Biological Sciences

Taxonomy

Taxonomy is the science of classifying and naming organisms based on their characteristics and evolutionary relationships. It involves organizing species into hierarchical categories, such as kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. Taxonomy helps scientists understand the diversity of life and how different organisms are related to each other.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Taxonomy"

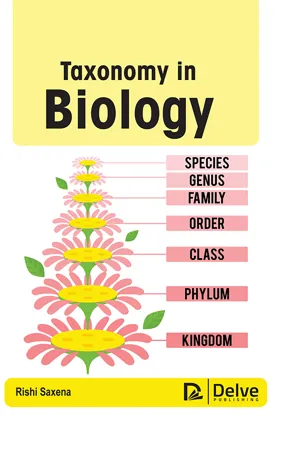

- eBook - PDF

- Rishi Saxena(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Delve Publishing(Publisher)

Biologists, on the other hand, have endeavored to observe all living species with similar thoroughness, resulting in a systematic Taxonomy. A formal categorization serves as the foundation for a general standard and widely known nomenclature, which simplifies cross-referencing and information retrieval. The terms “Taxonomy” and “Systematics” are used differently in biological categorization. According to American evolutionist Ernst Mayer, “Taxonomy is the theory and practice of classifying organisms,” while “Systematics is the science of organism diversity”; the latter, in this context, does have significant interrelationships with evolution, ecology , genetics, behavior, and comparative physiology that Taxonomy doesn’t really. The process of Taxonomy involves two distinct steps: (i) Accurate identification and description of species and its relationships; and (ii) Use of appropriate names for organisms and groupings that contain them. The former is known as classification, which encompasses the analysis of traits as well as the classification of individuals, whereas the latter is known as nomenclature. Taxonomy in Biology 4 1.2. HISTORY OF Taxonomy People who live in close proximity to nature typically have a strong understanding of the local fauna and flora, as well as the ability to recognize several of the larger groups of living creatures (e.g., fishes, birds, and mammals). Its expertise, on the other hand, is situational, and such people very rarely generalize. Nevertheless, the ancient Chinese and Egyptians made some of the first ventures into formal, though restricted, classification. In China, a collection of 365 medicinal plant species served as the foundation for later hydrological investigations. Although the inventory is assigned to the mythological Chinese emperor Shennong, who lived around 2700 years ago, it was most likely composed around the turn of the century. - eBook - ePub

Handbook of Biological Control

Principles and Applications of Biological Control

- T. W. Fisher, Thomas S. Bellows, L. E. Caltagirone, D. L. Dahlsten, Carl B. Huffaker, G. Gordh(Authors)

- 1999(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

In the following chapter, we develop lines of reasoning intended to show the importance of Taxonomy to biological control and illustrate instances where taxonomic work has been vital in the success or occasionally responsible for the failure, of biological control programs. We delineate areas of responsibility in collaboration between biological control workers and taxonomists. Finally, we note the importance of voucher specimens to the future success of biological control programs; and the collation of biological information about hosts, prey, and their natural enemies.Taxonomy: THE HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Taxonomy has a pervasive influence on all human activities. The urge to arrange, organize, describe, name, and classify seems fundamental. This urge operates at all levels of social organization, from the alphabetical arrangement of family names in the telephone directory to the development of legends for street maps. In a very real sense, a world without organization cannot be imagined. These efforts at organization, protracted over time, have been called Taxonomy or systematics. In biology, Taxonomy is the branch that deals with the description of new taxa and the identification of taxa known to science. Classification involves the arrangement of taxa based on morphological and biological characteristics.Beginning with the ancient civilizations, names have been applied to organisms. Insects were apparently among the objects of naming because Beelzebub, of biblical reference, was (among other things) “lord of the flies.” These so-called “common” names of many organisms are in widespread usage today, thus testifying to the utility of such a practice. Despite the usefulness of common names to the layman, several problems are inherent in common names. Most serious of these problems is synonymy. Frequently, more than one common name is applied to a single organism (synonyms), or the same common name is used for different organisms (homonyms). Synonymy has created confusion and misunderstanding because the biological characteristics and habits of similar organisms can be profoundly different.In its earliest form, the scientific name given to an organism was often impractical and unwieldy. Scientific names during the lifetime of John Ray (= Wray) (1628 to 1705) consisted of a series of Latin adjectives catenated in such a way as to describe the animal. The system was less ambiguous than the common name system, but it had the problem of being cumbersome because the name of an animal frequently was several lines or a paragraph long. Thus, to mention the scientific name of an animal in conversation required an excellent memory and plenty of time. - eBook - PDF

