Biological Sciences

Control of Body Temperature

The control of body temperature refers to the physiological mechanisms that maintain the body's internal temperature within a narrow range, typically around 98.6°F (37°C). This process involves the coordination of various systems, including the nervous system, endocrine system, and skin, to regulate heat production and loss. Key components of temperature regulation include shivering to generate heat and sweating to dissipate heat.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Control of Body Temperature"

- eBook - PDF

Human Thermal Environments

The Effects of Hot, Moderate, and Cold Environments on Human Health, Comfort, and Performance, Third Edition

- Ken Parsons(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Not only does the body maintain an internal temperature at around 37°C, but it also maintains cell temperatures all over the body at levels which avoid damage. Regulating processes operate within the cells and it is the way in which the whole body regulates all cell temperatures that make up the system of human thermoregulation. Bligh (1985) suggests ‘the constancy of every living cell relative to that of its immediate, and also more remote, environments, requires a mass of regulator processes’ and that ‘a dif-ficulty in any study of biological homeostasis or regulation is that in even the simplest unit of life, the cell, the stabilising processes are so numerous and interrelated that it can be difficult to determine what principle underlies the stabilising function’. Although the sum of the parts make up the whole (or greater), at the level of the ‘whole body’ it can be argued that there is a central regulating system. There have been numerous studies of this system and a detailed discussion is given by Hensel (1981) and Bligh (1985). For most practical purposes it is useful to consider a simple engi-neering analogy, although, as Hensel (1981) points out, ‘analogies from technology 65 Human Thermal Physiology and Thermoregulation may be misleading since the principles actually used by control engineers are only part of the theoretical possibilities of control systems’. There has been some dispute about what is the regulated variable in thermoregulation. Bligh (1978) considers this and concludes that evidence suggests that temperature or a function of various tem-peratures is the controlled variable, as opposed to such ideas that body heat content is the controlled variable (Houdas et al., 1972; Houdas and Guicu, 1975) or that the rate of heat outflow is adjusted to balance metabolic heat production (Webb et al., 1978). - Liana Bolis, Julio Licinio, Stefano Govoni(Authors)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

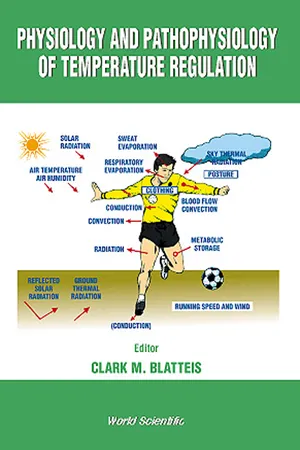

247 7 The Autonomic Nervous System and Thermoregulation Quentin J. Pittman University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada The thermoregulatory system is a controlled system requiring sensors, a con-troller, and effectors. Sensation of temperature occurs in the skin, deep body tis-sues, and within the central nervous system (CNS) through specialized thermore-ceptive fibers and neurons. Information about body temperature is integrated and compared to a reference temperature. This function is distributed in a number of CNS sites but is most highly concentrated in the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus utilizes endocrine, behavioral, and autonomic outputs to alter heat flow to the en-vironment and to alter heat production. These functions are mediated by sympa-thetic fibers to a number of end organs, including vascular smooth muscle, sweat glands, and brown adipose tissue, and by outputs to both respiratory and skeletal muscles. There is a close relationship between the thermoregulatory system and the control of metabolic rate for purposes of body weight regulation. Under envi-ronmental extremes or in the case of pathology, hypothermia or hyperthermia may result. These conditions, which represent a breakdown of normal thermoregula-tory control, are in contrast to fever, which is a regulated elevation of body tem-perature in response to cytokines and which is thought to be useful to the individ-ual in fighting disease. An additional possible beneficial effect of altered body temperature is in the case of controlled hypothermia as a treatment for ischemic brain injury. I. INTRODUCTION Our body temperature is precisely regulated. The stability of this regulation is widely appreciated; even those individuals not scientifically trained are usually aware that body temperature rests at approximately 37°C. Furthermore, deviations from this temperature have important diagnostic implications.- Clark M Blatteis(Author)

- 1998(Publication Date)

- World Scientific(Publisher)

