Biological Sciences

Classification Systems

Classification systems in biological sciences are frameworks used to categorize and organize living organisms based on their shared characteristics. These systems help scientists understand the diversity of life and its evolutionary relationships. They typically involve hierarchical levels, such as domain, kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species, and are constantly evolving as new discoveries are made.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Classification Systems"

- No longer available |Learn more

- Azhar ul Haque Sario(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- tredition(Publisher)

ClassificationConcept and use of a classification systemClassifying organisms into groups based on shared characteristics is a fundamental aspect of biological science, often referred to as taxonomy. This classification system is not merely a tool for organizing and naming species, but it also provides deep insights into the evolutionary relationships and histories of different organisms.1. The Essence of Biological ClassificationImagine entering a library where books are scattered without any order. Finding a specific book in such chaos would be a daunting task. Biological classification works similarly to a library system. It's a method of categorizing living beings in a way that accentuates their common features and relationships, making the study of such a diverse range of life forms manageable and systematic.2. Historical PerspectivesThe journey of classification began centuries ago. Aristotle, the ancient Greek philosopher, is one of the earliest known figures to attempt categorizing living beings. He distinguished animals based on simple characteristics like their habitat and body parts. However, his approach had limitations, lacking a scientific foundation for these classifications.The real transformation in biological classification occurred with Carl Linnaeus, a Swedish botanist, zoologist, and physician in the 18th century. He introduced a hierarchical system, known as the Linnaean system, categorizing species based on shared physical characteristics.3. Modern Classification SystemsIn modern biology, the classification system has evolved considerably. It's not just about physical similarities anymore. The advent of molecular biology and genetic sequencing has revolutionized our understanding. Scientists now consider DNA sequences, biochemical pathways, and genetic relationships when classifying organisms, leading to more accurate and evolutionary meaningful groupings.4. Hierarchy in Classification - eBook - PDF

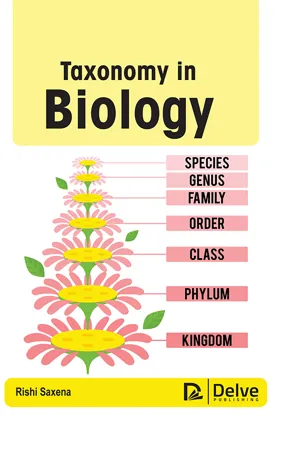

- Rishi Saxena(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Delve Publishing(Publisher)

Biologists, on the other hand, have endeavored to observe all living species with similar thoroughness, resulting in a systematic taxonomy. A formal categorization serves as the foundation for a general standard and widely known nomenclature, which simplifies cross-referencing and information retrieval. The terms “taxonomy” and “Systematics” are used differently in biological categorization. According to American evolutionist Ernst Mayer, “taxonomy is the theory and practice of classifying organisms,” while “Systematics is the science of organism diversity”; the latter, in this context, does have significant interrelationships with evolution, ecology , genetics, behavior, and comparative physiology that taxonomy doesn’t really. The process of taxonomy involves two distinct steps: (i) Accurate identification and description of species and its relationships; and (ii) Use of appropriate names for organisms and groupings that contain them. The former is known as classification, which encompasses the analysis of traits as well as the classification of individuals, whereas the latter is known as nomenclature. Taxonomy in Biology 4 1.2. HISTORY OF TAXONOMY People who live in close proximity to nature typically have a strong understanding of the local fauna and flora, as well as the ability to recognize several of the larger groups of living creatures (e.g., fishes, birds, and mammals). Its expertise, on the other hand, is situational, and such people very rarely generalize. Nevertheless, the ancient Chinese and Egyptians made some of the first ventures into formal, though restricted, classification. In China, a collection of 365 medicinal plant species served as the foundation for later hydrological investigations. Although the inventory is assigned to the mythological Chinese emperor Shennong, who lived around 2700 years ago, it was most likely composed around the turn of the century. - eBook - PDF

