Biological Sciences

Algal Blooms

Algal blooms are rapid increases in the population of algae in aquatic ecosystems. These blooms can be caused by factors such as nutrient pollution, warm temperatures, and calm water conditions. While some algal blooms are harmless, others can produce toxins that are harmful to humans and wildlife, leading to water quality issues and ecological imbalances.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Algal Blooms"

- Ramesh Sivanpillai, John F. Shroder(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Elsevier(Publisher)

2.1. Introduction

Blooms are dense accumulations of microscopic algal or cyanobacterial cells within marine, brackish, and freshwater bodies, often resulting in visible discoloration of the water (Heisler et al., 2008 ). Most blooms are caused by planktonic algae that float in the water, but occasionally the term may describe accumulations of microscopic benthic algae or macroalgae, which grow attached to surfaces (Box 2.1 ). Phytoplankton blooms in coastal areas may colloquially be referred to as “red tides.” Many algal species bloom as a part of their seasonal periodicity, but some algae produce toxins which are harmful to humans and other animals. The impacts of algal toxins on humans can be direct in the case of toxic exposure, resulting in death to relatively mild illness, or may arise from long-term chronic exposure, although causal links have yet to be conclusively proven (Ueno et al., 1996 ; Carmichael et al., 2001 ). Some Algal Blooms are also linked to the death and illness of livestock, pets, birds, and marine animals through direct toxicity or major disruption of ecological conditions. Together, blooms which cause harm to humans or other organisms are termed harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) (Table 2.1 ).Box 2.1 Hidden Hazards of SeaweedsDeadly concentrations of hydrogen sulphide gas emitted from thick decomposing strandlines of the seaweed Ulva spp. on a beach in Brittany were linked to the death of a horse, which became stuck in the algal sludge. A man accompanying the horse was left seriously ill. The incident occurred in 2009, but previously on the same beach an unexplained death of a man and the recovery of a man who lapsed into a coma, were each associated with similar bloom occurrences. The deaths of two dogs on a nearby beach were similarly associated with blankets of rotting Ulva . The cause of the increased blooms along the Britany coast has been linked to intensive pig farming in the area, which has increased the discharge of nitrates into the sea. Other high-profile incidents involving blooms of marine macro-algae and linked to eutrophication include the major clean-up operation to remove an Enteromorpha- eBook - PDF

Coastal Pollution

Effects on Living Resources and Humans

- Carl J. Sindermann(Author)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

57 5 Harmful Algal Blooms in Coastal Waters INTRODUCTION: Algal Blooms AND ALGAL TOXICITY Algal Blooms and algal toxicity are natural phenomena. Why, then, should they have a dominant position in a book concerned with coastal pollution? Two good reasons are: (1) augmentation of levels of nitrogen and phosphorous in coastal/estuarine waters — the basis for explosive population growth of planktonic algae — has been shown in many instances to be of human origin, and (2) human transport of toxic algal species to new habitats — with ships’ ballast water and by other commercial practices — has been demonstrated and is undoubtedly of common occurrence. The frequency of occurrence, areal extent, and intensity of Algal Blooms seems to be increasing on a global scale — a trend that would be expected as a consequence of human contributions of nutrient chemicals to coastal/estuarine waters and of human participation in disseminating alien species. Additionally, the list of types of algal toxins is gradually expanding, as is the geographic extent of reported toxic events and knowledge about the nature of the toxins produced. Population explosions of planktonic unicellular algae — so-called “Algal Blooms” or “red tides” (even though many of them are not red) have been observed for centuries and have in some instances caused shellfish in areas such as Puget Sound and northern New England to become temporarily toxic to humans. Paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) is the best-known consequence of eating toxic bivalve molluscs, although several other types of poisoning have been described, and new ones are being identified. Not all blooms are toxic, but many that are not may still be harmful in a variety of ways — for example by reducing light penetration, by reducing dissolved oxygen levels, by forming mucilaginous aggregates, or by inter-fering with respiration of fish. - eBook - PDF

