![]()

Part 1

Theoretical and Implementation

Issues of Content and Language

Integrated Learning

![]()

Chapter 1

Spanish CLIL: Research and

Official Actions

ALMUDENA FERNÁNDEZ FONTECHA

Introduction

Foreign language learning has traditionally been a weak point in Spanish education. The Eurobarometer survey conducted in 2005 on the Europeans’ perceptions about their command of foreign languages reveals that only 36% of the Spanish respondents aged 15 and over replied that they were able to participate in a conversation in a language other than their mother tongue (European Commission, 2005). In other words, despite having received foreign language instruction throughout their schooling years, more than half of the Spanish respondents (64%) only master their mother tongue. The situation is even worse if we take into account that Spanish subjects do not belong to half of the citizens of the member states who can speak at least one language other than their mother tongue at the level of being able to have a conversation. Previous Eurobarometer surveys had not reported better results either (European Commission, 2001a, 2001b).

The current Spanish education is particularly sensitive to European initiatives. Mirroring the European language policy, Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) or bilingual education is nowadays receiving increasing attention in Spanish education. Since the first attempts made to implement the most suitable CLIL models in different European education contexts, many lines have been written on this educational approach, many meetings of CLIL experts have taken place and a large number of conferences and workshops have been held across Europe. In the current CLIL literature, we find references of different origins. In the Canadian and American versions of CLIL, we should mention the works by Brinton et al. (2004), Cantoni-Harvey (1987), Celce-Murcia (1991) or Mohan (1986). In the European context, we should note, among others, the works by Dalton-Puffer and Smit (2007), Fruhauf et al. (1996), Marsh (2002), Marsh et al. (2001) and the Eurydice survey (Eurydice, 2006), which describes the state of the art of European CLIL experiences. Mohan et al. (2001) describe the situation in countries such as Canada, England and Australia.

The main purpose of this chapter is to provide a up to date account of two different but interrelated issues of CLIL, namely, (1) the research conducted on Spanish CLIL or bilingual education both in bilingual and monolingual communities, and (2) the recent official Spanish initiatives that promote bilingual education or that include a CLIL approach to L2 learning at non-university levels in Spanish monolingual communities. Throughout this account, particular emphasis is placed on examining the situation in monolingual communities because they have been traditionally forgotten in bilingual education literature.

The Spanish Linguistic Map

Spain is a mixture of heterogeneous language situations that lead to different ways of understanding and managing L2 education. Its territorial organization is based on a system of autonomous communities. Apart from Spanish, some of these communities own another official language. This peculiarity gives way to language contact situations that enable a culture of bilingualism non-existent in the rest of the communities where Spanish is the only official language.

Spain is divided into 17 autonomous self-governing communities, further split into 50 provinces, and Ceuta and Melilla, two autonomous cities located in the north of Africa. In 1978, the language policy was made explicit in the Spanish Constitution through the following three points: (1) ‘Castilian (also called Spanish) is the official Spanish language of the State; all Spaniards have the duty to know it and the right to use it’; (2) ‘the other Spanish languages shall also be official in the respective self-governing communities in accordance with their Statutes’; and (3) ‘the richness of the different linguistic modalities of Spain is a cultural heritage which shall be specially respected and protected’.1 This provides us with the basis for better understanding the linguistic richness within the Spanish context, namely, Spanish is the only official language throughout the entire Spanish state; however, in some communities it shares that official status with other languages particular to those communities.

