eBook - ePub

The School Choice Journey

School Vouchers and the Empowerment of Urban Families

T. Stewart,P. Wolf

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

The School Choice Journey

School Vouchers and the Empowerment of Urban Families

T. Stewart,P. Wolf

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

This in-depth chronicle of 110 families in Washington, DC's Opportunity Scholarship Program provides a realistic look at how urban families experience the process of using school choice vouchers and transform from government clients to consumers of education and active citizens.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que The School Choice Journey est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à The School Choice Journey par T. Stewart,P. Wolf en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Education et Educational Policy. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

EducationSous-sujet

Educational Policy1

What Is School Choice, and Why Did Some Parents Choose School Vouchers?

One of the potential by-products of poverty for urban families is a relationship with public agencies that deliver vital supports and services. Families that meet necessary financial eligibility requirements, which often means that household income for the prospective family is at or below the poverty level, can access public-support resources such as child-care assistance, supplemental nutrition programs, and medical services. For example, the US Department of Agriculture’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) provides food stamps that help more than 26 million eligible Americans (of which over 89,000 live in the District of Columbia) to put meals on their tables. Another example is the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, which offers a variety of situational support services to help families facing financial distress navigate the obstacles associated with maintaining a family while working. At the beginning of 2009, TANF had 3,950,357 recipients nationally, including 12,510 within the District of Columbia.1

Although social programs of this type are intended to help reduce the impact of poverty on families, a growing body of research suggests that participation in these programs may have a disempowering effect on individuals who receive their services. Based on mounting evidence, the social programs themselves are not the problem. Instead, the way in which programs are designed and delivered determines whether they produce a positive or negative effect for participants and the upward social mobility of their families.

Some of our deepest insights about the nexus between poverty and school vouchers were sparked by comments made during personal interviews with the OSP participants in the very early stages of the programs. For example, Paula explained the trade-offs low-income families must make as they explore new private school options. She is a native of Washington, DC who graduated from the public school system. She describes school as one of the best experiences of her life. She now has one child in the OSP. When asked how she would compare her parenting style to that of her parents, she explains that, like her parents, she stresses the importance and seriousness of education to her children.

In her second year in the OSP, Paula became increasingly concerned about the quality of the teachers at her child’s school. She is most concerned about the fact that perhaps her child’s private school is not equipped to handle the increased number of OSP students. Though she felt the school was not meeting her daughter’s academic needs, she kept her in the private school primarily to ensure her safety. In addition to her disappointment with the quality of the teachers at the school, Paula was surprised that the class size was no different from the public school they had left. Furthermore, she was disgruntled because she felt she was paying for services that the school had advertised, such as tutoring, but which were not being offered.

While she is considering enrolling her child in a public charter school, Paula remains very concerned about safety. Her advice to parents who are attending or are considering attending private schools through the OSP: conduct surprise or unannounced visits to make sure that the schools are really offering what they advertised. She believes the program is most beneficial if students enroll in elementary school, as opposed to middle or high school. Her greatest concern could be best addressed by establishing a monitoring or accountability system to ensure that private schools that participate in the OSP have both the qualified teachers and the core program features that they advertise to parents.