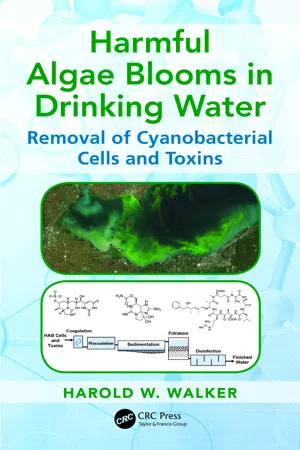

Harmful Algae Blooms in Drinking Water

Removal of Cyanobacterial Cells and Toxins

- Harold W. Walker(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

In China, some studies sug-gested a connection between a higher incidence of liver cancer and drinking water contaminated with cyanotoxins. 2.4 Ecology of Harmful Algal Blooms The occurrence of HABs is controlled by a variety of physical, chemical, and biological factors. Eutrophication is the driving force that leads to the for-mation of Algal Blooms. Eutrophication is the enrichment of a water body with certain nutrients, most typically nitrogen and phosphorus [8]. Although eutrophication promotes algae growth, the predominance of particular algal species is more nuanced. The factors that may influence the proliferation of a particular harmful algal species in a given aquatic system may be unique, with different freshwater HAB species responding to a different set of condi-tions. In Lake Erie, for example, eutrophication caused by phosphorus led to thick mats of cyanobacteria ( Anabaena , Aphanizomenon , and Microcystis ) and the filamentous green alga Cladophora [9] in the 1960s and 1970s. As a result, extensive research was carried out that ultimately led to limits on phosphorus inputs from point sources such as sewage treatment plants. The point source limits on phosphorus were successful in reducing phospho-rus inputs to the lake. In fact, the corresponding reduction in phosphorus to the lake all but eliminated Algal Blooms by the 1980s. In the mid-1990s, however, significant blooms of cyanobacteria ( Microcystis and Lyngbya ) and 15 Occurrence and Ecology of Harmful Algal Blooms green alga ( Cladophora ) began to appear in Lake Erie. The first massive bloom of Microcystis occurred in 2003, and similar blooms have occurred each year since. To understand these changes in the distribution of algal species and mag-nitude of Algal Blooms, it is important to define the different operational forms of phosphorus. One measure of phosphorus in natural aquatic sys-tems is total phosphorus , which represents the sum of dissolved phosphorus and particulate phosphorus. - Khanna, D R(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Biotech(Publisher)

The identification of algae is very difficult for they display few characters and due to their short generation time rate of evolution is higher resulting in several sibling species. There are about 30,000-40,000 species of algae (Andersen, 1992; John 1994) and BGA constitute 150 genera and 2000 species (Hoek et al ., 1995). Blue-Green Algae Decreasing Freshwater Biodiversity Human activities like agricultural runoff, inadequate sewage treatment, runoff from roads have led to excessive fertilization of many water bodies which is more commonly termed as: Eutrophication. Eutrophication promotes the excessive proliferation of the BGA and inter alia the Biologically Available Phosphorus (BAP) is the chief factor (Schindler, 1977). The factors decreasing freshwater biodiversity caused by some BGA, which is paradoxically the lifeline of the same ecosystem, are mainly of two types: the toxins produced by some microalgae and production of high biomass or bloom formation. The problems associated with biomass blooms and toxic events are different. The dynamics of bloom formation varies from place to place, not depending alone of the hydrographic and topographical conditions, but also on ecological and biological characteristic of the causative organism. Increase in algal cell numbers are affected by season, temperature, amount of sunlight penetrating the water column, amount of available inorganic nutrients, competition from other algae and aquatic plants. High biomass blooms may cause significant ecological problems and harmful effects on the biota of the region like anoxia, community and food-web changes. But the toxin events may result from very low concentrations of the causative organisms and in the case of toxin events occurring with high biomass production, the toxicity level shoots to dangerous limits before the bloom is conspicuous. BGA have This ebook is exclusively for this university only. Cannot be resold/distributed.- eBook - PDF

