![]()

Early Detection of Psychosis: Clinical Assessments

Riecher-Rössler A, McGorry PD (eds): Early Detection and Intervention in Psychosis: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Key Issues Ment Health. Basel, Karger, 2016, vol 181, pp 29-41 (DOI: 10.1159/000440912)

______________________

First Signs of Emerging Psychosis

Frauke Schultze-Lutter

University Hospital of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

______________________

Abstract

The majority of first-episode psychoses are preceded by a prodromal phase that is several years on average, frequently leads to some decline in psychosocial functioning and offers the opportunity for early detection within the framework of an indicated prevention. To this, two approaches are currently mainly followed. The ultra-high-risk (UHR) criteria were explicitly developed to predict first-episode psychosis within 12 months, and indeed the majority of conversions in clinical UHR samples seem to occur within the first 12 months of initial assessment. Their main criterion, the attenuated psychotic symptoms criterion, captures symptoms that resemble positive symptoms of psychosis (i.e. delusions, hallucinations and formal thought disorders) with the exception that some level of insight is still maintained, and these frequently compromise functioning already. In contrast, the basic symptom criteria try to catch patients at increased risk of psychoses at the earliest possible time, i.e. ideally when only the first subtle disturbances in information processing have developed that are experienced with full insight and do not yet overload the person's coping abilities, and thus have not yet resulted in any functional decline. First results from prospective studies not only support this view, but indicate that the combination of both approaches might be a more favorable way to increase sensitivity and detect risk earlier, as well as to establish a change-sensitive risk stratification approach.

© 2016 S. Karger AG, Basel

The idea to detect psychosis early, desirably even before the onset of the first frank psychotic episode, goes far back. As early as 1932, the German psychiatrist Wilhelm Mayer-Gross (1889-1961), an important member of the ‘Heidelberg school’ of psychopathology until his emigration to the UK in 1933, wondered ‘why hitherto one has so infrequently made use of the impressive experience that is represented by the first irruption of a thought disorder, a decrease in activity, an aberration in sympathy and other emotions into the healthy personality’ [1, p. 296; translation by the author] of persons with emerging psychosis. His detailed and illustrated description of the subtle first symptoms of an insidious onset was one of the first comprehensive descriptions of prodromal symptoms of first-episode psychosis and a main source of inspiration for the subsequent works of Gerd Huber (1921-2012), i.e. for the development of the concept of basic symptoms [2-4].