Chemistry in Botanical Classification: Medicine and Natural Sciences

Medicine and Natural Sciences

- Gerd Bendz(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

For example, Birch [1] in a paper delivered at the IUPAC symposium in Stras-bourg in July 1972 on Chemistry in evolution and systematics writes: Attempts have been made to assist that essentially artificial classifi-cation, taxonomy, by considering the structures of plant constituents as markers on a level with morphological characteristics. Ignoring the fact that I do not understand what this com-ment means as written, two of the key words used are classification and taxonomy, and other terms to be considered include systematics, rela-tionships, phylogeny, phenetic, phyletic/phylo-genetic, evolutionary (as applied to systems of or approaches to classification and relation-ships). I assume that the title of this symposium is not to be understood literally, as classification is but one aspect of the general field of sys-tematics and consequently of biochemical sys-tematics (if such a term is admitted, see below for discussion). Definitions (a) Systematics. In the broadest sense, system-atics is concerned with the scientific study of the diversity and differentiation of organisms and the relationships (of any kind) that exist between them [2, 3]. Without further qualifica-tion (other than botanical/zoological/fungal/ microbial, etc.) it embraces phylogenetic, evo-lutionary, phenetic, morphological, traditional, classical, etc. approaches. It can cover such Nobel 25 (1973) Chemistry in botanical classification 42 V. H. Heywood studies at all levels in the hierarchy, ranging from the individual and population level to the family, order, class and even higher levels. At the lower levels of the hierarchy, it includes what is often called biosystematics and indeed Solbrig's recent text book entitled Plant bio-systematics [4] is, in effect, a contribution to plant systematics. - eBook - PDF

- James Maclaurin, Kim Sterelny(Authors)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- University of Chicago Press(Publisher)

In this section, we discuss the general problem of classification sys-tems in biology, taking as our stalking horse the most familiar example: the Linnaean classification system, the system that begins by classify-ing species into genera, that is, into sets of closely related and similar species. This system is not just the best-known classification system in biology; it is also of fundamental importance given the common prac-tice within conservation biology of using species and species richness as proxy for biodiversity in general. 3 Natural Classification To understand a system we need to identify the units out of which the system is built, and whose actions and interactions drive the system. And we have to identify the crucial differences between those units. This is true of biological systems, but not only biological systems. Thus in trying to understand human cultures we need to identify the agents whose interactions constitute those cultures. Are all social agents in-dividual human beings? Or do they include certain collective agents 10 c h a p t e r o n e as well (tribes, firms, unions, and other institutions)? Moreover, we have to identify the crucial similarities and differences between human agents. Understood this way, constructing a classification system is far from trivial. Solving problems of this form was the key to the revolution in understanding chemical systems that began in the late eighteenth century. Indeed, solving the units-and-differences problem is central to any attempt to understand a domain. Moreover, a good taxonomy is an enormously important tool, because a good system of classifica-tion links diagnostic criteria for identification with similarity in causal profile. Consider, for example, the folk psychological category of anger. An-ger is diagnosable; it is not diffi cult to recognize the truly angry. And anger is causally significant; the angry are disposed to act in rather simi-lar ways. - eBook - PDF

Collaborative Teaching in the Middle Grades

Inquiry Science

- Helaine Becker(Author)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Libraries Unlimited(Publisher)

Therefore, we must still rely on morphological characteristics—appearance—to identify species’ differences. In conclusion, taxonomy is useful as an aid for understanding the structures and relationships of liv- ing things. But ultimately, it is only a human construct, one that reflects the biases and ideologies of its makers. Glossary • Analogous —similar or comparable in certain aspects • Cladogram—a branching diagram to illustrate speciation and the relationships between species • Class—a major category in the classification of living things, ranking above an order and be- low a division or phylum • Genus—a major category in the classification of living things, ranking above a species and below a family • Homologous—corresponding in basic type of structure and deriving from a common primi- tive organ • Kingdom—a major category in the classification of living things, ranking above a division or phylum • Order—a major category in the classification of living things, ranking above a family and be- low a class • Phylogeny—the evolutionary lines of descent of any plant or animal species • Species—a naturally existing population of similar organisms that interbreed only among themselves • Taxonomy—the system of classification whereby plants and animals are arranged into natu- ral, related groups based on common factors Glossary 7 Information for the Student: Classification of Organisms In this unit, you will explore how organisms have been classed in different ways as a means to understand them. You will also meet a giant in the field of science, Linnaeus, who created the basic classification system that scientists use today. To succeed in this activity, you will need to do research using a variety of media and infor- mation sources. You will then need to apply what you have learned to identify and classify a mystery organism. - eBook - PDF