- Glyn Barry Sykes, F. A. Skinner, Glyn Barry Sykes, F. A. Skinner(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Factors Affecting Algal Blooms J. A. STEEL Metropolitan Water Board, Water Examination Department, Roseberry Avenue, London E.C.I, England CONTENTS 1. Introduction 201 2. Requirements for growth 202 (a) Incident radiation 203 (b) Temperature 204 (c) Nutrients 206 (i) Essential elements 206 (ii) Nitrogen and phosphorus requirements 206 3. Algae in natural environments 208 (a) Bio tic interference 208 (b) Physical influences 210 4. Conclusions 212 5. Acknowledgments 212 6. References 213 1 . Introduction IN ALMOST ANY body of water at least one of the lower forms of plant or animal life is found; in most a great many such representatives will be algae. Whether or not such algae form a major part of the natural biocoenosis will depend to some extent on man's intervention in it, and whether or not their presence is desirable will depend on man's requirement of the particular ecosystem. These algae may be undesirable in that, even when relatively sparse, they so change the character of the medium that it becomes unacceptable. For instance, one may cite the colonial chrysophyte Synura uvella which is associated in water treatment systems with a very noticeable and persistent taste of cucumber. Some members of the Cyanophyta have been implicated in causing death or distress to cattle allowed to drink waters in which such algae were present. Microcystis aeruginosa, for example, has yielded extremely rapid and efficient toxins in laboratory extractions (Bishop et ai, 1959). The well publicized Red Tides· of a marine dinoflagellate are further instances of a primary producer creating considerable difficulties for other members of the ecosystem. Mostly, of course, the difficulties occasioned to man are far less dramatic but nonetheless can be disrupting. The presence of large blooms of algae is clearly only a disturbance to those who want the water in which the algae are thriving. 201 - eBook - PDF

- Wuncheng Wang, Joseph W. Gorsuch, Jane Hughes, Wuncheng (Woodrow) Wang, Joseph W. Gorsuch, Jane S. Hughes, Wuncheng (Woodrow) Wang, Joseph W. Gorsuch, Jane S. Hughes(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Blue-green Algal Blooms are comprised typ-ically of large filamentous species of Anabaena spp. and Microcystis spp., which are the most objectionable and undesirable since the toxins they produce adversely affect aquatic life and wildlife. Blue-green Algal Blooms occur worldwide, and their deleterious effects have been doc-umented since 1878 (Francis 1878). The neurotoxins and/or hepatotox-ins produced during bloom conditions have resulted in fatal poisonings of livestock, including horses, cattle, pigs, dogs, rabbits, and poultry. Neurotoxins are produced by strains of Anabaena flos-aquae and Apha-nizomenon flos-aquae . Hepatotoxins are produced by, among others, Microcystis aeuroginosa , Nodullaria spumigens , and various Oscillatoria species. In some cases, humans have been adversely affected after contact with fresh water containing blue-green Algal Blooms. The haz-ards of freshwater blue-green Algal Blooms are discussed in greater detail by Gorham and Carmichael (1990). Algal Blooms also can be caused by diatoms and dinoflagellates, such as species of Cyclotella, Synedra, Melosira, Fragilaria, and Stephan-odiscus . Marine dinoflagellates are best known for causing red tides Figure 3 Relative abundance of phytoplankton in a lake as related to fertility. (Adapted from Skulberg [1980].) © 1997 by CRC Press LLC 158 Plants for environmental studies which result in kills of fish, eichinoderms, and arthropods and cause various types of shellfish poisonings (Steidinger and Vargo 1990). Toxic dinoflagellate blooms can last for weeks or months, and the toxic spe-cies become almost monospecific at their peak. The cause of these blooms have been investigated, but a single cause has not been iden-tified. Algal Blooms die off eventually, decompose, and release nutrients. Bloom subsidence has been attributed to grazing, cell death, parasitism, advection, and shifts in the lifecycle. - Luis M. Botana, M. Carmen Louzao, Natalia Vilarino(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

