Biological Sciences

Baltimore Classification

The Baltimore Classification is a system used to categorize viruses based on their genome type and replication strategy. It was developed by David Baltimore in 1971 and classifies viruses into seven groups (I-VII) based on the type of nucleic acid they contain and how that nucleic acid is replicated. This classification system provides a framework for understanding the diversity of viruses.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Baltimore Classification"

- No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- College Publishing House(Publisher)

A unified taxonomy (a universal system for classifying viruses) has been established. The 7th lCTV Report formalised for the first time the concept of the virus species as the lowest taxon (group) in a branching hierarchy of viral taxa. However, at present only a small part of the total diversity of viruses has been studied, with analyses of samples from humans finding that about 20% of the virus sequences recovered have not been seen before, and samples from the environment, such as from seawater and ocean sediments, finding that the large majority of sequences are completely novel. The general taxonomic structure is as follows: Order (-virales) Family (-viridae) Subfamily (-virinae) Genus ( -virus ) Species ( -virus ) In the current (2008) ICTV taxonomy, five orders have been established, the Caudo-virales, Herpesvirales, Mononegavirales, Nidovirales, and Picornavirales. The committee does not formally distinguish between subspecies, strains, and isolates. In total there are 5 orders, 82 families, 11 subfamilies, 307 genera, 2,083 species and about 3,000 types yet unclassified. ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Baltimore Classification The Baltimore Classification of viruses is based on the method of viral mRNA synthesis The Nobel Prize-winning biologist David Baltimore devised the Baltimore Classification system. The ICTV classification system is used in conjunction with the Baltimore Classification system in modern virus classification. The Baltimore Classification of viruses is based on the mechanism of mRNA production. Viruses must generate mRNAs from their genomes to produce proteins and replicate themselves, but different mechanisms are used to achieve this in each virus family. Viral genomes may be single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds), RNA or DNA, and may or may not use reverse transcriptase (RT). Additionally, ssRNA viruses may be either sense (+) or antis ense (−). - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Orange Apple(Publisher)

A unified taxonomy (a universal system for classifying viruses) has been established. The 7th lCTV Report formalised for the first time the concept of the virus species as the lowest taxon (group) in a branching hierarchy of viral taxa. However, at present only a small part of the total diversity of viruses has been studied, with analyses of samples from humans finding that about 20% of the virus sequences recovered have not been seen before, and samples from the environment, such as from seawater and ocean sediments, finding that the large majority of sequences are completely novel. The general taxonomic structure is as follows: Order (-virales) Family (-viridae) Subfamily (-virinae) Genus ( -virus ) Species ( -virus ) In the current (2008) ICTV taxonomy, five orders have been established, the Caudovirales, Herpesvirales, Mononegavirales, Nidovirales, and Picornavirales. The committee does not formally distinguish between subspecies, strains, and isolates. In total there are 5 orders, 82 families, 11 subfamilies, 307 genera, 2,083 species and about 3,000 types yet unclassified. ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Baltimore Classification The Baltimore Classification of viruses is based on the method of viral mRNA synthesis. The Nobel Prize-winning biologist David Baltimore devised the Baltimore Classification system. The ICTV classification system is used in conjunction with the Baltimore Classification system in modern virus classification. The Baltimore Classification of viruses is based on the mechanism of mRNA production. Viruses must generate mRNAs from their genomes to produce proteins and replicate themselves, but different mechanisms are used to achieve this in each virus family. Viral genomes may be single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds), RNA or DNA, and may or may not use reverse transcriptase (RT). Additionally, ssRNA viruses may be either sense (+) or antisense (−). - eBook - PDF

- Smith, P(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Agri Horti Press(Publisher)

