eBook - ePub

The Biology of Parasites

Richard Lucius, Brigitte Loos-Frank, Richard P. Lane, Robert Poulin, Craig Roberts, Richard K. Grencis, Ron Shankland, Renate FitzRoy

This is a test

Buch teilen

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

The Biology of Parasites

Richard Lucius, Brigitte Loos-Frank, Richard P. Lane, Robert Poulin, Craig Roberts, Richard K. Grencis, Ron Shankland, Renate FitzRoy

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

This heavily illustrated text teaches parasitology from a biological perspective. It combines classical descriptive biology of parasites with modern cell and molecular biology approaches, and also addresses parasite evolution and ecology.

Parasites found in mammals, non-mammalian vertebrates, and invertebrates are systematically treated, incorporating the latest knowledge about their cell and molecular biology. In doing so, it greatly extends classical parasitology textbooks and prepares the reader for a career in basic and applied parasitology.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist The Biology of Parasites als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu The Biology of Parasites von Richard Lucius, Brigitte Loos-Frank, Richard P. Lane, Robert Poulin, Craig Roberts, Richard K. Grencis, Ron Shankland, Renate FitzRoy im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Biological Sciences & Neuroscience. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Chapter 1

General Aspects of Parasite Biology

Richard Lucius and Robert Poulin

- 1.1 Introduction to Parasitology and Its Terminology

- 1.1.1 Parasites

- 1.1.2 Types of Interactions Between Different Species

- 1.1.2.1 Mutualistic Relationships

- 1.1.2.2 Antagonistic Relationships

- 1.1.3 Different Forms of Parasitism

- 1.1.4 Parasites and Hosts

- 1.1.5 Modes of Transmission

- Further Reading

- 1.2 What Is Unique About Parasites?

- 1.2.1 A Very Peculiar Habitat: The Host

- 1.2.2 Specific Morphological and Physiological Adaptations

- 1.2.3 Flexible Strategies of Reproduction

- Further Reading

- 1.3 The Impact of Parasites on Host Individuals and Host Populations

- Further Reading

- 1.4 Parasite–Host Coevolution

- 1.4.1 Main Features of Coevolution

- 1.4.2 Role of Alleles in Coevolution

- 1.4.3 Rareness Is an Advantage

- 1.4.4 Malaria as an Example of Coevolution

- Further Reading

- 1.5 Influence of Parasites on Mate Choice

- Further Reading

- 1.6 Immunobiology of Parasites

- 1.6.1 Defense Mechanisms of Hosts

- 1.6.1.1 Innate Immune Responses (Innate Immunity)

- 1.6.1.2 Acquired Immune Responses (Adaptive Immunity)

- 1.6.1.3 Scenarios of Defense Reactions Against Parasites

- 1.6.1.4 Immunopathology

- 1.6.2 Immune Evasion

- 1.6.3 Parasites as Opportunistic Pathogens

- 1.6.4 Hygiene Hypothesis: Do Parasites Have a Good Side?

- 1.6.1 Defense Mechanisms of Hosts

- Further Reading

- 1.7 How Parasites Alter Their Hosts

- 1.7.1 Alterations of Host Cells

- 1.7.2 Intrusion into the Hormonal System of the Host

- 1.7.3 Changing the Behavior of Hosts

- 1.7.3.1 Increase in the Transmission of Parasites by Bloodsucking Vectors

- 1.7.3.2 Increase in Transmission Through the Food Chain

- 1.7.3.3 Introduction into the Food Chain

- 1.7.3.4 Changes in Habitat Preference

- Further Reading

1.1 Introduction to Parasitology and Its Terminology

1.1.1 Parasites

Parasites are organisms which live in or on another organism, drawing sustenance from the host and causing it harm. These include animals, plants, fungi, bacteria, and viruses, which live as host-dependent guests. Parasitism is one of the most successful and widespread ways of life. Some authors estimate that more than 50% of all eukaryotic organisms are parasitic, or have at least one parasitic phase during their life cycle. There is no complete biodiversity inventory to verify this assumption; it does stand to reason, however, given the fact that parasites live in or on almost every multicellular animal, and many host species are infected with several parasite species specifically adapted to them. Some of the most important human parasites are listed in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Occurrence and distribution of the more common human parasites

| Parasite | Infected people (in millions) | Distribution |

| Giardia lamblia | >200 | Worldwide |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | 173 | Worldwide |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 500* | Worldwide in warm climates |