Studies into the dynamics of cyanobacterial blooms predict that the expected increase in global temperature will result in increased surface water temperatures and thermal stratification, as well as changing meteorological patterns, possibly stimulating in- creased cyanobacterial growth rates [12–19]. It is likely that this will result in an in- creased frequency of cyanobacterial bloom events. Of particular concern to water utility managers are those cyanobacterial species that form blooms in freshwater reservoirs that are used for drinking, recreation and irrigation. 430 Dani J. Barrington, Xi Xiao, Liah X. Coggins and Anas Ghadouani Cyanobacterial blooms have several detrimental environmental effects. Blooms often proliferate in the surface layer of stratified reservoirs, shading organisms below, which can result in the death of pelagic and benthic organisms [20–23]. When blooms collapse, the release of organic cell matter to the water column increases the system’s oxygen demand. The concentration of dissolved oxygen is lowered due to its consumption in reactions to degrade organic and inorganic compounds; this re- sults in mass deaths of fish and other aquatic organisms [10, 24]. Such deaths are often observed by the general public and receive considerable media attention. Many species of cyanobacteria also produce toxins. Cyanobacterial toxins (cyanotox- ins) vary in their toxicity to humans and animals, and include hepatotoxins, dermatox- ins, cytotoxins, neurotoxins and lipopolysaccharides. Cyanotoxins can induce both acute and chronic effects and can pose a risk to both humans and ecological systems [25–32]. The most common routes of human contact with cyanotoxins are through the con- tamination of drinking water, the recreational use of lakes and rivers containing cyano- bacteria and via the ingestion of blue-green algal supplements [33–37].- eBook - ePub

Harmful Algal Blooms

A Compendium Desk Reference

- Sandra E. Shumway, JoAnn M. Burkholder, Steven L. Morton, Sandra E. Shumway, JoAnn M. Burkholder, Steven L. Morton(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

et al., 2008). Fucoidans, sulfated polysaccharides, are also produced by brown algae and have been reported to have antioxidant, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory activity (Vo and Kim, 2013). Macroalgae are often grown in order to harvest commercially important cell wall components, such as alginate, agar, and carrageenan (McHugh, 1991), and blooms could also be a source of these products.15.14 Forecast

Given the projected trajectories for increased cultural eutrophication and climate change in the United States and worldwide (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2015; World Resources Institute, n.d.), harmful macroAlgal Blooms ranging from freshwaters to brackish and coastal marine waters are predicted to increase in the coming decades. Considering benthic filamentous cyanobacteria, Quiblier et al. (2013) wrote, “As climatic conditions change and anthropogenic pressures on waterways increase, it seems likely that the prevalence of blooms of benthic cyanobacteria will increase.” Blooms of benthic filamentous cyanobacteria and filamentous green algae tend to be promoted by higher temperatures and nutrient pollution (Burkholder, 2009 and references therein; O'Neil et al., 2012). While more storms and rainfall would accelerate freshwater delivery of nutrients and flushing, longer drought periods would favor freshwater HAB by decreasing flushing and increase internal nutrient cycling. In coastal areas, predicted sea-level rise would increase the extent of continental shelf areas, providing shallow, stable coastal habitats that could favor macroalgal growth and/or expand suitable habitats inland (Harley et al., 2012; Teichberg et al., 2012 and references therein).Increasing ocean acidification may also promote the growth of macroalgae and lead to an increase in blooms. As seawater pH decreases, the percentage of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) that occurs as HCO3 − increases. The majority of marine macroalgae studied to date (> 85%) use a C3 photosynthetic process, including use of HCO3 − as a carbon source (Koch et al - eBook - PDF

Limnology

Some New Aspects of Inland Water Ecology

- Didem Gökçe(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- IntechOpen(Publisher)