6 Physiology and Pathophysiology of Temperature Regulation In his concept of le milieur interieur, Claude Bernard placed the emphasis upon the protection furnished living cells by the nearly constant composition and temperature of the fluids which bathe them. "All the vital mechanisms, varied as they are, have only one subject, that of preserving constant the conditions of life in the internal environment. The fixity of the milieu supposes a perfection of the organism such that the external variations are at each instant compensated for and equilibrated. Therefore, far from being indifferent to the external world, the higher animal is on the contrary constrained in a close and masterful relation with it, of such fashion that its equilibrium results from a continuous and delicate compensation established as if by the most sensitive of balances. All of the vital mechanisms however varied they may be, have always but one goal, to maintain the uniformity of the conditions of life in the internal environment." (translated from the French) In the very simplified model of temperature regulation described here, of particular importance is what determines the actual body temperature and how is it controlled in man at around 37.5 °C. As in most physiological processes, a stimulus is received and a response is initiated. In temperature regulation, thermosensitive neurones that have thermosensitive receptors (nerve endings) and which are present in the periphery, in deep organs of the body and in the central nervous system, respond to changes in temperature. So called 'cold sensitive' neurones increase their firing rates as temperature falls, and 'heat sensitive' neurones increase their firing rates as temperature rises.- eBook - PDF

Temperature and Toxicology

An Integrative, Comparative, and Environmental Approach

- Christopher J. Gordon(Author)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

13 Chapter 2 Principles of Temperature Regulation 2.1 INTRODUCTION It was not until the advent of the small mercury thermometer in the 19 th century that physiologists could begin to study thermoregulation. It was recognized that, among all animal life, relatively few species can be consid-ered as true temperature regulators, meaning that they regulate their body temperature within narrow limits under a wide range of external and internal heat loads and heat sinks. Temperature regulators use autonomic and/or behavioral motor responses, termed thermoeffectors , to defend their body temperature against changes in heat gain and heat loss to the environment as well as the heat production from exercise. With some exceptions, all invertebrates are considered to be temperature conformers , meaning they lack any behavioral or autonomic mechanisms to regulate temperature inde-pendently of ambient temperature. The body temperature of most temper-ature conformers is almost always equal to that of the ambient conditions. All animal life is essentially capable of responding to thermal stimuli and eliciting a corrective motor response. Even unicellular organisms exhibit thermotropism and will move toward or away from a thermal stimulus. 2.2 TERMINOLOGY Toxicologists desiring a better understanding of how temperature affects their particular biological endpoint will find a variety of terms in the 14 Temperature and Toxicology literature to describe the thermoregulatory characteristics of a species. There is often overlap in definitions that can create confusion for both trained thermal physiologists and specialists in other fields of biology and medicine (Table 2.1). The study of temperature regulation is conventionally divided into two broad categories: tachymetabolic species, including birds and mammals, have a high basal metabolic rate; bradymetabolic species, including reptiles, amphibians, fish, and invertebrates, have a relatively low basal metabolic rate. - eBook - PDF

Principles of Biological Regulation

An Introduction to Feedback Systems

- Richard Jones(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

In addition to the three mechanisms men-tioned above, there are other processes that aid in temperature regulation in man and other species, such as hormonal control of metabolism, panting, and behavior patterns. These factors can be controlled in labora-tory studies, but in the absence of such controlled experiments the interpretation of such observations is extremely difficult. e. So far, we have mentioned only those processes having an im-mediate bearing upon temperature regulation, but it must be noted that other homeostats also may be intimately involved. Chief of these are the cardiovascular system and respiration, each of which has a direct con-nection with thermogenesis, heat transport, or heat loss. One quickly concludes that temperature regulation, and without doubt most of the other homeostats, are coupled to each other in a variety of ways, which makes their individual study very difficult. 8.3 TEMPERATURE REGULATING MECHANISMS IN MAN 253 25 30 35 tongue temperature ( b ) Fig. 8-3. Neural pulse frequencies in fibers from temperature receptors in the cat. (a) Single fibers in the skin (Hensel, Iggo, and Witt, 1960). (b) Fiber bundles in the lingual nerve (Hensel and Zotterman, 1951). 254 8 DISTINCTIVE FEATURES OF HOMEOSTATIC SYSTEMS Temperature Receptors: Fig. 8-3 8.4 a. Homeostatic systems usually contain neural receptor units, the function of which is to measure a specified variable and provide a neural signal that can be used for control and regulation purposes. This section describes the temperature receptors and some of their distinctive properties (Hensel, 1963). b. Specific temperature receptors are identified as such by virtue of their high sensitivity to temperature change, as well as a high threshold for mechanical stimulation. These are tonic units in which the pulse fre-quency is maintained for long periods at a value proportional to the temperature stimulus. - O.G. Edholm(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER 3 Thermal Physiology O.G. Edholm and J.S. Weiner Body Temperatures and Gradients 112 Components of Control (Shivering, Sweating, Circulation) 114 Thermoregulatory Functioning 120 The Central Controller 129 Heat Balance Equation 135 Thermal Exchange Equations 145 Acclimatization 150 Exercise 157 Salt and Water Balances 164 Comfort 166 Behaviour 170 Clothing 170 Temperature and Performance 175 Hypothermia 176 Heat-Induced Disorders 179 A fundamental property of man in common with mammals generally is his homeothermy—the ability and necessity to maintain internal body tem-perature within narrow limits. The survival value of a constantly main-tained high temperature to the homeotherm is very evident; it imparts freedom from the dominance of external temperature and permits a high level of muscular, neuronal and cellular activity. Analysis of this property entails the understanding of (a) the nature, significance and limits of the 111 112 O.G. EDHOLM AND J.S. WEINER homeothermic state, (b) the functioning of the homeothermic control system and its components, and (c) the thermal exchanges involved in the maintenance of the homeothermic state. From a knowledge of the control system and the associated thermal exchanges it is possible to specify the thermal behaviour of the human body under a wide variety of environ-mental conditions taking into account such factors as work and clothing. As will become apparent, specification or prediction of the thermal state can be quantitatively fairly precise but there are limitations imposed by the complexities of bodily configuration as well as factors affecting the sensi-tivity and rate responses of the control system and its components.- eBook - PDF

