![]()

Chapter 1

Preliminaries

It is commonly believed that more than 70% (!) of the effort and cost of developing a complex software system is devoted, in one way or another, to error correcting.

Algorith., pg. 107 [Harel (1987)]

1.1What is correctness?

To show that an algorithm is correct, we must show somehow that it does what it is supposed to do. The difficulty is that the algorithm unfolds in time, and it is tricky to work with a variable number of steps, i.e., while-loops. We are going to introduce a framework for proving algorithm (and program) correctness that is called Hoare’s logic. This framework uses induction and invariance (see Section 9.1), and logic (see Section 9.4) but we are going to use it informally. For a formal example see Section 9.4.4.

We make two assertions, called the pre-condition and the post-condition; by correctness we mean that whenever the pre-condition holds before the algorithm executes, the post-condition will hold after it executes. By termination we mean that whenever the pre-condition holds, the algorithm will stop running after finitely many steps. Correctness without termination is called partial correctness, and correctness per se is partial correctness with termination. All this terminology is there to connect a given problem with some algorithm that purports to solve it. Hence we pick the pre and post condition in a way that reflects this relationship and proves it true.

These concepts can be made more precise, but we need to introduce some standard notation: Boolean connectives: ∧ is “and,” ∨ is “or” and ¬ is “not.” We also use → as Boolean implication, i.e., x → y is logically equivalent to ¬x ∨ y, and ↔ is Boolean equivalence, and α ↔ β expresses ((α → β) ∧ (β →α)). ∀ is the “for-all” universal quantifier, and ∃ is the “there exists” existential quantifier. We use “⇒” to abbreviate the word “implies,” i.e., 2|x ⇒ x is even, while “⇏” abbreviates “does not imply.”

Let

A be an algorithm, and let

be the set of all

well-formed inputs for

A; the idea is that if

I ∈

then it “makes sense” to give

I as an input to

A. The concept of a “well-formed” input can also be made precise, but it is enough to rely on our intuitive understanding—for example, an algorithm that takes a pair of integers as input will not be “fed” a matrix. Let

O =

A(

I) be the output of

A on

I, if it exists. Let

αA be a precondition and

βA a post-condition of

A; if

I satisfies the pre-condition we write

αA(

I) and if

O satisfies the post-condition we write

βA(

O). Then, partial correctness of

A with respect to pre-condition

αA and post-condition

βA can be stated as:

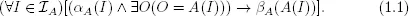

In words: for any well formed input I, if I satisfies the pre-condition and A(I) produces an output (i.e., terminates), then this output satisfies the post-condition.

Full correctness is (1.1) together with the assertion that for all

I ∈

,

A(

I) terminates (and hence there exists an

O such that

O =

A(

I)).

Problem 1.1. Modify (1.1) to express full correctness.

A fundamental notion in the analysis of algorithms is that of a loop invariant; it is an assertion that stays true after each execution of a “while” (or “for”) loop. Coming up with the right assertion, and proving it, is a creative endeavor. If the algorithm terminates, the loop invariant is an assertion that helps to prove the implication αA(I) → βA(A(I)).

Once the loop invariant has been shown to hold, it is used for proving partial correctness of the algorithm. So the criterion for selecting a loop invariant is that it helps in proving the post-condition. In general many different loop invariants (and for that matter pre and post-conditions) may yield a desirable proof of correctness; the art of the analysis of algorithms consists in selecting them judiciously. We usually need induction to prove that a chosen loop invariant holds after each iteration of a loop, and usually we also need the pre-condition as an assumption in this proof.

1.1.1Complexity

Given an algorithm

and an input

x, the running time of

on

x is the number of steps it takes

to terminate on input

x. The delicate issue here is to define a “step,” but we are going to be informal about it: we assume a Random Access Machine (a machine that can access memory cells in a single step), and we assume that an assignment of the type

x ← y is a single step, and so are arithmetical operations, and the testing of Boolean expressions (such as

x ≥ y ∧

y ≥ 0). Of course this simplification does not reflect the true state of affairs if for example we manipulate numbers of 4,000 bits (as in the case of cryptographic algorithms). But then we redefine steps appropriately to the context.

We are interested in worst-case complexity. That...