Semantics in Business Systems

The Savvy Manager's Guide

- Dave McComb(Author)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- Morgan Kaufmann(Publisher)

However, our made-up taxonomies rarely have this kind of rigor. The biologic Taxonomy is consistent in its use of the link meaning “is a kind of.” A Taxonomy that is consistent in this way is powerful, because the application can imbue items lower in the Taxonomy with attributes higher in the Taxonomy. Often the most useful taxonomies are the simplest. My experience is that, with the exception of the biologic Taxonomy, as a Taxonomy grows its integrity shrinks. So one suggestion is to keep taxonomies small, single purposed, and orthogonal (see definition earlier in this chapter). A powerful Taxonomy has the following characteristics: • An item categorized to a lower-level category is also a member of all its category parents. • An item categorized to a category may also be treated as one of its supertypes (although it needn’t be). • There should exist some set of rules that would allow a classifier to determine whether any of the subcategories are appropriate (we call these “rule in/rule out” criteria). Taxonomies: Ordering a Vocabulary 55 14. Cladistic analysis is a technique for determining the relatedness of species from their DNA and other clues, rather than from their physiologic features alone. In the linguistic study of semantics, words or concepts that are related by the “inclusion” relationship (the “isa” relationship) are called hyponyms. Hyponymy is a good basis for taxonomies, because all of the subsumed con-cepts can still be treated as the parent. However, taxonomies do not have a rich enough semantic for most of our uses. That is where ontologies come in. Ontology: A Web of Meaning Tom Gruber was affiliated with Stanford University when he penned this oft-cited definition of an ontology: Ontology “An ontology is a specification of a conceptualization.” 15 Gruber points out that ontology has a rich history in philosophy, where it deals with the subject of existence and is often associated with epistemology. - eBook - PDF

Chemistry in Botanical Classification: Medicine and Natural Sciences

Medicine and Natural Sciences

- Gerd Bendz(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

For example, Birch [1] in a paper delivered at the IUPAC symposium in Stras-bourg in July 1972 on Chemistry in evolution and systematics writes: Attempts have been made to assist that essentially artificial classifi-cation, Taxonomy, by considering the structures of plant constituents as markers on a level with morphological characteristics. Ignoring the fact that I do not understand what this com-ment means as written, two of the key words used are classification and Taxonomy, and other terms to be considered include systematics, rela-tionships, phylogeny, phenetic, phyletic/phylo-genetic, evolutionary (as applied to systems of or approaches to classification and relation-ships). I assume that the title of this symposium is not to be understood literally, as classification is but one aspect of the general field of sys-tematics and consequently of biochemical sys-tematics (if such a term is admitted, see below for discussion). Definitions (a) Systematics. In the broadest sense, system-atics is concerned with the scientific study of the diversity and differentiation of organisms and the relationships (of any kind) that exist between them [2, 3]. Without further qualifica-tion (other than botanical/zoological/fungal/ microbial, etc.) it embraces phylogenetic, evo-lutionary, phenetic, morphological, traditional, classical, etc. approaches. It can cover such Nobel 25 (1973) Chemistry in botanical classification 42 V. H. Heywood studies at all levels in the hierarchy, ranging from the individual and population level to the family, order, class and even higher levels. At the lower levels of the hierarchy, it includes what is often called biosystematics and indeed Solbrig's recent text book entitled Plant bio-systematics [4] is, in effect, a contribution to plant systematics. - eBook - PDF