The Concept of Basic Symptoms

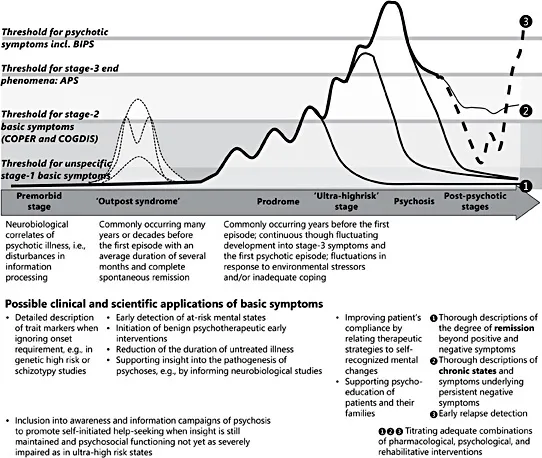

Starting in the 1960s, Gerd Huber gradually developed the concept of basic symptoms from two different lines of his work [2]: from the detailed psychopathological reconstruction of the development of first-episode schizophrenia and its subsequent course in the Bonn Schizophrenia Study [5], and from his pioneer pneumoencephalographic study showing enlarged third ventricles in schizophrenic patients [6, 7]. In presumption of two main aspects of the basic symptom concept, Mayer-Gross [1] had already conceptually distinguished between first uncharacteristic (e.g. lack of motivation and obsessive-compulsive phenomena) and first characteristic signs of developing schizophrenia (e.g. subtle disturbances in thinking, salience, affect and interpersonal relatedness). Moreover, he considered these early symptoms not as part of the premorbid personality that - equal to basic symptoms - would be present ‘already pre-psychotically but precisely not pre-morbidly’ [2, p.134; translated by the author; italics as in original]. Against this background, Huber [2, 8] later introduced the term ‘substrate-close basic symptoms’ to delineate his conviction that these early and often initially occurring subjective symptoms would form the basis for the development of psychotic ‘end phenomena’ and be the most immediate reportable self-experience of the somatic processes underlying the illness, i.e. disturbances in cortical information processing. Therefore, Huber regarded basic symptoms as ‘micro-productive positive symptoms in statu nascendi’ [2, p.135; translated by the author; italics as in original] that had a closer association to neurobiological aberrations than positive psychotic and also negative symptoms [2, 8] (fig. 1). This assumption was recently supported by a functional magnetic resonance imaging study [9] that provided evidence for a cortical link between basic symptoms but not positive, negative or general symptoms and social cognition in first-episode schizophrenia. Aberrant functional interactions of the right ventral premotor cortex and bilateral posterior insula with the posterior cingulate cortex positively correlated with the total score of basic symptoms assessed with the Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument, Adult version (SPI-A) [10], but not with the any of the subscale totals of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [11]. The authors suggested that this dysfunction might be closely related to basic symptoms and might help to disentangle the cortical basis of how self-experienced disturbances, i.e. basic symptoms, may effect social functioning [9].

Basic symptoms usually do not develop continuously and linearly into psychotic symptoms, but rather fluctuate in their appearance and severity, i.e. alternate between uncharacteristic ‘stage 1’ and more characteristic ‘stage 2’ basic symptoms as well as diagnostically subthreshold ‘stage 3’ symptoms [2, 12]. They might as well spontaneously remit completely, thus not strictly being part of a prodrome but rather of an ‘outpost syndrome’ (fig. 1). These symptom fluctuations are in response to endogenous factors as well as to situational factors such as daily stressors or even minimal affective arousal [2, 12]. Insufficient coping, including the development of inadequate explanatory models, then eventually leads to the development of stage 3 ‘end phenomena’, i.e. attenuated and frank psychotic symptoms. Basic symptoms and initiation of inadequate or lack of coping strategies for these also trigger negative symptoms such as withdrawal in response to a self-perceived decreased stress tolerance or desire for social contacts or even as a reaction to cognitive disturbances possibly impairing communication skills [2, 12].

Fig. 1. Model of the development and course of psychosis according to the basic symptom concept and possible applications of basic symptoms in different illness stages [13, 14].

Basic symptoms can be assessed by trained clinicians in a thorough clinical interview in all stages of psychotic disorders, and can thus serve multiple clinical and scientific purposes (fig. 1) [13]. However, their perception and assessment might be severely impaired by the loss of insight and of reality testing that commonly characterizes the acute psychotic episode [3, 4, 10, 14].

General Characteristics of Basic Symptoms

An obligate characteristic of basic symptoms is their subjectivity, i.e. their experience and report as disturbances or aberrations from ‘normal’ fluctuations in mental state known from the premorbid phase by patients themselves [10, 12-15]. Experienced with full insight, basic symptoms are thereby immediately recognized as dysfunctions in mental processes and not projected into the environment. As a result, basic symptoms either might be qualitatively new (in terms of a state marker) or might significantly increase in frequency while decreasing in their association to situational triggers at the same time (in terms of a trait-state marker). Consequently, phenomena that have clearly been present throughout life in the same severity or frequency (in terms of a trait marker) would not be considered basic symptoms by definition [3, 10, 13, 14], although they can be scored as a trait characteristic in both the SPI-A and the Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument, Child and Youth version (SPI-CY) [14].

Despite their conception as a direct expression of the underlying neurobiological dysfunction, a diagnosed neurological or another somatic disorder that might account for the disturbance is an exclusion criterion of basic symptoms. Further, phenomena that result from psychotropic substance use or that are a side effect of (psycho-)pharmacological medication are not considered basic symptoms [10, 14]. When these exclusion criteria were deliberately ignored, basic symptoms were reported to a degree similar to that of psychotic patients and clinical high-risk patients with later development of psychosis by patients with organic mental disorder [16] and patients with substance misuse, in particular of ketamine and cannabis [17], respectively.

Basic Symptoms in the Early Detection of First-Episode Psychosis

In the first long-term prospective early detection study, the Cologne Early Recognition (CER) study [18, 19], the predictive utility of basic symptoms was ...