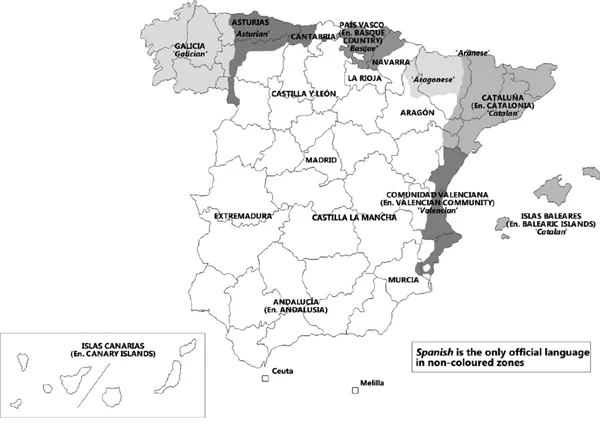

The latter is the case of Basque in the Basque Autonomous Community (BAC)2; Catalan mainly in Catalonia, although a variety of it is spoken in the Valencian Community and the Balearic Islands; Valencian in Valencia, and Galician in Galicia.3 The speakers of these languages make up 13 million people, almost 34% of the Spanish population (Turell, 2001). However, from a sociolinguistic approach, the Spanish linguistic map may become more complex. This approach includes aspects such as the language’s official status, its presence in the media, learners’ knowledge and use, its social prestige and presence in teaching, among others (Burgueño, 2002). Besides, the complexity of this picture increases if we take into account the new migrant minorities. From being traditionally a migrant country, in the last two decades Spain has become a permanent destination for many people. Figure 1.1 displays a simplified version of the current Spanish linguistic map.

Figure 1.1 Simplified version of the Spanish linguistic map. Adapted from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Spain_languages.png (retrieved 25 February 2008)

Research on Spanish bilingual education

Bilingual communities

The linguistic situation in Spanish bilingual communities is the usual scenario for research done on bilingualism, multilingualism and bilingual or multilingual education (e.g. Huguet, 2004; Huguet et al., 2008; Pérez-Vidal et al., 2007). A large body of literature is found on aspects of bilingualism and multilingualism not necessarily linked to education (Hoffmann, 1995; Siguán, 1992, 1994, 2007; Turell, 2001). Far from being a homogeneous phenomenon, Spanish bilingual education is a many-sided issue: different bilingual instructional models are designed that depend on the particularities of each area. Spanish education is decentralized and educational powers are transferred to the autonomous communities. This fact gives rise to a great deal of variation in the educational plans devised by each community. For an updated account of the particularities of Spanish bilingual education, see Rodríguez–Yáñez et al. (2005) and Turell (2001).

The Basque Country and Catalonia are two main exponents of a multilingual awareness-raising process in Spain. In recent years, a large number of language research groups have proliferated in both contexts. The REAL Group (Research in English Applied Linguistics), which has obtained the status of ‘Consolidated Research Group’ granted by the Basque Government, covers a great deal of the research done in the Basque Country. On the other hand, the research conducted in Catalonia is shared by different groups. Some of the most prolific are the BCN-SLA Research Team, coordinated by Carmen Muñoz; AICLE-CLIL BCN European Project, coordinated by Carmen Muñoz and Teresa Navés; the consolidated group ALLENCAM (Language Acquisition from Multilingual Catalonia), coordinated by Carmen Pérez-Vidal; Grupo de investigación sobre plurilingüismo, interculturalidad y educación, coordinated by Ángel Huguet; the GREIP research group (Grup de Recerca en Ensenyament i Interacció Plurilingües), coordinated by Lucila Nussbaum Capdevila or the CLIL-SI research group (Semiimersió en Llengua Estrangera a L’aula Inclusiva), which have developed the ArtICLE project (Avaluació de tasques col·laboratives i assoliment d’objectius d’aprenentatge en aules ‘AICLE’), and is currently working on the MFP project (Model de Formació del Professorat), both coordinated by Cristina Escobar Urmeneta. The research production of these groups is so extensive that to provide a full account of it and its results is completely out of the scope of this chapter. Instead, the following lines are but a representative sample of the variety of works published by them and other researchers in these communities.

Among the contributions on bilingualism and multilingualism in the Basque Country, we find studies dealing with the age factor and its relation to foreign language learning within bilingual communities (García Mayo & García Lecumberri, 2003; Ruiz de Zarobe, 2005), studies on different aspects of trilingual education such as Almgren and Idiazabal (2001), Cenoz (1998, 2001, 2003, 2005), Cenoz and Valencia (1994), Gallardo del Puerto (2005) and García Mayo and Lázaro (2005). Many studies by Lasagabaster (2000, 2001) are on aspects related to the educational system in the Basque Country, and to attitudes towards any of the languages learned (Lasagabaster, 2004, 2005, 2007).