Another factor causing difficulties in virus classification is their pseudo-living nature, many scientists are debating whether viruses should be considered alive because they are missing several criteria considered important for living creatures. This makes viruses very difficult to place in the current classification system for plants and animals. Virus classification is currently based on five phenotypic characteristics; morphology, or structure, of the virus; type of nucleic acid, or the genetic material, of the virus; mode of replication; hosts; and the type of disease they cause. There are two classification systems in use today, the Baltimore system and the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses classification guidelines. The Baltimore Classification system was developed by Nobel Prize winning biologist, David Baltimore. This system separates viruses into seven groups, designated by Roman numerals, depending on their type of genetic material, the number of strands of genetic material and their method of This ebook is exclusively for this university only. Cannot be resold/distributed. General Microbiology 78 replication. There are other classification systems that are based on the morphology of the virus or the disease caused. These systems are inadequate due to the fact that some diseases are caused by different viruses, the cold or flu are the most common example of this and some viruses look very similar to one another. Another factor is viral structures are difficult to determine under a microscope thanks to their small size. By classifying viruses based on their genetic material, some indication of how to proceed with research is provided because viruses in a category behave in a similar manner. - Diwakar, R K(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Daya Publishing House(Publisher)

In the ICTV have six sub-committees, 45 study groups and more than 400 virologists. ICTV develop universal scheme, Virion characteristics are considered and weight by these criteria to division into the families, in some cases sub-families and genera. Now three orders (Mononegavirales, Nidovirales, and Caudovirales) have been approved. More than 1550 viruses species belonging to 3 orders, 56 families, 9 sub-families and 233 genera are recognised Classification Viruses are classed into 7 types of genes and each of which has its own families of viruses, which in turn have differing replication strategies themselves. David Baltimore, a Nobel Prize-winning biologist, devised a system called the Baltimore Classification System to classify different viruses based on their unique replication strategy. There are seven different replication strategies based on this system (Baltimore Class I, II, III, IV, V, VI, and VII). Class 1: Double-Stranded DNA Viruses This type of virus usually must enter the host nucleus before it is able to replicate. Some of these viruses require host cell polymerases to replicate their genome, while others, such as adenoviruses or herpes viruses, encode their own replication factors. However, in either cases, replication of the viral genome is highly dependent on a cellular state permissive to DNA replication and, thus, on the cell cycle. The virus may induce the cell to forcefully undergo cell division, which may lead to transformation of the cell and, ultimately, cancer. An example of a family within this classification is the Adenoviridae. There is only one well-studied example in which a class 1 family of This ebook is exclusively for this university only. Cannot be resold/distributed. viruses does not replicate within the nucleus. This is the Poxvirus family, which comprises highly pathogenic viruses that infect vertebrates.- eBook - PDF

- Nigel J. Dimmock, Andrew J. Easton, Keith N. Leppard(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

This system provides an opportunity to make inferences and predictions about the fundamental nature of all viruses within each defined group. The original Baltimore Classification scheme was based on the fundamental importance of messenger RNA (mRNA) in the replication cycle of viruses. Viruses do not contain the molecules necessary to translate mRNA and rely on the host cell to provide these. They must therefore synthesize mRNAs which are recognized by the host cell ribosomes. In the Baltimore scheme, viruses are grouped according to the mechanism of mRNA synthesis Fig. 3.1 The Baltimore Classification scheme (see text for details). mRNA is designated as positive sense. Translation of protein from mRNA and positive sense RNA virus genomes is indicated with dashed red arrows. The path of production of mRNA from double-stranded templates is shown with solid black arrows. Blue arrows show the steps in the replication of the various types of genome with double-headed arrows indicating production of a double-stranded intermediate from which single stranded genomes are produced. which they employ (Fig. 3.1). By convention, all mRNA is designated as positive (or ‘plus’) sense RNA. Strands of viral DNA and RNA which are complementary to the mRNA are designated as negative (or ‘minus’) sense and those that have the same sequence are termed ‘positive’ sense. Using this terminology, coupled with some additional information about the replication process, a modified classification scheme based on the original proposed by Baltimore defines seven groups of viruses, with each commonly being referred to by the nature of the virus genomes it includes: 34 Part I The nature of viruses Class 1 contains all viruses that have double- stranded (ds) DNA genomes. In this class, the designation of positive and negative sense is not meaningful since mRNAs may come from either strand. Transcription can occur using a process similar to that found in the host cells. - eBook - PDF

