![]()

1

Introduction to Food Supply Chain Management

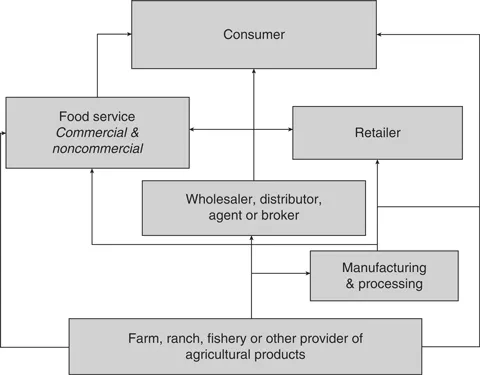

Today’s global food supply chain feeds over 310 million Americans and almost 7 billion more people around the world. Farms and ranches produce raw food products—grains, fruits, vegetables, meats and dairy—which then move by truck, rail or sea through a complicated distribution network that links processors, manufacturers, retailers, food service establishments and consumers, as illustrated in Figure 1.1. While food may be a relatively unremarkable aspect of most Americans’ lives, the food production process is actually deeply complex, influencing and influenced by natural, economic, cultural and political factors that are both national and international in scope. Comprehending these factors is critical to developing an informed opinion about the way we eat today, and the way we will produce food in the future as domestic and global populations increase.

What Do We Eat?

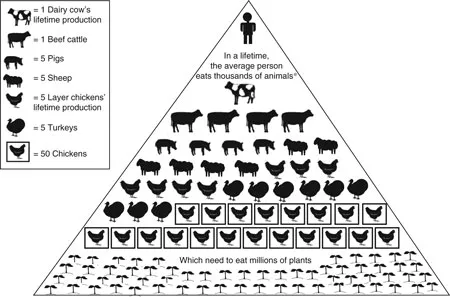

Today, most Americans enjoy a relatively high standard of living compared to people in developing countries. The average American consumes just under 2,000 pounds of food per year, including 630 pounds of dairy products, 413 pounds of vegetables, 273 pounds of fruit, 230 pounds of meat and non-dairy animal products, 192 pounds of grain-based products, 142 pounds of sweeteners and 85 pounds of fat. Perhaps not surprisingly, these numbers include a substantial amount of French fries, pizza and ice cream—29, 23 and 24 pounds, respectively. The estimated average lifetime consumption of food products for a person living in the developed world is illustrated in Figure 1.2.

In contrast, people in developing countries eat less than those in developed countries; i.e., they have fewer average per capita calories available to them each day—around 2,700, as opposed to the developing world’s 3,200 calories. Their eating patterns are also different, as they consume far more carbohydrates and starches and far fewer animal proteins and fats, which are expensive and resource-intensive to produce. While the overall supply of food in the world is, so far, adequate to meet caloric needs, vast discrepancies in food access exist—created primarily by poverty—resulting in substantial undernourishment and malnourishment in some populations. An estimated 925 million people in the world today are undernourished, meaning their caloric intake falls below minimum dietary requirements on a consistent basis. About 36 million people die each year due to malnourishment, or a lack of adequate nutrition.

Figure 1.1 The food supply chain

Figure 1.2 Food consumption in the developed world

*Not applicable to non-meat eaters or those that choose not to eat specific meats for religious reasons (Source: Compassion in World Farming)

The US population is expected to reach 440 million people by 2050. Global population is projected to reach over 9 billion in the next 40 years. Thus, food needs are going to increase as population expands. At the same time, the resources available to grow and produce food are going to decline, due to the inherent, non-farming related needs of human beings—land to live on, water to drink, fuel to drive, etc. It is estimated that for every person added to the US population, approximately one acre of land is lost due to urbanization and highway construction alone. At this rate, only 0.6 acres of farmland will be available to grow food for each American by 2050, as opposed to the 1.8 acres per capita that is available today. Other resource and cost implications associated with population growth are listed in Table 1.1.

The estimated carrying capacity of land—i.e., the estimated amount of land required to maintain current American dietary standards with current production practices—is 1.2 acres. Therefore, Americans will either need to significantly decrease or alter our food intake, change our food production practices, or pay more for food in the coming decades. Even with changes to consumption and production practices, food prices are projected to increase three- to five-fold by 2050. This will dramatically influence our existing quality of life and social balance, as Americans are used to spending a very small amount of our income on food—approximately 15%. In contrast, people in other developed countries spend 30% to 50% of their income on food, and those in developing countries spend, on average, 50% to 60% of their income on food.