- Kostas Kampourakis, Tobias Uller(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

what is the basis of biological classification? 217 be counted as a new species or as a variety of a species that is already known, and so on. But such practical problems have a specific theoret- ical context and history. They are connected to a persistent lack of clarity regarding what aspects of nature biological classifications are supposed to represent, as well as to debates regarding the meaning of many core terms that feature in biological classifications (such as “species” and “gene”), and to how these concepts have changed as biology developed as a science. Practical problems in classifying organisms partly arise because it is unclear which criteria we should use to group individual organisms into species and to delimit species from one another. The same holds for questions about genetic diversity, where biologists disagree on what segments of DNA count as genes, and how these are best grouped into gene families and so on. History and philosophy of science are important here, because they illuminate the historical background and the theor- etical context of many problems that working scientists are confronted with in their daily practice. This is one reason why history and philoso- phy of science are important for working biologists, for biology educa- tors, and for anyone who wants to understand how biology as a science works and what the nature is of the knowledge that it produces about the living world. In what follows, I illustrate this by examining two cases of biological classification: the classification of organisms into species and other taxa, and the classification of genes into kinds. I focus on what a natural system of classification actually is; the assumption that there is a nat- ural order in the living world; the conceptual difficulties surrounding the classificatory concepts of “species” and “gene”; and the theory- dependence of classifications. - eBook - PDF

- David Briggs, S. Max Walters(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

19 The taxonomic challenge ahead We live in a species-rich world that is increasingly under human influence. As we have seen in earlier chapters, there is abundant evidence that many species are endangered, and this includes unknown organisms that have yet to be named and classified. If we are to appreciate the true extent of biodiversity, there is a formidable and urgent taxonomic task ahead (Mallet & Willmott, 2003; Bateman, 2011). What are the prospects of the completion of a catalogue of life? The challenges are discussed by Wheeler (2008), who comes to the conclusion that, at the very point in history where a major effort is required of taxonomists, there is a growing concern that Taxonomy has suffered a ‘decline in prestige and support’. As we have seen in earlier chapters, Taxonomy has a very long history. Wheeler considers that two twentieth-century developments, in particular, have challenged the status, funding and prospects of taxonomic studies. We have seen in earlier chapters that, in the 1920s and 1930s, biologists became increasingly interested in experimental and genetic investigations of evolutionary patterns and processes. Many botanists, initially trained as taxonomists, turned to these investigatory studies to study intraspecific variation, speciation etc. These approaches became known as Experimental Taxonomy or Biosystematics. Huxley (1940) in his classic book New Systematics hoped for the rise of an integrated subject, but Wheeler points out that some biologists, enthusiastic for the emerging specialisms, came to believe that Taxonomy, being ‘non-experimental’, was not really a science, but was involved with ‘subjectively naming and classifying species’. Thus, ‘Taxonomy involved arbitrary bookkeeping and pigeonholing practices and legalistic wrangling over scientific names, while systematics was experimental and intellectually exciting and expansive’. - eBook - PDF

- James Maclaurin, Kim Sterelny(Authors)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- University of Chicago Press(Publisher)

This history is in many ways an attempt to build a Taxonomy that recognizes and integrates shared histories with phenotype similarities. No stable solution has been found. Current practice sacrifices phenotype similarity and uses shared history as its basis for identifying taxa. But that is not because phenotypes are unimportant. The search for natural classification systems in biology has turned out to be diffi cult, because biological individuals are marked by both their history and their environment. It has proved to be diffi cult (ar-guably impossible) to incorporate both influences on causal profiles within the one system of classification. If there were a single natural Taxonomy for biology, the biodiversity problem would be more trac-table. We could unequivocally identify the natural elements from which biological systems are composed, and their important similarities and differences. Defining diversity would still not be easy; some systems would be diverse because of the number of distinct elements in them and others because of the differences between those elements, and so we would have to weight differentiation against number. But as we shall see, the quest for natural taxonomies in biology has been diffi cult, and that exacerbates the problem of defining diversity. Evolutionary Taxonomy’s Uneasy Compromise By the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species , in 1859, the Lin-naean system was already in wide use in biology. The basic Linnaean move was to introduce the binomial system, with species being grouped into genera, each of which consists of a cluster of similar species. But it was elaborated into a deeper hierarchical system: a cluster of similar genera is a family; a cluster of families is an order, and so on up the taxo-nomic hierarchy. This system was one of several nineteenth-century systems of Taxonomy based upon elaborate patterns that, given a cer-tain amount of charity, were there to be found in nature. - eBook - PDF

