eBook - ePub

Exegetical Gems from Biblical Greek

A Refreshing Guide to Grammar and Interpretation

Merkle, Benjamin L.

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Exegetical Gems from Biblical Greek

A Refreshing Guide to Grammar and Interpretation

Merkle, Benjamin L.

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Learning Greek is a difficult task, and the payoff may not be readily apparent. To demonstrate the insight that knowing Greek grammar can bring, Benjamin Merkle summarizes 35 key Greek grammatical issues and their significance for interpreting the New Testament. This book is perfect for students looking to apply the Greek they have worked so hard to learn as well as for past students who wish to review their Greek.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Exegetical Gems from Biblical Greek est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Exegetical Gems from Biblical Greek par Merkle, Benjamin L. en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Theology & Religion et Biblical Reference. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

Theology & ReligionSous-sujet

Biblical Reference1

Koine Greek

Matthew 18:8

Introduction

It is commonly thought that the most literal translation of the Bible is the best version. In other words, whatever the Greek says should be rendered straightforwardly and without addition or subtraction in the receptor language. But translating the Bible with such a wooden understanding of translation theory is doomed to produce less than ideal results. Because language is complex and ever changing, we must allow for a more nuanced view of how the Bible should be translated. For example, Matthew 18:8 states, “If your hand or your foot causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away. It is better for you to enter life crippled or lame than with two hands or two feet to be thrown into the eternal fire.” The Greek term translated “better” (καλόν) is the positive adjective ordinarily meaning “good.” But is Jesus really stating that it is “good” to enter eternal life maimed or lame?

Overview

In the early part of the twentieth century, it was common for Christians to claim that the Greek of the NT was a special Spirit-inspired Greek and thus different from the typical Greek of the first century. Then scholars compared NT Greek with the Greek found in various papyri of the time and discovered that the NT used the common (colloquial or popular) Greek of the day.1 That is, the Greek of the NT is closer to the language of the ordinary person than to that of the educated person who wrote literature for others to read (e.g., Plutarch).2 And yet the Greek of the NT is still somewhat unique.3 Its uniqueness is probably due to at least two factors. First, the NT authors were heavily influenced by the Septuagint (i.e., the Greek translation of the OT). This influence is seen not only when the Septuagint is quoted but also in the syntax and sentence structure. Second, the NT authors were influenced by the reality of the gospel, and along with that came the need to express themselves in new ways. Machen explains: “They had come under the influence of new convictions of a transforming kind, and those new convictions had their effect in the sphere of language. Common words had to be given new and loftier meanings.”4

The Greek language used during the time of the writing of the NT is known as Koine (common) Greek (300 BC–AD 330). Before this era, the Greek language is known as Classical Greek (800–500 BC) and Ionic-Attic Greek (500–300 BC). Many significant changes occurred in the transition from the Classical/Attic Greek to Koine Greek. Here are some of those changes:

- The increased use of prepositions rather than cases alone to communicate the relationship between words (e.g., Eph. 1:5, προορίσας ἡμᾶς εἰς υἱοθεσίαν διὰ Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ εἰς αὐτόν, κατὰ τὴν εὐδοκίαν τοῦ θελήματος αὐτοῦ, “He predestined us to adoption as sons through Jesus Christ to Himself, according to the kind intention of His will,” NASB), as well as a lack of precision between prepositions (e.g., διά/ἐκ [Rom. 3:30], ἐν/εἰς or περί/ὑπέρ).

- The decreased use of the optative mood (found only 68 times in the NT). Most occurrences are found in formulaic constructions such as μὴ γένοιτο (“May it never be!” NASB; used 14 times by Paul and once by Luke) and εἴη (“could be”; used 11 times by Luke and once by John).

- The spelling change of certain verbs such as first-aorist endings applied to second-aorist verbs (εἶπαν instead of εἶπον, “they said”) and omega-verb endings found on some μι verbs (ἀφίουσιν instead of ἀφιέασιν, “they allow/forgive”).

- The increase of shorter, simpler sentences and as well as the increase of coordinated clauses (parataxis).

And the change that we will focus on in this chapter:

- The increased use of positive and comparative adjective forms used to express a superlative or elative idea.