| Trypanosoma brucei | 0.01 | Sub-Saharan Africa (“Tsetse Belt”) |

| Trypanosoma cruzi | 7 | Central and South America |

| Leishmania spp. | 2 | Near + Middle East, Asia, Africa, Central and South America |

| Toxoplasma gondii | 1500 | Worldwide |

| Plasmodium spp. | >200 | Africa, Asia, Central and South America |

| Paragonimus sp. | 20 | Africa, Asia, South America |

| Schistosoma sp. | >200 | Asia, Africa, South America |

| Hymenolepis nana | 75 | worldwide |

| Taenia saginata | 77 | Worldwide |

| Trichuris trichiura | 902 | Worldwide in warm climates |

| Strongyloides stercoralis | 70 | Worldwide |

| Enterobius vermicularis | 200 | Worldwide |

| Ascaris lumbricoides | 1273 | Worldwide |

| Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus | 900 | Worldwide in warm climates |

| Onchocerca volvulus | 17 | Sub-Saharan Africa, Central and South America |

| Wuchereria bancrofti | 107 | Worldwide in the tropics |

Source: Compiled from various authors.

*many of those asymptomtic or infected with the morphologically identical Entamoeba dispar.

The term parasite originated in Ancient Greece. It is derived from the Greek word “parasitos” (Greek pará = on, at, beside; sítos = food). The name parasite was first used to describe the officials who participated in sacrificial meals on behalf of the general public and wined and dined at public expense. It was later applied to minions who ingratiated themselves with the rich, paying them compliments and practicing buffoonery to gain entry to banquets where they would snatch some food.

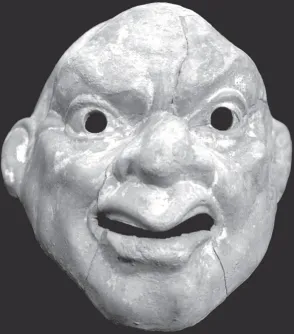

The result was a character figure, a type of Harlequin, who had a fixed role to play in the Greek comedy of classical antiquity (Figure 1.1). Later, “parasitus” also became an integral part of social life in Roman antiquity. It also reappeared in European theater in pieces such as Friedrich Schiller's “Der Parasit.” In the seventeenth century, botanists were already describing parasitic plants such as mistletoe as parasites; in his 1735 standard work “Systema naturae,” Linnaeus first used the term “specie parasitica” for tapeworms in its modern biological sense.

Figure 1.1 Parasitos mask, a miniature of a theater mask of Greek comedy; terracotta, around 100 B.C. (From Myrine (Asia Minor); antiquities collection of the Berlin State Museums. Image: Courtesy of Thomas Schmid-Dankward.)

The delimitation of the term “parasite” to organisms which profit from a heterospecific host is very important for the definition itself. Interactions between individuals of the same species are thus excluded, even if the benefits of such interactions are very often unequally distributed in the colonies of social insects and naked mole rats, for instance, or in human societies. As a result, the interaction between parents and their offspring does not fall under this category, although the direct or indirect manner in which the offspring feed from their parent organism can at times be reminiscent of parasitism.

The principle of one side (the parasite) taking advantage of the other (the host) applies to viruses, all pathogenic microorganisms, and multicellular parasites alike. This is why we often find that no clear distinction is made between prokaryotic and eukaryotic parasites. With regard to parasites, we usually do not differentiate between viruses, bacteria, and fungi on the one hand and animal parasites on the other; we tend to see only the common parasitic lifestyle. Even molecules to which a function in the organism cannot be assigned are sometimes described as parasitic, such as prions, for example, the causative agent of spongiform encephalopathy, or apparently functionless “selfish” DNA plasmids that are present in the genome of many plants. Many biologists are of the opinion that only parasitic protozoa, parasitic worms (helminths), and parasitic arthropods are parasites in the strict sense of the term. Parasitology, as a field, is concerned only with those groups, while viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasitic plants are dealt with by other disciplines. This restriction clearly hampers cooperation with other disciplines, something that seems antiquated in today's modern biology, where all of life's processes are traced back to DNA; it is gratifying that the boundaries have relaxed in recent years. However, eukaryotic parasites are distinguished from viruses and bacteria by their comparatively higher complexity, which implies slower reproduction and less genetic flexibility. These traits typically drive eukaryotic parasites to establish long-standing connections with their hosts, using strategies different from the “hit-and-run” strategies used by many viruses and bacteria....