- Mary Ann Clark, Jung Choi, Matthew Douglas(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Openstax(Publisher)

However, these earlier classification methods grouped viruses differently, because they were based on different sets of characters of the virus. The most commonly used classification method today is called the Baltimore Classification scheme, and is based on how messenger RNA (mRNA) is generated in each particular type of virus. Past Systems of Classification Viruses contain only a few elements by which they can be classified: the viral genome, the type of capsid, and the envelope structure for the enveloped viruses. All of these elements have been used in the past for viral classification (Table 21.1 and Figure 21.6). Viral genomes may vary in the type of genetic material (DNA or RNA) and its organization (single- or double-stranded, linear or circular, and segmented or non-segmented). In some viruses, additional proteins needed for replication are associated directly with the genome or contained within the viral capsid. Virus Classification by Genome Structure Genome Structure Examples RNA DNA Rabies virus, retroviruses Herpesviruses, smallpox virus Single-stranded Double-stranded Rabies virus, retroviruses Herpesviruses, smallpox virus Linear Circular Rabies virus, retroviruses, herpesviruses, smallpox virus Papillomaviruses, many bacteriophages Non-segmented: genome consists of a single segment of genetic material Segmented: genome is divided into multiple segments Parainfluenza viruses Influenza viruses Table 21.1 564 Chapter 21 | Viruses This OpenStax book is available for free at http://cnx.org/content/col24361/1.8 Figure 21.6 Viruses can be classified according to their core genetic material and capsid design. (a) Rabies virus has a single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) core and an enveloped helical capsid, whereas (b) variola virus, the causative agent of smallpox, has a double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) core and a complex capsid. Rabies transmission occurs when saliva from an infected mammal enters a wound. - eBook - ePub

- Avindra Nath, Joseph R. Berger, Avindra Nath, Joseph R. Berger(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

http://viralzone.expasy.org/all_by_species/254.html .)Although the Baltimore Classification scheme is based on the transcription strategies of viruses, the various classes usually can be distinguished by the manner in which the viral genomes are replicated. Class I viruses use their dsDNA genomes as a template to synthesize more dsDNA during genome replication. As in transcription, this replication is usually carried out by host enzymes. Class VII Hepadnaviridae are an exception to this generalization; replication takes place through an RNA intermediate that is longer than the genome. Class II viruses go through a replicative intermediate to copy their genomes. For example, (+)ssDNA viruses must make a (−)ssDNA copy to act as a template for more (+)ssDNA. In the case of class III viruses, the mRNA that was used for protein synthesis is copied by viral enzymes into a (−) sense RNA that remains associated with the mRNA template to form the progeny dsRNA. Class IV viruses have (+)ssRNA genomes. A (−)ssRNA intermediate is produced, which then serves as the template for more (+)ssRNA. Class V viruses use the same replication strategy as class IV viruses, except that they start with a (−)ssRNA genome and use a (+)ssRNA strand as an intermediate. In class VI, (+)ssRNA genomes are replicated by a unique mechanism. The (+)ssRNA is used as a template to synthesize (−)ssDNA, which in turn serves as a template for the synthesis of a (+)ssDNA strand. The resulting dsDNA molecule is transcribed into mRNA or used to synthesize progeny (+)ssRNA genomes.1.2.2 Integration of classification schemes

1.2.2.1 DNA VIRUSES

Any number of classification schemes may be employed by researchers and healthcare professionals, but for our purpose, it is simpler to separate viruses according to their genomes (whether the genome is DNA or RNA, ss or ds) and virion morphology (whether the virus has an envelope and the overall shape of the particle). DNA viruses follow a more conventional replication strategy, although their genome shapes, sizes, and organizations, as well as the virion structures, are quite varied. Double-stranded DNA viruses that belong to class I of the Baltimore Classification scheme can be further divided based upon presence or absence of an envelope. Relevant viruses that lack an envelope include JC virus and adenovirus, both of which have icosahedral capsids. Examples of enveloped dsDNA viruses are members of the family Herpesviridae - eBook - PDF