Minder Brain, The: How Your Brain Keeps You Alive, Protects You From Danger, And Ensures That You Reproduce

How Your Brain Keeps You Alive, Protects You from Danger, and Ensures that You Reproduce

- Joe Herbert(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- World Scientific(Publisher)

Eds. E Schonbaum, P Lomax, pp. 53–183. ( Pergamon Press, New York) A homeostatic regulation implies regulated level of some variable that is sensed by the central nervous system. In control system terminology, that regulated level is called a ‘setpoint’. In thermoregulation, that implies a set, or reference, or optimal body temperature against which actual body temperature is compared. If there is a discrepancy between the two, an error signal is generated which activates heat loss or heat production mechanisms to return actual body temperature closer to set temperature. The comparator, or signal mixer that compares the two, in other words the thermostat, has been localized in the hypothalamus . . . . E Satinoff. (1983) A re-evaluation of the concept of the homeostatic organization of temperature regulation. In: Handbook of behavioral neurobiology . Eds. E Satinoff, P Teitelbaum, 6 , pp. 443–472. (Plenum Press, New York.) Deep hibernation. . . is homeostasis in slow motion. C P Lyman. (1990) Pharmacological aspects of mammalian hibernation. In: Thermoregulation . Physiology and biochemistry. Eds. E Schonbaum, P Lomax, pp. 415–436. (Pergamon Press, New York.) that we do not really know why there has been such evolutionary pressure for 37 ° C; why not 42 ° ? Or 25°? There have been a number of theories (of course), but none is really entirely convincing. Most of them argue either that 37°C is the optimum for chemical reactions in the body to take place, or that 37°C is the easiest body temperature to maintain in an ambient one of around 25°C, which is the average air temperature in regions where mammals are thought to have evolved. The reason why mammals need to keep their internal temperature (usually called ‘core temperature’) constant is rather easier to understand. The mammalian body is a vast collection of chemical reactions, most of them depending on enzymes. Enzymes act as catalysts: that is, they enable other chemical reactions to occur. - eBook - PDF

- Stephan A. Mayer, Daniel I. Sessler, Stephan A. Mayer, Daniel I. Sessler(Authors)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Sessler 2 REVIEW Thermoregulation Body temperature is among the best regulated physiological parameters, rarely deviating by more than a few tenths of a degree Celsius. It is better regulated, e.g., than either heart rate or blood pressure. Core temperature deviations of even a couple of degrees Celsius in either direction are associated with complications (4–8). However, known complications fail to explain why mammals expend considerable effort to regulate temperature to within a few tenths of a degree. For example, it is not obvious why the body would regulate core temperature to a precision of tenths of degree when the normal circadian temperature approaches 1jC (15,16). However, similarly precise control is maintained in most species. It thus seems logical to assume that core temperature is well controlled for compelling physiological reasons—even if the reasons are not yet apparent. Afferent Input There are temperature-sensitive cells throughout the body, including the skin surface. Cold-sensitive cells increase their firing rate as they cool, whereas warm-sensitive cell do the opposite. Both are phenomenally sensitive. Human skin, e.g., can detect temperature changes of as little as a few thou- sandths of a degree Celsius (17). Cold signals travel primarily via AB nerve fibers and warm information by unmyelinated C fibers, although there is some overlap (18). The C fibers also detect and convey pain sensation, which is why intense heat cannot be distinguished from sharp pain. Most ascending thermal information tra- verses the spinothalamic tracts in the anterior spinal cord. With the exception of the skin surface (19), relative importance of thermal input from various regions of the body is difficult or impossible to determine. - eBook - ePub