- T Swain(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Whatever m a y be said now in criticism of the Linnaean system, it is inconceivable t h a t it should be displaced in the near future as the main reference framework for the higher groups of organisms; too much intellectual capital has been sunk in it, and in any case it m a y be doubted whether any other form of investment would yield better returns in the form of service to biology in general. The function of the current version of the classical system is guarded b y the International Codes of Nomenclature. The important passage in the Botanical Code (1956) governing the use of the species category are Articles 2 and 23. Article 2 states t h a t E v e r y plant is to be treated as belonging to a number of taxa of consecutively subordinate ranks, among which the rank of species (species) is basic, and Article 23 con-tains the sentence, T h e name of a species is a binary combination con-sisting of the name of the genus followed by a single specific epithet. The taxonomic species is thus the category to which all plants must be referred for the purposes of naming and classification. This is all the defi-nition of it possible, or indeed required; and the nomenclature commit-tees of successive International Congresses have wisely re-asserted the principle t h a t it is no part of their duty to attempt any biological defini-tion of this or any other taxonomic category. The strength of this parti-cular species concept lies in the fact t h a t it predicates no special kind of variational unit, since the absence of any rigid specification permits Linnaean binomial nomenclature to be extended to all groups. Or perhaps it might be more logical to say t h a t because it is generally agreed t h a t the binomial system should be extended to all groups, the necessary corollary is t h a t the species category to which it is applied cannot be defined exclusively in terms of the variation pattern in any one group. - Michael Ruse(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

While his artificial classes and orders of flowering plants made botany accessible for beginners, he had insisted that skillful naming is the job of an expert, someone with wide enough experi- ence and sound enough understanding to recognize natural kinds of organisms, the entities now called taxa. The word “taxon” was introduced in the twentieth century to clarify the distinction between “species” as a concept or category and It is a truly wonderful fact – the wonder of which we are apt to overlook from familiarity – that all animals and all plants throughout all time and space should be related to each other in group subordinate to group, in the manner which we everywhere behold – namely, varieties of the same species most closely related together, species of the same genus less closely and unequally related together, forming sections and sub-genera, species of distinct genera much less closely related, and genera related in different degrees, forming sub-families, families, orders, sub-classes, and classes. One of the virtues of his theory, he claimed, is that it can explain this “wonderful fact,” which otherwise is mysterious (Fig. 6.1). That claim has two elements: first, the hierarchical structure of classification inherited from Linnaeus expresses essential relationships among organisms; and, second, the alternative theory gives no explanation. Both claims are roughly, but not exactly, true. Because it is roughly true that the Linnaean hierarchy corresponds to what we may call the shape of nature, Darwin Figure 6.1. The classificatory system of Carl Linnaeus (1707–78). It is a series of nested sets (taxa), getting ever-more inclusive as one moves up the hierarchy (categories). M a ry P i c k a r d W i n s o r G 74 g be a cheering prospect; but we shall at least be freed from the vain search for the undiscovered and undiscoverable essence of the term species” (Darwin 1859, 485).- eBook - PDF

- David N. Stamos(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- SUNY Press(Publisher)

21 Chapter 2 Taxon, Category, and Laws of Nature As pointed out earlier, in the literature on the modern species problem arguably the most fundamental distinction is between species as a taxon and species as a category. Species taxa are particular species and are given binomial names such as Tyrannosaurus rex and Homo sapiens. It is species taxa that evolve, that speciate, that have ranges, that are broad-niched or narrow-niched, and that become endangered or extinct. The species cate- gory, on the other hand, is the class of all species taxa. The species problem is typically phrased in terms of determining the on- tology of species taxa. But the species category is also a problem. Some con- ceive of it as an abstract class, a class captured by a definition, the definition determining (or capturing) membership in the class, such that the class (along with its definition) stays the same through time as particular species taxa come and go in terms of existence. Others, however, conceive of the species cate- gory not as an abstract class but as a concrete set, simply the set of all species taxa (for examples of both views, cf. Stamos 2003, 150, 258). This latter view, however, that the species category is a set rather than a class, has serious problems typically overlooked by its advocates. Granted, it has greater parsimony, since the species category simply is its member taxa and nothing more. But this view comes at a great cost. For one thing, it can- not possibly capture the sense of the species category remaining the same while its member taxa come and go. If the species category is simply a set, then as a set it changes every time a species taxon comes into existence or goes out of existence. If the species category is viewed as an abstract class, on the other hand, it does not have this problem. - eBook - PDF