If existing consumption and land use trends continue, researchers have also forecast that the United States will likely cease to be a food exporter by 2025, as all food grown in the United States will be needed for domestic consumption. Other countries that were once self-sufficient or were food exporters are already facing this problem. China, for example, used to produce enough corn and cereal products to meet its own demands. Today, however, it must import many commodities to meet demand. As America is one of the biggest agricultural producers in the world and a major food exporter, a halt to US food exports could dramatically reduce world food supplies—particularly staple crops, like grains—and increase global food costs, furthering nutritional inequality and instability in the world. It could also negatively influence our economic security, as our trade deficit will increase if not offset in some other way.

Table 1.1 Resource and Cost Implications for US Food Production

| | |

| Current Population | 2050 Population |

| | |

| 309 million | 520 million* |

Resource Availability Per Capita | | |

Arable Land | 1.8 acres | 0.6 acres |

Pasture Land | 2.3 acres | 1.1 acres |

Forest Land | 2.2 acres | 1.0 acres |

Fresh Water | 1,300 gallons | 700 gallons |

Energy | 2,500 gal. oil equivalents | 1,600 gal. oil equivalents |

Food Exports | $155 | $0 |

Other Impacts | | |

Diet Proportions | 69% plant, 31% animal | 85% plant, 15% animal |

Food Costs | N/A | 3- to 5-fold increase |

*Note that the 2050 population projection was recently adjusted by the US Census Bureau, to 440 million. Source: D. Pimentel and M. Giampietro.

Food is big business in America. Feeding our own population generates an estimated $1 trillion in consumer sales each year. The food industry accounts for 17% of the worker population, and 12% of gross national product. Approximately 20% of the agricultural products grown in America are exported, comprising 9% of US exports valued at about $115 billion each year. In addition to international trade, we supply vast quantities of food to humanitarian service organizations, who directly distribute surplus commodities to disasterand poverty-stricken people throughout the world. Clearly, finding a way to meet our own and others’ food needs in the future is a critical domestic and global priority. The question for many is how this is best achieved.

Schools of Thought

Today, several opposing schools of thought exist, each striving to answer the question of how to best feed the world. Some argue that the problem of global scarcity is best addressed by continuing to industrialize. In this model, the focus is on increasing yields, or increasing food supplies through more intensive farming and the application of biotechnologies. Others feel that the entire food production system needs to be reconceptualized—from the agricultural process to food distribution and waste management—in order to address the numerous environmental and economic issues that are currently resulting from the industrialized food production model. Both approaches have merits, and both have possible drawbacks that, if they come to fruition, could have negative consequences for the food supply, and thus, humanity.

The industrial perspective’s primary merit is that it is already in play and has momentum; the vast majority of agricultural lands are already being farmed using an industrialized model, and this model has proven to be effective, so far, in producing sufficient calories to meet global demand. Its drawbacks, however, are numerous, and include significant ecological destruction, such as topsoil loss and water contamination; an increasing reliance on nonrenewable resources, like petroleum-based fertilizers, to enhance agricultural yields; and, in all likelihood, increasing reliance on genetically modified organisms (GMOs) to help manage impending resource constraints—e.g., drought-resistant seeds. This latter issue is further problematic as GMO crops are already having a deleterious impact on plant diversity and the ecosystem, due to cross-pollination with wild plants. GMOs also increase the dependency of individual farmers, and thus the entire food supply, on the few companies that create GMO seeds, since GMO seeds are patented and must be repurchased each year, as opposed to being saved for free use in future harvests.

The alternative to the industrial perspective is the sustainability school of thought, which is emerging and still taking shape, but demonstrating the potential to meet global food needs while better managing some of the environmental and social issues addressed poorly by the industrial food production model. Sustainable agriculture practices call for increasing plant and animal diversity at an agricultural facility so that the outputs from one system (decaying plant matter, animal manure) become the inputs for another in a continual process, negating the need for vast nonrenewable chemical inputs to boost yields. Sustainable agriculture also seeks to restore and improve the ecosystem services that benefit human beings and animals—i.e., water and soil quality—through more natural farming methods like geographically appropriate crop selection, crop rotation and cover crop planting. In essence, in the sustainability model, researchers and practitioners are considering how the carrying capacity of agricultural lands and the overall ecosystem can be rebuilt and possibly improved. An additional key focus of most sustainability advocates is enhancing support for small- and midsized food producers.

Proponents of the industrialized agricultural model claim that the sustainable agriculture concept cannot address the growing food needs of the planet. If current dietary patterns and food consumption rates are maintained, this may indeed be true. However, others argue that reducing discretionary food consumption could allow sustainable agriculture to adequately feed the world. The most obvious way to reduce discretionary consumption is to reduce people’s consumption of inefficient food products, such as processed foods, dairy and meat. Animal products in particular are at the end of a long food chain, each phase of which requires numerous inputs that increase animal products’ input ...