eBook - ePub

Dictionary of Advertising and Marketing Concepts

Arthur Asa Berger

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 143 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Dictionary of Advertising and Marketing Concepts

Arthur Asa Berger

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

From AdBusters to viral marketing, this brief dictionary of ideas and concepts contains over 100 extended, illuminating entries to bring the novice up to speed on the advertising/marketing world and the ideas that underlie it. For the neophyte professional, it describes the various players and strategies of the industry. For the student, it summarizes the key ideas of the most important cultural theorists introduced in advertising and marketing courses. For everyone, it helps explain the cultural, economic, and psychological role that advertising concepts play in society. A handy introduction for students and a quick reference for young professionals.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Dictionary of Advertising and Marketing Concepts est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Dictionary of Advertising and Marketing Concepts par Arthur Asa Berger en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Lingue e linguistica et Studi sulla comunicazione. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

S

Semiotics

Semiotics is defined as the science of signs, which means it focuses upon the role of signs in society and, in particular, how people find meaning in various aspects of life. If advertisers are to communicate with their target audiences effectively, they must know how these target audiences think and the way they interpret signs and symbols. One problem is that we know that people don’t always interpret advertisements the way the people who create the ads expect them to. A number of years ago I met the president of an advertising agency in Britain who told me that people in his agency were very interested in semiotics, just as many semioticians are very interested in advertising.

Ferdinand de Saussure and C. S. Peirce are the founding fathers of the science of semiotics, which deals with signs (the term “sēmeîon” means sign) and how people find meaning in them. A sign is anything that can be used to stand for something else. Thus, if we look at a print advertisement with a male and female model and textual material in it, everything in that advertisement can be considered a sign: the bodies of the man and the woman, the clothes they are wearing, their facial expressions, the color of their hair, the style of their hair, their body language, the content of the textual material, the typography used in the textual material, the spatiality of the advertisement, ad infinitum.

In Saussure’s book, Course in General Linguistics, he called his science semiology—literally, words about signs. In one of the foundational descriptions of the science of signs, he writes (1915/1966, New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 16):

Language is a system of signs that express ideas, and is therefore comparable to a system of writing, the alphabet of deaf-mutes, symbolic rites, polite formulas, military signals, etc. But it is the most important of all these systems.

A science that studies the life of signs within society is conceivable; it would be a part of social psychology and consequently of general psychology; I shall call it semiology (from Greek sēmeîon “sign”). Semiology would show what constitutes signs, what laws govern them. Since the science does not yet exist, no one can say what it would be; but it has a right to existence, a place staked out in advance.

This statement opens the study of all kinds of communication to us, for not only can we study symbolic rites and military signals, we can also study soap operas, situation comedies, and advertisements and commercials—and almost anything else—as “sign systems.”

He also explained what signs were: “The linguistic sign unites not a thing and a name, but a concept and a sound-image.…I call the combination of a concept and a sound-image a sign, but in current usage the term generally designates only a sound-image” (pp. 66–67). He divided signs into two components, a signifier (or “sound-image”) and a signified (or “concept”), and pointed out that the relationship between signifier and signified is arbitrary; these points were of crucial importance for the development of semiotics. He offered another idea of consequence—namely that concepts have no meaning in themselves. The meaning of concepts depends on the way they are different from their opposites.

As he explained (p. 118):

Concepts are purely differential and defined not by their positive content but negatively by their relations with the other terms of the system. Their most precise characteristic is in being what the others are not….Signs function, then, not through their intrinsic value but through their relative position.

Later, he added, “Everything that has been said to this point boils down to this: in languages there are only differences” (p. 120).

The most important difference, it turns out, is the bipolar opposition: hot and cold, rich and poor, beautiful and ugly, hero and villain. As Saussure wrote, “The entire mechanism of language… is based on oppositions” (p. 121). It is the very nature of language that makes us see things in terms of oppositions, and thus, concepts, for Saussure, mean something by not being their opposite. When we see an advertisement or a commercial, or any text, our minds function, automatically and involuntarily, to sort out the various oppositions: hero or villain, beautiful or ugly, something to buy or something to ignore.

The second founding father of semiotics, and the thinker who gave the science its name, semiotics, was Charles Peirce, who made an important distinction between three different kinds of signs: icons, indexes, and symbols. Icons signify by resemblance; indexes signify by cause and effect; and symbols signify on the basis of convention. As Peirce wrote:

Every sign is determined by its objects, either first by partaking in the characters of the object, when I call a sign an Icon; secondly, by being really and in its individual existence connected with the individual object, when I call the sign an Index; thirdly, by more or less approximate certainty that it will be interpreted as denoting the object, in consequence of a habit (which term I use as including a natural disposition), when I call the sign a Symbol. (Quoted in J. J. Zeman, “Pierce’s Theory of Signs,” in T. A. Sebeok, Ed., A Perfusion of Signs, 1977, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, p. 36)

The following chart offers examples of each kind of sign in Peirce’s theory:

Icons | Indexes | Symbols | |

Signify by: | Resemblance | Cause and effect | Convention |

Example: | Photograph | Fire and smoke | Cross, Flags |

Process: | Can see | Can figure out | Must learn |

We can see that there are differences between Saussure’s science of signs and Peirce’s, although both deal with signs and both theories have been very influential. Peirce also said a sign “is something which stands to somebody for something in some respect or capacity,” which means that meaning is always created by individuals (quoted in Zeman, p. 27). He also argued that the universe is “perfused with signs, if it is not composed exclusively of signs” (epigraph in Sebeok, p. vi). This suggests that since everything in the universe is a sign, semiotics is the “master” science!

Semiotics has been of considerable use to scholars dealing with advertising, since it helps us figure out how people find meaning in advertisements and commercials, and it is useful to people in the advertising industry who are interested in the same topic. There are a number of semiotic analyses of advertising, such as Marshall McLuhan’s The Mechanical Bride (though he doesn’t mention semiotics or use semiotic concepts, his analysis is semiotic in nature) and Judith Williamson’s Decoding Advertisements: Ideology and Meaning in Advertising. When you see the term “meaning” being used in a book’s title, there usually is a connection with semiotics.

Semiotics argues that we are always sending messages to others about ourselves, and others are sending messages about themselves to us. Semiotics has the goal of understanding the full significance of these messages and messages we get from advertisements and commercials, and how all these messages are interpreted or “decoded” by other people. One problem with signs is that they can be used to lie, which means that blonde you see may be a brunette and that man you see may be a woman and that woman you see may be a man. It is because we know that signs lie that we must become suspicious of all signs and of the advertisements and commercials that employ them so artfully.

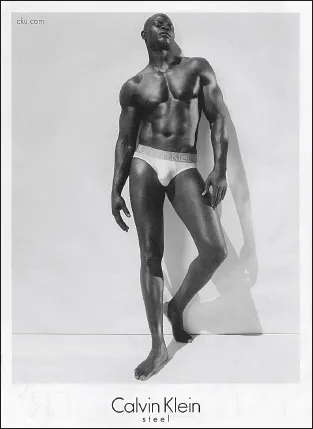

This Calvin Klein advertisement for underwear exploits the male body the way many advertisements exploit the female body: to sell products—in this case, underwear. It is only in recent years that the male body has been presented in advertisements as an object of sexual desire or lust.

Sexploitation

Until recently, sexploitation referred to advertisements that exploit the female body and female sexual allure to sell products and services. In recent years, the male body has been used for the same purposes. This is a relatively new phenomenon—exposing the male body to the desire and lust of others, male and female, I would presume—and the Calvin Klein advertisements provide an excellent example of this. Ther...