- Kostas Kampourakis, Tobias Uller(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

what is the basis of biological classification? 217 be counted as a new species or as a variety of a species that is already known, and so on. But such practical problems have a specific theoret- ical context and history. They are connected to a persistent lack of clarity regarding what aspects of nature biological classifications are supposed to represent, as well as to debates regarding the meaning of many core terms that feature in biological classifications (such as “species” and “gene”), and to how these concepts have changed as biology developed as a science. Practical problems in classifying organisms partly arise because it is unclear which criteria we should use to group individual organisms into species and to delimit species from one another. The same holds for questions about genetic diversity, where biologists disagree on what segments of DNA count as genes, and how these are best grouped into gene families and so on. History and philosophy of science are important here, because they illuminate the historical background and the theor- etical context of many problems that working scientists are confronted with in their daily practice. This is one reason why history and philoso- phy of science are important for working biologists, for biology educa- tors, and for anyone who wants to understand how biology as a science works and what the nature is of the knowledge that it produces about the living world. In what follows, I illustrate this by examining two cases of biological classification: the classification of organisms into species and other taxa, and the classification of genes into kinds. I focus on what a natural system of classification actually is; the assumption that there is a nat- ural order in the living world; the conceptual difficulties surrounding the classificatory concepts of “species” and “gene”; and the theory- dependence of classifications. - eBook - PDF

- Jack Meadows(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter Saur(Publisher)

CHAPTER THREE Classification Classifying things into groups does not sound very exciting. Indeed, many students of zoology and botany regard classification as one of the most boring parts of their course. Yet classification forms the basis for much of our understanding of the world around us. We use it all the time. Go into a shop, buy something, and put the change away. The odds are that you will put the notes in one place and the coins in another. You have classified the change in terms of its physical characteristics. At a more basic level, young children must learn how to classify in order to grasp the world around them. Their first step is to attach names to the things they frequently encounter. Thus, this household pet is called a dog, that one is a cat. The second step, which proves much more difficult, is to understand that the two animals next door must also be recognized as a cat and dog. This is the move to classification - the activity, as my dictionary reasonably says, of arranging things into categories. It is not until children are well-embarked on their school careers that they realize such names are arbitrary labels. It would be perfectly acceptable to call a 'dog' a 'cat' and vice versa, so long as everyone agreed to use the words in that way. Classification is an activity that relates immediately to information. The study of classification is often called 'systematics'. Our earlier definition of information was 'systematically organized data'. The word 'system', which appeared undefined in the last chapter, lies at the core of both of these. When it comes to explaining what a 'system' is, my dictionary really goes to town. It gives twelve definitions. Most of these 30 Classification can be interpreted as meaning 'a set of things that work together in a continuing way'. For example, human beings are systems because the various parts of their bodies work together (generally) to ensure that we function with reasonable efficiency. - eBook - PDF

Cladistics: Perspectives on the Reconstruction of Evolutionary History

Papers Presented at a Workshop on the Theory and Application of Cladistic Methodology, March · 22–28, 1981, University of California, Berkeley

- Thomas Duncan, Tod F. Stuessy, Thomas Duncan, Tod F. Stuessy(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Columbia University Press(Publisher)