- Frank J. Fenner, B. R. McAuslan, C. A. Mims(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

12 1. Nature and Classification of Animal Viruses of diseases caused by them, which tended to classify the host responses rather than the viruses. Bawden (1941) made the pioneering suggestion that viral no-menclature and classification should be based upon properties of the virus particle. In the early 1950's Bawden's approach was exploited by animal virologists (Andrewes, 1952), and viruses were allocated to groups which were usually given latinized names constructed from a chosen prefix plus the word virus. Thus, myxovirus (Andrewes et ah, 1955), poxvirus (Fenner and Burnet, 1957), herpesvirus (Andrewes, 1954), reovirus (Sabin, 1959), papovavirus (Melnick, 1962), picornavirus (International Enterovirus Study Group, 1963), and adeno-virus (Pereira et ah, 1963) groups were described. In the meantime, a classifica-tion using quite different criteria had been established by epidemiologists. Since they were so concerned with the transmission of infection, epidemiologists have used a classification based on the mode of transmission of disease; they have grouped viruses together as respiratory viruses, enteric viruses, or ar-thropod-borne (arbo-) viruses. The last term, in particular, has been widely used, but it is generally agreed that this epidemiological classification, although useful is in no sense taxonomic. Concurrently with these suggestions relating to the viruses of vertebrates, Lwoff (1957) insisted upon the similarities between viruses, whatever their natural host, and the differences between viruses and all other biological entities. He was instrumental in arranging for the establishment of an international com-mittee (Anon., 1965; Lwoff and Tournier, 1966) to discuss nomenclature. Its major proposal was to select type species upon which names for groups would be based. - eBook - ePub

- Anil K. Sharma, Girish Kumar Gupta, Mukesh Yadav, Anil K. Sharma, Girish Kumar Gupta, Mukesh Yadav(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

Viruses are known to be obligate intracellular parasites. They are acellular infectious agents that cannot multiply without a living host. When found outside of host cells, they are metabolically inert particles. These particles have a protein coat surrounding them called capsid which may or may not be enclosed in a membrane. This protein coat (capsid) envelopes either deoxyribonucleic acids (DNA) or ribose nucleic acids (RNA), which codes for the virus proteins. When it meets a host cell, a virus can inject its genetic material into the host cell, hijacking the host’s fundamental functions for its own replication and multiplication. Unlike most living things, viruses can only divide in the infected host cell. Viruses spread in many ways and have distinct mechanism of infection, pathogenesis and symptoms. Most of the time, they are usually eliminated by the host immune system, and diseases are prominent in immunocompromised host. This chapter discusses the mode of infection, life cycle, pathogenesis, diagnosis, control and prevention of various viral infections.3.2 Viral classification, structure and multiplication

The classification of viruses involves naming and putting them into different taxonomic categories. However, viruses do not have ribosomes (therefore, ribosomal RNA is also absent, which is widely used in classification of other microorganisms); hence, they cannot be classified as per the three-domain classification scheme. There are two main classification systems adopted for viruses: The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) system and Baltimore Classification system.The International Union of Microbiological Societies selected ICTV which started in the 1970s for the nomenclature and classification of the viruses. Since then, they are developing, redefining, naming and maintaining universal virus taxonomy. The ICTV divided viruses into order (-virales), family (-viridae), subfamily (-virinae), genus (-virus) and species. The first report was published in 1971 with 43 virus groups. Recently, the Ninth Report was published with 1,327 pages and described 87 viral family totaling 2,284 species [1 ]. The major orders that span viruses with varying host ranges are the Herpesvirales, Caudovirales, Nidovirales, Ligamenvirales, Picornavirales, Mononegavirales and Tymovirales. They also created nine unassigned genera including Aumaivirus, Papanivirus, Sinaivirus, Virtovirus, Anphevirus, Arlivirus, Chengtivirus, Crustavirus and Wastrivirus in the order Mononegavirales, and eight new families including Botybirnaviridae, Genomoviridae, Lavidaviridae, Mymonaviridae, Pleolipoviridae, Pneumoviridae, Sarthroviridae and Sunviridae [1 - eBook - PDF