Interpretation

This last change in Koine helps us understand a number of passages, particularly why they often are not translated “literally.” In Matthew 18:8, is Jesus really stating that it is “good” (καλόν) for someone to enter eternal life maimed or lame? The answer is obviously no, since it is not necessarily “good” for a person to enter eternal life that way, but it is “better” to enter that way than not at all. Thus, here a positive adjective is used in place of a comparative adjective, a common feature in Koine Greek. This interpretation is confirmed by comparing this passage with a similar saying of Jesus earlier in Matthew’s Gospel. In Matthew 5:29–30, συμφέρει (it is profitable, it is better) is used instead of καλόν . . . ἐστίν (it is good).

Another reason we know that the positive adjective can function as a comparative (or superlative) and that a comparative can function as a superlative is that it is fairly common and is sometimes found in contexts where the adjective must function in a way that is different from its “normal” meaning. For example, in Matthew 22:38 we read, αὕτη ἐστὶν ἡ μεγάλη καὶ πρώτη ἐντολή (literally, “This is the great and first commandment”). Although there is not consistency among the English Bible versions in translating this verse, it seems best to translate the positive adjective μεγάλη (great) as a superlative adjective (greatest). This interpretation is derived from the fact that it is one commandment among many (as is confirmed by the use of “first” and “second” in the context). So, for example, the NRSV translates the verse as follows: “This is the greatest and first commandment” (see also CSB, NET, NJB, NLT).5 Another example is found in 1 Corinthians 13:13, where Paul writes, νυνὶ δὲ μένει πίστις, ἐλπίς, ἀγάπη, τὰ τρία ταῦτα· μείζων δὲ τούτων ἡ ἀγάπη, “So now faith, hope, and love abide, these three; but the greatest of these is love.” Here Paul uses the comparative adjective μείζων (greater). The problem, however, is that a comparative adjective is normally used where there are only two entities and one is given a greater degree than the other. So, for example, love is considered greater than faith. But in 1 Corinthians 13:13 Paul offers three concepts: (1) faith, (2) hope, and (3) love. When more than two concepts are compared, a superlative adjective becomes necessary (at least in English). But because Paul uses a comparative adjective when a superlative is typically used, this clearly demonstrates the use of a comparative for a superlative.

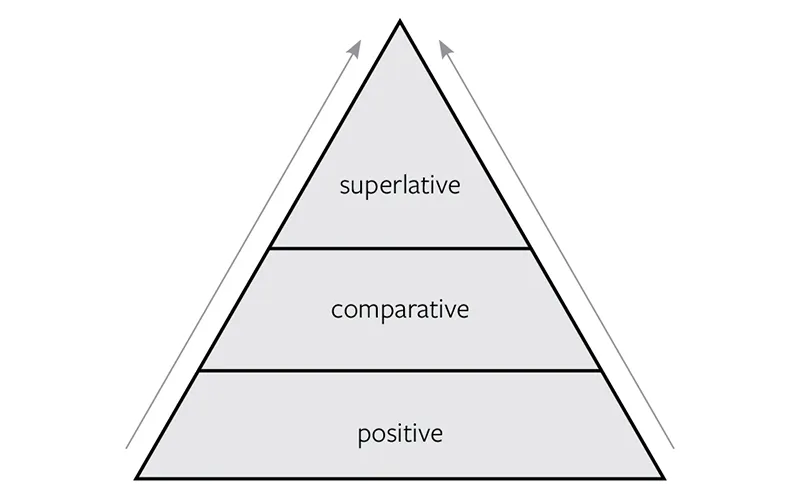

One more item should be mentioned here. It was common for a positive adjective to function as a comparative or superlative and for a comparative adjective to function as a superlative. It was not common, however, for a comparative adjective to function as a positive or for a superlative adjective to function as a comparative or positive. The diagram illustrates that an adjective could perform the function of the adjective degree above it, but not (usually) below it.

1. See esp. Adolf Deissmann, Light from the Ancient East: The New Testament Illustrated by Recently Discovered Texts of the Graeco-Roman World, trans. Lionel R. M. Strachan (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1995; German original 1909).

2. J. Gresham Machen states, “Undoubtedly the language of the New Testament is no artificial language of books, and no Jewish-Greek jargon, but the natural, living language of the period.” New Testament Greek for Beginners (Toronto: Macmillan, 1923), 5.

3. Wallace (28) summarizes, “The style is Semitic, the syntax is conversational/literary Koine (the descendant of Attic), and the vocabulary is vernacular Koine.”

4. Machen, New Testament Greek for Beginners, 5.

5. So also Charles L. Quarles, Matth...