eBook - ePub

Think Like a Mathematician

Get to Grips with the Language of Numbers and Patterns

Anne Rooney

This is a test

Partager le livre

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Think Like a Mathematician

Get to Grips with the Language of Numbers and Patterns

Anne Rooney

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Was mathematics invented or discovered? Why do we have negative numbers? How much math does a pineapple know? Think Like a Mathematician will answer all your burning questions about mathematics, as well as some ones you never thought of asking! Whether you want to know about probability, infinity, or even the possibility of alien life, this book provides a fun and accessible approach to understanding all things mathematics - and more - in the context of everyday life.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Think Like a Mathematician est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Think Like a Mathematician par Anne Rooney en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Mathématiques et Histoire et philosophie des mathématiques. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

MathématiquesCHAPTER 1

You couldn’t make it up – or did we?

Is mathematics just ‘out there’, waiting to be discovered? Or have we made it up entirely?

Whether mathematics is discovered or invented has been debated since the time of the Greek philosopher Pythagoras, in the 5th century BC.

Two positions – if you believe in ‘two’

The first position states that all the laws of mathematics, all the equations we use to describe and predict phenomena, exist independently of human intellect. This means that a triangle is an independent entity and its angles actually do add up to 180°. Mathematics would exist even if humans had never come along, and will continue to exist long after we have gone. The Italian mathematician and astronomer Galileo shared this view, that mathematics is ‘true’.

‘Mathematics is the language in which God has written the universe.’

Galileo Galilei

It’s there, but we can’t quite see it

The Ancient Greek philosopher and mathematician Plato proposed in the early 4th century BC that everything we experience through our senses is an imperfect copy of a theoretical ideal. This means every dog, every tree, every act of charity, is a slightly shabby or limited version of the ideal, ‘essential’ dog, tree or act of charity. As humans, we can’t see the ideals – which Plato called ‘forms’ – but only the examples that we encounter in everyday ‘reality’. The world around us is ever-changing and flawed, but the realm of forms is perfect and unchanging. Mathematics, according to Plato, inhabits the realm of forms.

Although we can’t see the world of forms directly, we can approach it through reason. Plato likened the reality we experience to the shadows cast on the wall of a cave by figures passing in front of a fire.

If you are in the cave, facing the wall (chained up so that you can’t turn around, in Plato’s scenario) the shadows are all you know, so you consider them to be reality. But in fact reality is represented by the figures near the fire and the shadows are a poor substitute. Plato considered mathematics to be part of eternal truth. Mathematical rules are ‘out there’ and can be discovered through reason. They regulate the universe, and our understanding of the universe relies on discovering them.

What if we made it up?

The other main position is that mathematics is the manifestation of our own attempts to understand and describe the world we see around us. In this view, the convention that the angles of a triangle add up to 180° is just that – a convention, like black shoes being considered more formal than mauve shoes. It is a convention because we defined the triangle, we defined the degree (and the idea of the degree), and we probably made up ‘180’, too.

At least if mathematics is made up, there’s less potential to be wrong. Just as we can’t say that ‘tree’ is the wrong word for a tree, we couldn’t say that made-up mathematics is wrong – though bad mathematics might not be up to the job.

‘God created the integers. All the rest is the work of Man.’

Leopold Kronecker (1823–91)

Alien mathematics

Are we the only intelligent beings in the universe? Let’s assume not, at least for a moment (see Chapter 18).

If mathematics is discovered, any aliens of a mathematical bent will discover the same mathematics that we use, which will make communication with them feasible. They might express it differently – using a different number base, for example (see Chapter 4) – but their mathematical system will describe the same rules as ours.

If we make up mathematics, there is no reason at all why any alien intelligence should come up with the same mathematics. Indeed, it would be rather a surprise if they did – perhaps as much of a surprise as if they turned out to speak Chinese, or Akkadian, or killer whale.