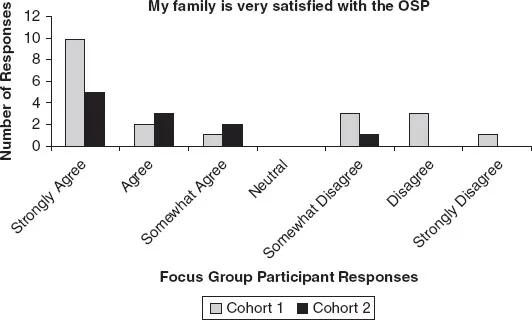

When conducting focus groups with our sample of parent participants in the OSP, the levels of satisfaction with the program they reported also caught our attention. They seemed unusually high for a social program targeting low-income families. During the final stage of our research, we used interactive polling devices to ask parents how successful they thought the OSP had been, and then we compared their responses by year of entry to the program. The respondents were divided into two cohorts based on whether they entered the program in the first year (Cohort 1) or the second year (Cohort 2). Although levels of satisfaction with the OSP were high among both cohorts, satisfaction was somewhat higher among Cohort 2 parents compared to Cohort 1 (see Figure 1.1). It is possible that the truncated implementation schedule for the first year of the OSP prevented program personnel from performing due diligence on the participating schools, thus influencing levels of satisfaction for parents in Cohort 1 such as Paula. Cohort 2 families had more time to learn about the program, apply, and search for placements in schools. Moreover, with a year of implementation behind them, the parents reported that the Washington Scholarship Fund, the entity responsible for managing the day-to-day operation of the program, was more efficient in its administration of the program.

Figure 1.1 Satisfaction with the Opportunity Scholarship Program, 2009

These numbers triggered our curiosity about which aspects of the program were contributing to these high satisfaction levels. We also began to wonder whether the participants’ positive experiences with the OSP were influencing their consumer and citizenship behaviors in distinct ways. We began to examine other bodies of research that explore the nature of the relationship between low-income families and the public agencies that provide housing, health care, and other services, in an attempt to elucidate the relationships that may exist between social program participation and political attitudes and behavior.

The findings from this research challenged us to develop a framework for thinking about the OSP and public schools as social service delivery agents. It became clear from the literature that there are substantial knowledge gaps in our understanding of schools as service delivery organizations. Although previous researchers have identified the existence of links between social program participation and citizenship behavior, very few studies have explored this general topic, and virtually no previous research has examined the family effects of participation in school choice programs. We saw an opportunity, therefore, to use the data generated by our study to contribute to an understanding of how the interaction between program participants and the deliverer of social services can influence the consumer and political attitudes and behaviors of low-income families such as those in a school voucher program.

The framework that we developed is intended for use in exploring how well-designed parental school choice programs can help explain parental satisfaction with programs and can constitute powerful antipoverty tools over and beyond any immediate educational benefits they bestow upon low-income families. They do so by facilitating the development of the skills needed to become more astute consumers and active citizens. The framework can also be used to examine the impacts of other types of social programs on the recipients of their services.

The remainder of this chapter discusses our theoretical framework and uses it to present some of the main relevant findings from our own research and other studies of how social services can have transformative impacts on recipients.

Key Concepts

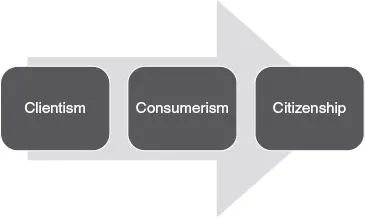

Three key concepts underpin our theoretical framework, all of which have been derived in large part from previous research: “clientism,” “consumerism,” and “citizenship” (see Figure 1.2). These concepts refer to different types of relationships that can exist between public agencies and social program participants. They are each associated with specific attitudes and behaviors on the part of program participants, and they reflect the nature of the relationship between service providers and end users. The arrow in the background represents the general continuum of participant empowerment that is lowest for clients and highest for citizens.

Figure 1.2 Transition from Clientism to Consumerism to Empowered Citizen

The term clientism is used to refer to a relationship where a recipient of a service is easily intimidated by the much larger amount of power, information, and expertise that a service provider appears to have. Public agencies demonstrate a client approach to engaging participants and delivering services when they place a low premium on soliciting input from program participants about their needs and preferences. These agencies often view participating individuals and families as little more than recipients of public services with no control over what they receive or how it is delivered to them. It is well documented in the literature that, for program recipients, the client relationship often involves having to endure demeaning and embarrassing comments and behaviors from service providers.2 At one extreme, this is typified by the relationships between public agencies and the most marginalized or disadvantaged groups in society, such as prison inmates, the homeless, or people struggling with substance abuse. Client relationships also dominate many welfare programs targeting low-income individuals and families, such as food stamps, housing vouchers, and Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), which was a predecessor of TANF.3