Cladistics: Perspectives on the Reconstruction of Evolutionary History

Papers Presented at a Workshop on the Theory and Application of Cladistic Methodology, March · 22–28, 1981, University of California, Berkeley

- Thomas Duncan, Tod F. Stuessy, Thomas Duncan, Tod F. Stuessy(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Columbia University Press(Publisher)

13 Considerations in Formalizing a Classification RAYMOND B . PHILLIPS Classification, followed by the application of names, is an essential part of human thought and communication. It is an activity that summarizes ob-served patterns. The best classifications are those that are based on the largest possible pool of information evaluated by a means appropriate to the use to be made of the classification, thus conveying the largest amount of in-formation. In botanical classification, the work of such pre-Darwinians as Jussieu (1789) and Candolle (1813) resulted in classifications commonly referred to as natural in many introductory plant Taxonomy textbooks (e.g., Ben-son 1979; Jones and Luchsinger 1979). These systems, particularly at the generic and familial ranks, were based on a large assortment of characters observed in the plants, and groups were defined by the observed similari-ties among them. Most of the changes found in classifications since then at these ranks have been primarily the result of the acquisition of a large amount of new data (see Engler and Prantl 1898; Takhtajan 1969; Cronquist 1981). The impact of evolutionary theory on biological classification has been pri-marily as a means of explaining the patterns of similarity that are observed and incorporated in the classifications, rather than directly affecting the classifications. Evolutionary theory has had so little impact because the same operational approach has been used throughout most of the recent history of classification. Namely, similar organisms are grouped together, the gaps between groups of organisms, as evidenced by the distribution of character states, providing the basis for the classification. The recognition of such groupings and gaps does not require evolutionary theory, although they may be interpreted in an evolutionary context. One of the strongest and most explicit statements in support of this approach is that of McNeill (1979): - eBook - PDF

The Taxobook

Principles and Practices of Building Taxonomies, Part 2 of a 3-Part Series

- Marjorie Hlava(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Springer(Publisher)

Guidelines for constructing taxonomies and thesauri recommend creating terms using natural language designed for post-co- ordination. Following this method also supports automated indexing and text mining. 2.3 A FEW TYPES OF TAGGING 22 2. Taxonomy BASICS 2.4 TAXONOMIES AND HIERARCHICAL STRUCTURE As previously mentioned, taxonomies are one kind of controlled vocabulary. What distinguishes them from ordinary term lists is the presence of hierarchical relationships, with the conceptually broadest terms at one level (often referred to as the “Top Terms”), “narrower terms” grouped under the top terms, and yet narrower terms similarly grouped under those terms, with the pattern con- tinuing until the most specific terms are reached. In the standard mode of hierarchical display, the narrower terms are underneath and indented to the right of their respective “broader terms”: • Computer equipment º Printers º Laser printers º Inkjet printers º Dot matrix printers • Monitors º Flat screen monitors º Touch screen monitors Most of us are familiar with hierarchical structure in document outlines and some tables of contents. We also know them from genus-species relationships in biologic taxonomies or par- ent-child relationships forming a full genealogy. One example of a Taxonomy-like outline is shown below. It’s from the Wikipedia article “Outline of knowledge [13].” Knowledge of humankind • Humanities º Classics º History • Language º Literature º Performing arts • Dance • Music • Theatre º Philosophy 23 º Religion º Visual arts • Media type • Painting • Science º Natural Sciences • Astronomy • Biology • Chemistry • Earth Sciences • Physics º Social Sciences • Anthropology • Economics - Trade • Education • Geography • Health • Law - Jurisprudence • Linguistics • Political science • Psychology • Sociology º Applied sciences • Agricultural science 2.4 TAXONOMIES AND HIERARCHICAL STRUCTURE

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.