![]()

1

The Real World of Torts

At 7:34 a.m. on September 22, 1989, twenty-one middle school and high school students in Alton, Texas, died and forty-nine others were injured when their school bus collided with a Coca-Cola delivery truck, fell twenty-four feet into a gravel pit, and was submerged in water. The National Transportation and Safety Board investigation found that each of the students died as a result of “drowning or complications related to the submersion” and that “the probable cause of the accident was the truckdriver’s inattention and subsequent failure to maintain sufficient control of his vehicle to stop at [a] stop sign. Contributing to the severity of the accident was the lack of a sufficient number of emergency exits on the school bus to accommodate the rapid egress of all . . . students.”1

Like most tort plaintiffs, the parents of the victims did not immediately turn their thoughts toward tort lawsuits. “‘I didn’t want a lawyer,’ said Carmen Cruz, whose 17-year-old daughter was killed in the crash and whose 14-year-old daughter was injured. ‘I said, “The first lawyer who can bring my daughter back, I’ll hire.”’”2 But lawsuits were eventually filed—lawsuits involving allegations about the negligence of the truck driver, the poor design of the school bus, the dangerousness of the intersection, and the lack of guard rails near the pit.3 Like most lawsuits, the cases ultimately settled.4

Social scientists have studied how disputes, including those like this tragic bus accident (which inspired the movie The Sweet Hereafter), arise and are pursued. Popular images of tort plaintiffs suggest that people sue over any small injury, no matter whose fault it is. And torts casebooks can give the impression that most tort disputes are resolved through trial (if not on appeal). But one of the striking discoveries of the real world of torts is that most people “lump it” rather than sue.

The starting point of a potential tort case is the experience of an injury, and it is easy to see how a psychological perspective is inherent in this experience. But the transformation of an injury into a tort claim involves multiple stages, each also involving psychology. For an injury to become a dispute, an injured party must first recognize that she has been injured—a process of naming. Next, she must attribute the source of the harm to the fault of another—blaming. And then she must approach that other to ask for reparation of some kind—claiming a need for redress. Only when such a request has been in some way denied does a dispute emerge.5 And, as we will see, only some of these disputes will formally make their way into the tort system.

The Pattern of Tort Disputes

The Real Worlds of Torts

As we describe the real world of torts, it is worth noting that tort cases do not constitute a single, monolithic world. Instead, the tort system consists of several worlds.6 Automobile accidents make up the biggest category of tort cases, accounting for almost 60 percent of tort trials. These cases tend to involve more routinized claiming processes, often through insurance companies. Perhaps as a result, these cases tend to have higher rates of claiming and are less likely to involve lawyers. These cases also tend to involve fairly modest claims and to have higher plaintiff win rates in comparison to other types of cases.7 In contrast, high-stakes medical malpractice or products liability claims involve more complex issues, are more expensive to bring to trial, have lower rates of claiming and lower plaintiff win rates, and tend to result in higher awards.8 Mass torts make up yet another distinct world of tort litigation, one that involves class actions and multidistrict litigation, difficult issues of law and fact, and particular tension between the efficient resolution of cases and individualized justice (see chapter 8).9 There is, of course, additional variation among cases within each of these worlds, but paying attention to these broad categories helps to highlight the different ways that distinct types of cases tend to make their way through the system.

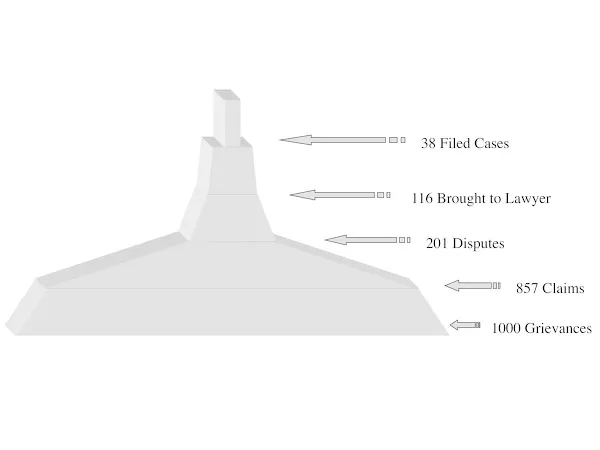

The Disputing Pyramid

As cases evolve from injuries to formal tort cases, there is a significant amount of attrition—many cases fall away at each stage. Social scientific research suggests that the pattern of tort disputes resembles a pyramid, which starts from a baseline set of grievances and shows increasing attrition as cases develop into claims, disputes, and formal legal matters, with cases dropping out of the system as they are abandoned or settled. In a classic study using data collected as part of the Civil Litigation Research Project in 1980, Richard Miller and Austin Sarat estimated that for every 1,000 grievances, only about 200 became disputes, only 116 made their way to a lawyer, and only 38 (fewer than 4 percent of grievances and fewer than 19 percent of disputes) became formal filed cases (see figure 1.1).10 More recent data—primarily in specialized contexts such as medical malpractice11 or from countries other than the United States12—corroborate this pattern of significant attrition and few filed cases. In short, lumping it is the norm.

Why might this pattern of attrition occur? A psychological perspective offers some explanations. First, some injuries are not identified as injuries by those who are injured. An injury might be too minor to be noticed. Its effects might not be discernible until some later point in time. It might be difficult to distinguish from symptoms that are not considered injurious (“Is this pain a normal effect of my surgery or was I injured in some unexpected way?”).13