We use the term consumerism to connote a more balanced relationship between public service recipients and the agencies charged with providing those services. The conceptualization of public service users as “consumers” has been one aspect of the “New Public Management” paradigm that has become increasingly dominant over the past few decades, as the defining feature of consumerism is choice.4 The extent of choice available and the options for exercising a true consumer relationship in the context of receiving government services have often been limited. Real consumerism entails not just the provision of choices on the part of agencies or service providers but also, most importantly, the ability of the recipient to make well-informed choices. This capability generally assumes that program participants can draw upon relevant knowledge and skills, things which are often lacking among individuals who have had limited exposure to, or experience with, the services in question.5

The third key concept, and the one which is seen as most important in relation to social program participation as an antipoverty tool, is citizenship. This is the most difficult of our three concepts to define in succinct terms because the word has many different meanings.6 For the purpose of the theoretical framework we develop here, citizenship is political participation, defined by Judith Shklar in the following terms:

Good citizenship as political participation . . . applies to the people of a community who are consistently engaged in public affairs. The good democratic citizen is a political agent who takes part regularly in politics locally and nationally, not just on primary and election day. Active citizens keep informed and speak out against public measures that they regard as unjust, unwise, or just too expensive. They also openly support policies that they regard as just and prudent.7

Like consumer behavior, citizenship involves knowledge and skills that often have to be learned or come from experience. We argue, however, that the acquisition of active citizenship-related attitudes and behaviors among low-income adults and families is potentially one of the most powerful ways in which parental school choice initiatives and other social programs can help to lift low-income families out of poverty.

Key Findings of Previous Research

In a democratic society, political participation is the means by which citizens further their own interests and those of the social group or the set of interests that are most important to them. The finite resources available for public spending often mean that this takes—or appears to take—the form of a zero-sum game. As Andrea Campbell observes, “Mass participation influences policy outcomes—the politically active are more likely to achieve their policy goals, often at the expense of the politically quiescent.”8 Within most participating countries in the international Income and Current Election Participation Study, voters were found to have had higher average incomes than non-voters.9 This phenomenon has been attributed at least in part to factors such as the lack of time, money, information, and personal connections among people from low-income backgrounds compared with those of greater means. But there is growing evidence to suggest that the low levels of political participation also result from, and are reinforced by, the design of public policies and the attitudes toward recipients by service providers. As a result, rather than ameliorating poverty and social inequality, public policies and social programs often exacerbate them.

Anne Schneider and Helen Ingram explained this provider paternalism in terms of the ways that the design and delivery of social policies result in the formation of “social constructions” of target populations.10 For example, the intended recipients of such policies are often seen by policy officials and the general public as either “deserving” or “non-deserving,” and either able to take care of themselves or needing active intervention from government in order to do so. Programs such as Social Security and Medicare, which are universally available to all elderly Americans regardless of income, are targeted at people who are seen as deserving of them.11 Most Americans view means-tested government programs, such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) and Medicaid, as being aimed primarily at the “non-deserving,” that is, individuals who have been unable to support themselves and therefore require ...

Table des matières

Normes de citation pour The School Choice Journey

APA 6 Citation

Stewart, T., & Wolf, P. (2016). The School Choice Journey ([edition unavailable]). Palgrave Macmillan US. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3487545/the-school-choice-journey-school-vouchers-and-the-empowerment-of-urban-families-pdf (Original work published 2016)

Chicago Citation

Stewart, T, and P Wolf. (2016) 2016. The School Choice Journey. [Edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan US. https://www.perlego.com/book/3487545/the-school-choice-journey-school-vouchers-and-the-empowerment-of-urban-families-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Stewart, T. and Wolf, P. (2016) The School Choice Journey. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan US. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3487545/the-school-choice-journey-school-vouchers-and-the-empowerment-of-urban-families-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Stewart, T, and P Wolf. The School Choice Journey. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan US, 2016. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.