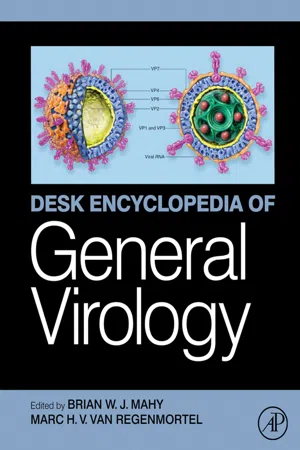

- Marc H.V. van Regenmortel, Brian W.J. Mahy(Authors)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

It is also clear that hierarchical classification above the family level will encounter conflicts between phenotypic and genotypic criteria and that virologists may have to reconsider the entire classification process in order to progress at this level. Virus Taxa Descriptions Virus classification continues to evolve with the technol-ogies available for describing viruses. The first wave of descriptions, those before 1940, took into account mostly the visual symptoms of viral diseases along with modes of viral transmission. A second wave, between 1940 and 1970, brought together an enormous amount of informa-tion from studies of virion morphology (electron micros-copy, structural data), biology (serology and virus properties), and physicochemical properties of viruses (nature and size of the genome, number and size of viral proteins). The impact of descriptions on virus classification has been particularly influenced by elec-tron microscopy and the negative-staining technique for virions in the 1960s and 1970s. With this technique, viruses could be identified from poorly purified pre-parations of all tissue types and information about size, shape, structure, and symmetry could be quickly pro-vided. As a result, virology progressed simultaneously for all viruses infecting animals, insects, plants, and bacte-ria. Since 1970, the virus descriptors list has included genome and replication information (sequence of genes, sequence of proteins), as well as molecular relationships with virus hosts. The most recent wave of information used to classify viruses is virus genome sequences. Genome sequence comparisons are becoming more and more prevalent in virus taxonomy as exemplified by the presence of a sig-nificant number of phylogenetic trees in the Eighth ICTV Report . Some scientists promote the concept of quantita-tive taxonomy, aimed at demonstrating that virus genome sequences contain all the coding information required for all the biological properties of the viruses. - eBook - PDF

International Congress for Microbiology

Moscow, 1966

- Sam Stuart(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Pergamon(Publisher)

But till now nobody could succeed in dividing them. Perhaps this is the reason why our symposium on classification of viruses has taken the suggestions made by the PCNV as a basis for discussion. Sceptics consider the viral classification to be impossible on the present level of science because our knowledge is too limited. It seems though that the obstacle lies not in the fact that our knowledge is too limited but in our limited knowledge on the following subject: which characters are really essential. Early attempts to build a classification of viruses (Holmes, 1958; Zhdanov a. Corenblit, 1950; Ryzkov, 1950; Zhdanov, 1953) failed because the characters of the viral particle weren't chosen as the leading principle (only dimensions were taken into consideration). The classifications were based on such features as susceptibility of certain hosts, mode of dissemination, clinical signs. These classifications are of interest not only as early attempts to systematize our knowledge on viruses but also as valuable catalogues containing a description of viruses known at that time. The data on viral morphology were then very limited. Electron microscopy gave only a picture of external shape of viral particles. This gap in our knowledge was — 411 — 412 considered to be one of the main obstacles on the way to a rational classification of viruses. When the progress in this field of virology had started it was suggested to use for classification the type of symmetry, the number of caspomeres and the presence of envelope (Home, Wildy, 1961; Almeida, 1963). Wildy (1962) brilliantly developed this idea in a special work on viral classification with the use of the type of symmetry and the structure of the virus particle as criteria.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.