1. Constructive Design Research

iFloor was an interactive floor built between 2002 and 2004 in Aarhus, Denmark. It was a design research project with participants from architecture, design, and computer science. It was successful in many ways: it produced two doctoral theses and about 20 peer-reviewed papers in scientific conferences, and led to other technological studies. In 2004, the project received a national architectural prize from the Danish Design Center.

At the heart of iFloor was an interactive floor built into the main lobby of the city library in Aarhus. Visitors could use mobile phones and computers to send questions to a system that projected them to the floor with a data projector. The system also tracked movement on the floor with a camera. Like the data projector, the camera was mounted into the ceiling. With an algorithm, the system analyzed social action on the floor and sent back this information to the system. If you wanted to get your question brought up in the floor, you had to talk to other people to get help in finding books.

iFloor’s purpose was to bring interaction back to the library. The word “back” here is very meaningful. Information technology may have dramatically improved our access to information, but it has also taken something crucial away from the library experience — social interaction. In the 1990s, a typical visit to the library involved talking to librarians and also other visitors; today a typical visit consists of barely more than ordering a book through the Web, hauling it from a shelf, and loaning it with a machine. Important experience is lost, and serendipity — the wonderful feeling of discovering books you had never heard about while browsing the shelves — has almost been lost.

A blog or a discussion forum was not the solution. After all, interaction in blogs is mediated. Something physical was needed to connect people.

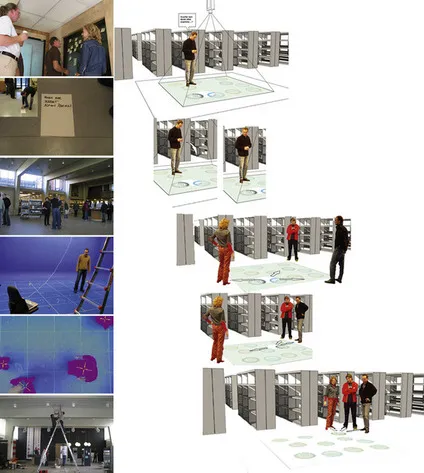

A floor that would do this job was developed at the University of Aarhus through the typical design process. 1 The left row of Figure 1.1 is an image from a summer workshop in 2002, in which the concept was first developed. The second picture is from a bodystorm2 in which the floor’s behaviors were mocked up with a paper prototype to get a better grasp of the proposed idea. Site visits with librarians followed, while technical prototyping took place in a computer science laboratory at the university (left row, pictures 3–5). The system was finally installed in the library (left row, picture at the bottom). How iFloor was supposed to function is illustrated in the computer-generated image on the right side of the picture.

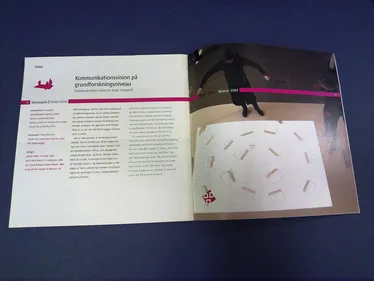

iFloor received lots of media attention; it was introduced to Danish royalty, and it was submitted to the Danish Architecture Prize competition where it was awarded the prize for visionary products (Figure 1.2). In addition, as already mentioned, it was reported to international audiences in several scientific and design conferences.

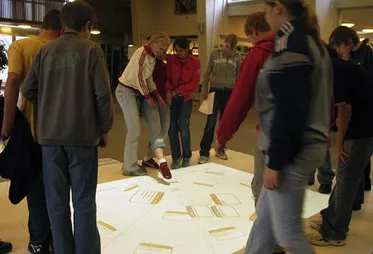

However, only half the research work was done when the system was working in the library. To see how it functioned, researchers stayed in the library for two weeks, observing and videotaping interaction with the floor (Figure 1.3). It was this meticulous attention to how people worked with the iFloor that pushed it beyond mere design. This study produced data that were used in many different ways, not just to make the prototype better, as would have happened in design practice.

Developing the iFloor also led to two doctoral theses: one focusing more on design and technology, another focusing mostly on how people interacted with the floor. 3 Andreas Lykke-Olesen focused on technology, and Martin Ludvigsen’s key papers tried to understand how people noticed the floor, entered it, and how they started conversations while on it. It was this theoretical work that turned iFloor from a design exercise into research that produced knowledge that can be applied elsewhere. In design philosopher Richard Buchanan’s terminology, it was not just a piece of clinical research; it had a hint of basic research. 4

iFloor is a good example of research in which planning and doing, reason, and action are not separate. 5 For researchers, maybe the most important concept iFloor exhibits is that there is value in doing things. When researchers actually construct something, they find problems and discover things that would otherwise go unnoticed. These observations unleash wisdom, countering a typical academic tendency to value thinking and discourse over doing. A PowerPoint presentation or a CAD rendering would not have had this power.

1.1. Beyond Research Through Design

Usually, a research project like iFloor is seen as an example of “research through design.” This term has its origins in a working paper by Christopher Frayling, then the rector of London’s Royal College of Art (RCA) 6. Jodi Forlizzi and John Zimmerman from Carnegie Mellon recently interviewed several experts to find definitions and exemplars of research through design. According to their survey, researchers

make prototypes, products, and models to codify their own understanding of a particular situation and to provide a concrete framing of the problem and a description of a proposed, preferred state…. Designers focus on the creation of artifacts through a process of disciplined imagination, because artifacts they make both reveal and become embodiments of possible futures…. Design researchers can explore new materials and actively participate in intentionally constructing the future, in the form of disciplined imagination, instead of limiting their research to an analysis of the present and the past.7

However, this concept has been criticized for its many problems. Alain Findeli and Wolfgang Jonas, among others, noted that any research needs strong theory to guide practice, but this is missing from Frayling’s paper. 8 For Jonas, Frayling’s definitions remained fuzzy. Readers get few guidelines as to how to proceed and are left to their own devices to muddle through the terrain. Jonas also says that the term provides little guidance for building up a working research practice — and he is no doubt right.

This concept fails to appreciate many things at work behind any successful piece of research. For example, the influential studies of Katja Battarbee and Pieter Desmet made important conceptual and methodological contributions in their respective programs, even though, strictly speaking, they were theoretical and methodological rather than constructive in nature. People read Kees Overbeeke’s writings...