to Sumatra, Java, Borneo and Hainan and Taiwan. The rise between 11,000 and 7000 bp, after which sea levels became relatively stable, defined today’s maritime region centred on the drowned Sunda Shelf.5

It is becoming clearer from the study of seabeds that the defining event in creating Nusantaria, the flood, was not a gradual process of a centimetre a decade. There is evidence of sudden increases driven by the collapse of ice fields and changes in pressures on the earth’s crust creating earthquakes and tsunamis. Such sudden changes probably explain the Biblical flood ‘myth’ found in many cultures.6

Even at the lowest sea levels of the last ice age, there was deep water between Bali on the edge of the Sunda Shelf and the Sahul Shelf. But the distances were small enough for humans – though not for many animal species – to cross. It was during the last great glaciations that modern humans reached Australia, most likely arriving via Wallacea. New Guinea was reached about the same time and became, around ten thousand years ago, probably the first place on earth – long before Egypt or Mesopotamia – where settled agriculture was practised.

Human Geography, or BioGeography

The sea rise also created a genetic and cultural rift. By modern times there was a clear racial divide between the Malay-Polynesians, speaking Austronesian languages, and Papuan-Melanesian physical types and cultures. Despite their remarkable east to west dispersal, the former left little trace in lands that were relics of the Sahul Shelf other than in the Bismarck Archipelago. However, some Melanesians remained further west. Findings from Niah cave in Sarawak dated to about 40,000 years ago and at Tabon on Palawan dated to 25,000 years ago have genetic characteristics similar to ancient Australians and Melanesians.7 So it is likely that the first Homo Sapiens in the region were of the same stock as the Australo-Melanesians who settled the forests and highland valleys of New Guinea and the bush country and great deserts of Australia. The Tabon caves were inhabited from around 30,000 bp, but while they now overlook the sea they were once on a hillside far from the shore. Thus far, no similar finds have been made on other islands, which may suggest that Tabon man walked there and that early man in that region had yet to gain sufficient skills to cross from Palawan to Mindanao or the Visayas.

The deep water gaps between Wallacea and the Sahul and Sunda landmasses had a huge impact on fauna and flora. Until later introduced by humans, large placental mammals never crossed that divide from Sundaland to Wallacea nor did large marsupials move in the other direction. Wallacea had its own separate but rather limited indigenous fauna and flora due to its weak links to the great landmasses and the distance in time since it had drifted from Gondwanaland.

The ending of the last ice age must have been a catastrophe for many of the people of Sundaland, the relatively flat land between what is now the Asian mainland and the coasts of Sumatra, Java and Borneo. While global warming enabled areas such as northern Europe to become habitable, in Asia it destroyed large numbers of human settlements in a region which previously should have been very conducive to habitation. By the same token, the creation of many islands and a huge expansion of coastlines produced the environment for the world of the Nusantarians, living on and by the sea, developing sailing craft and navigational prowess and building the coastal exchange networks which eventually evolved into ocean-spanning movements. They were behind the expansion of human settlement and of trade around half the globe. The same people, originating from Nusantaria, settled almost every island between Rapa Nui (Easter Island) and Madagascar, between Taiwan and New Zealand.

Today, the majority of people from Nusantaria are defined as ‘Austronesians’ – a Greek-derived word meaning ‘southern islands’ but now applied to a language group. Austronesian is in the first instance a linguistic marker though also with shared genetic and cultural...