For if mathematics is simply a code we use to help us describe and work with the reality we observe, it is similar to language. There is nothing that makes the word ‘tree’ a true signifier for the object that is a tree. Aliens will have a different word for ‘tree’ when they see one. If there is nothing ‘true’ about the elliptical orbit of a planet, or about the mathematics of rocket science, an alien intelligence will probably have seen and described phenomena in very different terms.

How amazing!

Perhaps it is amazing that mathematics is such a good fit for the world around us – or perhaps it is inevitable. The ‘it’s amazing’ argument doesn’t really support either view. If we invented mathematics, we would create something that adequately describes the world around us. If we discovered mathematics, it would obviously be appropriate to the world around us as it would be ‘right’ in a way that is larger than us. Mathematics is ‘so admirably appropriate to the objects of reality’ either because it’s true or because that’s what it was designed for.

How can it be that mathematics, being after all a product of human thought which is independent of experience, is so admirably appropriate to the objects of reality?’

Albert Einstein (1879–1955)

Look out – it’s behind you!

Another possibility is that mathematics seems astonishingly good at representing the real world because we only look at the bits that work. It’s rather like seeing coincidences as evidence of something supernatural going on. Yes, it’s really amazing that you went abroad on holiday to an obscure village in Indonesia and bumped into a friend – but only because you are not thinking about all the times you and other people have gone somewhere and not bumped into anyone you knew. We only remark on the remarkable; unremarkable events go unnoticed. In the same way, no one thinks to fault mathematics because it can’t describe the structure of dreams. So it would be reasonable to collate a list of areas where mathematics fails if we want to assess its level of success.

‘The unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics’

If mathematics is made up, how can we explain the fact that some mathematics, developed without reference to real-world applications, has been found to account for real phenomena often decades or centuries after its formulation?

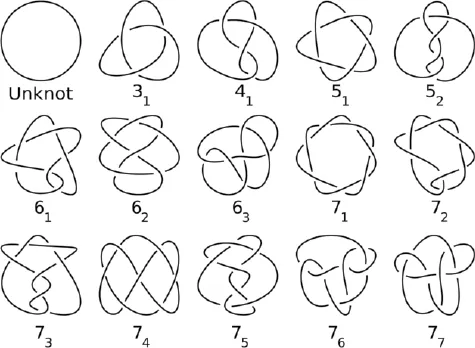

As the Hungarian-American mathematician Eugene Wigner pointed out in 1960, there are many examples of mathematics developed for one purpose – or for no purpose – that have later been found to describe features of the natural world with great accuracy. One example is knot theory. Mathematical knot theory involves the study of complex knot shapes in which the two ends are connected. It was developed in the 1770s, yet is now used to explain how the strands of DNA (the material of inheritance) unzip themselves to duplicate. There are still counter-arguments. We only see what we look for. We choose the things to explain, and choose those that can be explained with the tools we have.

Perhaps evolution has primed us to think mathematically and we can’t help doing so.

Knot theory: the simplest possible true knot is the trefoil or overhand knot, in which the string crosses three times (31 below). There are no knots with fewer crossings. The number of knots increases rapidly thereafter.

‘How do we know that, if we made a theory which focuses its attention on phenomena we disregard and disregards some of the phenomena now commanding our attention, that we could not build another theory which has little in common with the present one but which, nevertheless, explains just as many phenomena as the present theory?’

Reinhard Werner (b.1954)

Does it matter?

If you are just working out your household accounts or checking a restaurant bill, it doesn’t much matter whether mathematics is discovered or invented. We operate within a consistent mathematical system – and it works. So we can, in effect, ‘keep calm and carry on calculating’.

For pure mathematicians, the question is of philosophical rather than practical interest: are they dealing with the greatest mysteries that define the fabric of the universe? Or are they playing a game with a kind of language, trying to write the most elegant and eloquent poems that might describe the universe?

‘The miracle of the appropriateness of the lan...