13 Considerations in Formalizing a Classification RAYMOND B . PHILLIPS Classification, followed by the application of names, is an essential part of human thought and communication. It is an activity that summarizes ob-served patterns. The best classifications are those that are based on the largest possible pool of information evaluated by a means appropriate to the use to be made of the classification, thus conveying the largest amount of in-formation. In botanical classification, the work of such pre-Darwinians as Jussieu (1789) and Candolle (1813) resulted in classifications commonly referred to as natural in many introductory plant taxonomy textbooks (e.g., Ben-son 1979; Jones and Luchsinger 1979). These systems, particularly at the generic and familial ranks, were based on a large assortment of characters observed in the plants, and groups were defined by the observed similari-ties among them. Most of the changes found in classifications since then at these ranks have been primarily the result of the acquisition of a large amount of new data (see Engler and Prantl 1898; Takhtajan 1969; Cronquist 1981). The impact of evolutionary theory on biological classification has been pri-marily as a means of explaining the patterns of similarity that are observed and incorporated in the classifications, rather than directly affecting the classifications. Evolutionary theory has had so little impact because the same operational approach has been used throughout most of the recent history of classification. Namely, similar organisms are grouped together, the gaps between groups of organisms, as evidenced by the distribution of character states, providing the basis for the classification. The recognition of such groupings and gaps does not require evolutionary theory, although they may be interpreted in an evolutionary context. One of the strongest and most explicit statements in support of this approach is that of McNeill (1979): - eBook - PDF

Vistas in Botany

Recent Researches in Plant Taxonomy

- W. B. Turrill(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Pergamon(Publisher)

This factor can perhaps be best described as the act, conscious or unconscious, of grouping objects into a class because of certain attri- butes or relationships that they have in common.* If we accept this definition of classification, it is clear that a study of classification may lead us into many and diverse branches of human knowledge. The giving of names such as house, table, dog, etc., plunges us into the realms of philosophy and metaphysics, touching on such questions, for example, as the existence or non-existence of universals; while, at the other extreme, the devising of formal systems of classifi- cation brings in ist train practical considerations of the rules of nomen- clature, and, in the case, for example, of library classification, of mechan- ical methods of indexing, cataloguing, and cross-referencing. Despite the close relationship between the different activities gathered together under the term classification, the great majority of biologists concerned with the classification of living things have held aloof from the other fields in which the theory and practice of classification have * "Relationships" covers such cases as all objects occurring at a certain time or place; hereafter "attributes" is to be taken as including relationships. The phrase "in common" does not imply that all the objects necessarily possess the attributes con- cerned, but is intended to indicate that all possess at least a high proportion of them. 1 2 J. S. L. GILMOUR AND S. M. WALTERS been studied, especially the philosophic field, and have paid little atten- tion to the discussions in these fields of problems very similar to their own—and this despite the fact that most workers in these fields have used biological classification to illustrate their discussions. - eBook - PDF

Systems Science

Methodological Approaches

- Yi Lin, Xiaojun Duan, Chengli Zhao, Li Da Xu(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Each object studied in any disci-pline appears as a system. That is, different scientific disciplines focus on the investigation of sys-tems of particular characteristics. As a matter of fact, modern science is compartmented according to the differences in the object systems. For instance, studies of natural systems are categorized into natural science; investigations of social systems are considered parts of social science. Natural sci-ence is further compartmented based on the attributes of the objects studied, leading to the creation of finer disciplines. Such method of classification emphasizes the basic qualitative characteristics of parts without considering the systemicality and wholeness. Thus, it is a nonsystems scientific classification. 2.4.2 S YSTEMS S CIENTIFIC C LASSIFICATION OF S YSTEMS When systems are classified and studied according to their characteristics of wholeness without considering any particular properties of parts, what results are the disciplinary branches and theo-retical structure of systems science. In the following, let us briefly introduce several methods of systems classification. General systems and particular systems: This is the classification method Bertalanffy (1968) established. He believes that there are models, principles, and laws that are applicable to general systems; these models, principles, and laws have nothing to with the classification of specific sys-tems, properties of parts, and characteristics of the “forces” or relationships between the key fac-tors. Here the phrase “specific systems” stands for different classes of general systems. It does not involve the basic properties of systems’ parts.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.