Limnology and Oceanography. 1984; 29 :879-886 An Overview of Cyanobacteria Harmful Algal Bloom (CyanoHAB) Issues in Freshwater Ecosystems http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.84155 29 [52] Dokulil MT, Teubner K. Cyanobacterial dominance in lakes. Hydrobiologia. 2000; 438 :1-12. DOI: 10.1023/A:1004155810302 [53] Paerl HW, Gardner WS, Havens KE, Joyner AR, McCarthy MJ, Newell SE, et al. Mitigating cyanobacterial harmful Algal Blooms in aquatic ecosystems impacted by climate change and anthropogenic nutrients. Harmful Algae. 2016; 54 :213-222. DOI: 10.1016/j.hal.2015.09.009 [54] Fulton RS, Paerl HW. Effects of the blue-green alga Microcystis aeruginosa on zooplank -ton competitive relations. Oecologia. 1988; 76 :383-389. DOI: 10.1007/BF00377033 [55] Lampert W. Laboratory studies on zooplankton-cyanobacteria interactions. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 1987; 21 :483-490. DOI: 10.1080/ 00288330.1987.9516244 [56] Wilson AE, Sarnelle O, Tillmanns AR. Effects of cyanobacterial toxicity and morphol -ogy on the population growth of freshwater zooplankton: Meta-analyses of labora -tory experiments. Limnology and Oceanography. 2006; 51 :1915-1924. DOI: 10.4319/ lo.2006.51.4.1915 [57] Figueiredo MAT, Nowak RD, Wright SJ. Gradient projection for sparse reconstruction: Application to compressed sensing and other inverse problems. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing. 2007; 1 :586-597. DOI: 10.1109/JSTSP.2007.910281 [58] Antunes JT, Leão PN, Vasconcelos VM. Influence of biotic and abiotic factors on the alle -lopathic activity of the cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii strain LEGE 99043. Microbial Ecology. 2012; 64 :584-592. DOI: 10.1007/s00248-012-0061-7 [59] Azevêdo DJS, Barbosa JEL, Porto DE, Gomes WIA, Molozzi J. Biotic or abiotic factors: Which has greater influence in determining the structure of rotifers in semi-arid reser -voirs? Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia. - eBook - PDF

Oceanography and Marine Biology

An Annual Review, Volume 50

- R. N. Gibson, R. J. A. Atkinson, J. D. M. Gordon, R. N. Hughes(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Scottish Executive Environment Group Paper. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2006/02/03095327/ Accessed 5 September 2011. Smayda, T.J. 2008. Complexity in the eutrophication-harmful algal bloom relationship, with comment on the importance of grazing. Harmful Algae 8 , 140–151. Smayda, T.J. & Reynolds, C.S. 2001. Community assembly in marine phytoplankton: application of recent models to harmful dinoflagellate blooms. Journal of Plankton Research 23 , 447–461. Smayda, T.J. & White, A.W. 1990. Has there been a global expansion of Algal Blooms? If so, is there a con-nection with human activities? In Toxic Marine Phytoplankton. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Toxic Marine Phytoplankton, 26–30 June 1989, Lund, Sweden , E. Granéli et al. (eds). New York: Elsevier Science, 516–517. Smayda, T. & Wyatt, T. 1995. Round table-Global spreading hypothesis. In Harmful Marine Algal Blooms Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Toxic Marine Phytoplankton October 1993, Nantes, France , P. Lassus et al. (eds). Paris: Lavoisier, 81–86. Smith, R.L. 1968. Upwelling. Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review 6 , 11–46. Smith, S.V., Boudreau, P.R. & Ruardij, P. 1997. NP budget for the southern North Sea. Stockholm, LOICZ— Biogeochemical Modelling Node. Online. nest.su.se/mnode/Europe/NorthSea/NORTHSEA.HTM/ Accessed 13 June 2011. Sournia, A. 1995. Red tide and toxic marine phytoplankton of the world ocean: an inquiry into biodiversity. In Harmful Marine Algal Blooms Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Toxic Marine Phytoplankton October 1993, Nantes, France , P. Lassus et al. (eds). Paris: Lavoisier, 103–112. Stigebrandt, A. 2011. Carrying capacity: general principles of model construction. Aquaculture Research 42 , 41–50. Stigebrandt, A., Aure, J., Ervil, A. & Hansen P.K. 2004. Regulating the local environmental impact of intensive marine fish farming III.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.