Some recent studies by this research group have focused on assessing CLIL and non-CLIL learners’ proficiency in specific L2 areas. Although in most cases the results indicate no substantial differences in the performance of CLIL and non-CLIL students, in general, when some differences are detected, the results seem to be slightly better for the group of CLIL learners. In these studies, the CLIL and non-CLIL groups consist of Spanish/Basque bilingual secondary learners of L3 English. Both groups had started their exposure to English at eight years of age; however, the CLIL group had received some additional exposure to English as L3. The most favourable results are those obtained by Martínez and Gutiérrez (in this volume), who investigated morpho-syntactical aspects. The CLIL learners outperform the non-CLIL learners only partially in the research conducted by Villarreal and García Mayo (in this volume) on the acquisition of tense and agreement morphology. Finally, Gallardo del Puerto et al. (in this volume) find no significant differences between the two groups of CLIL and non-CLIL learners concerning the acquisition of pronunciation.

As in the Basque Country, in Catalonia, many research projects are devoted to bilingual and trilingual education, such as Muñoz (2000) and Navés et al. (2005). Bosch and Sebastián-Gallés (2001) examine Jürgen Meisel’s Differentiation Hypothesis in the case of young Catalan-Spanish bilinguals. Besides, Catalan linguistic immersion is analysed in different publications, such as the pioneering work by Artigal (1991) or the recent work by Serra (2006). Moreover, we find comprehensive works dealing with both cases of Catalan and Basque immersion, such as Artigal (1993) and Huguet (2004), who discusses the legal bases and social context for language learning in both contexts. As in the Basque case, some authors in this context refer to affective factors. Bernaus et al. (2007) analyse the influence of the affective factors that influence plurilingual students’ acquisition of Catalan in that bilingual context. In addition, in Catalonia, we find pioneering CLIL-specific contributions, such as Navés and Muñoz (1999), Pérez-Vidal (1998, 1999, 2001) or Scott-Tennent (1993, 1994–1995, 1996). Part of these publications addresses practical aspects of CLIL implementation (Escobar, 2007; Escobar & Pérez Vidal, 2004; Pérez-Vidal, 1997; Pérez-Vidal & Campanale Grilloni, 2006).

Research on bilingual education in other communities with more than one official language has received less attention, but some studies can be found: for instance, Cajilde (1991) and Marco (1993) focus on Galician. On Valencian, there is a wide variety of works dealing with these topics. To mention just a few, there is Safont’s (2005) discussion on sociolinguistic aspects of language learning and use in the Valencian community, the research conducted by Blas (2002) referring to the Valencian educational system and the community’s language policy and Baldaquí’s (2000) doctoral dissertation on bilingual education programmes in the province of Alicante. The case of the autonomous community of Navarra presents quite a complex linguistic situation, which is described in Actas de las Jornadas de Lenguas Extranjeras (Gobierno de Navarra, 1999).

Some research has also been conducted in communities affected by some type of linguistic contact between languages that are not necessarily official. This is the case of Aragonese in the north of Aragón (Broc et al., 1994; Huguet, 1994; Huguet & González, 2003; Janés & Huguet, 2000). Fewer studies can be found concerning multilingual education in these communities with a language contact situation, an example of which is the work by Huguet et al. (2004) who describes a model of trilingual education in the Aran Valley.

Monolingual communities

As regards the monolingual communities, fewer studies are found. We shall consider the research conducted in at least two of these communities: Madrid and La Rioja.

In Madrid, we should address the research carried out by a team of professionals at the University of Alcalá. Their work focuses on bilingual education in primary schools of their community. So far, this research has mostly explored teacher-related issues, such as teachers’ expectations and teacher training (Fernández et al., 2005; Halbach et al., 2005; Pena et al., 2006). In the same community, Martín White and Cercadillo (2005) present a project carried out during three school years in a comprehensive secondary school, where geography and history curricula are taught in English. Furthermore, Llinares and Whittaker (2006) conduct their research on oral and written production of CLIL secondary students of social science in English. Overall, they are obtaining promising results. In the same context, we should include the work by Dafouz (2006) on the teacher’s use of pronouns and modal verbs in a CLIL university level.

In La Rioja, Rosa María Jiménez Catalán coordinates the Applied Linguistics research group GLAUR (Grupo de Lingüística Aplicada de la Universid...