Contributions to Thermal Physiology

Satellite Symposium of the 28th International Congress of Physiological Sciences, Pécs, Hungary, 1980

- Z. Szelényi, M. Székely(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Pergamon(Publisher)

Strieker, E. M., Zigmond, M. J.Sprague, J.M., Epstein, A.N., eds. Progress in Psychobiology and Physiological Psychology; Vol. 6. New York, Academic, 1976:121–188.Teitelbaum, P., Epstein, A. N. Psychol. Rev. 1962;69(74).Thauer, R. Pflügers Arch. 1935;236(102).Thauer, R. Ergebn. Physiol. 1939;41(607).Toth, D. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1973;82(480).Van Zoeren, J. G., Strieker, E. M. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1977;91(989).Wit, A., Wang, S. C. Am. J. Physiol . 1968; 215:1–1151.Wiinnenberg, W., Brück, K. Nature. 1968;218(1268).Wiinnenberg, W., Brück, K. Pflügers Arch. 1968;299(1).Wiinnenberg, W., Brück, K. Pflügers Arch. 1970;321(233).Wiinnenberg, W., Hardy, J. D. J. Appl. Physiol. 1972;33(547).Zeisberger, E., Brück, K. Pflügers Arch. 1971;322(152).Passage contains an image

CNS Control of Body Temperature

JOHN T. STITT, John B. Pierce Foundation Laboratory, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut 06519, USAPublisher Summary

This chapter discusses the central nervous system (CNS) Control of Body Temperature. There is a multiplicative interaction between peripheral and central thermoreceptor inputs in the control of thermogenesis and perhaps other thermoregulatory effector outputs in mammals. Jacobson and Squires proposed a multiplicative relationship between ambient temperature and preoptic temperature in the regulation of oxygen consumption in cats. Bruck and Schwennicke demonstrated with the hyperbolic function that such a relationship existed between skin temperature, measured subcutaneously, and hypothalamic temperature in the control of nonshivering thermogenesis in the guinea pig. A similar type of control over heat production in the harbor seal has also been shown by Hammel et al . The chapter discusses a model that was proposed for the control of cold-induced thermogenesis in a rabbit. This model was predicated on a multiplicative interaction between mean skin temperature (T sk ) and preoptic anterior hypothalamic temperature (T hy ). A distinctive feature of this model is that not only does it predict a decreasing hypothalamic thermosensitivity as the level of T sk is increased but it also predicts that the T hy - eBook - PDF

Heat Loss from Animals and Man

Assessment and Control

- J. L. Monteith, L. E. Mount(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Butterworth-Heinemann(Publisher)

and IRVING, L. (1950a). Biol. Bull. Mar. Biol. Lab., Woods Hole, 99_, 237 SCHOLANDER, P.F., HOCK, R., WALTERS, V. and IRVING, L. (1950b). Biol. Bull. Mar. Biol. Lab., Woods Hole, £9, 259 SCHOLANDER, P.F. and SCHEVILLE, W.F. (1955). J. appl. Physiol., £, 279 SCHWINGHAMER, J.M. and ADAMS, T. (1969). Fedn Proc. Fedn. Am. Socs exp. Biol., _2§/ 1149 STEBBINS, L.L. (1972). Arctic, 25_, 216 THARP, G.D. and FOLK, G.E. Jr. (1964). J. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. , 14_, 255 WEBSTER, A.J.F. (1967). Br . J. Nutr., 2_, 769 WHITTOW, G.C. (Ed.) (1971). Comparative Physiology of Thermoregulation, Vol. II, Mammals, Academic Press, New York WORSTELL, D.M. and BRODY, S. (1953). Mo. Agric. Sta. Res. Bull., No. 515 WYNDHAM, C.H., MORRISSON, J.F. and WILLIAMS, C.G. (1965). J. appl. Physiol. , _2£, 357 8 DAY NIGHT VARIATION IN HEAT BALANCE J. ASCHOFF, H. BIEBACH, A. HEISE and T. SCHMIDT Max-Planck Institut für Verhaltensphysiologie, D-8J3J Erling-Ancle chs, Germany INTRODUCTION Homeothermic organisms are characterised by a deep-body temperature which has a constant long-term mean, but which also usually fluctuates between a maximal and a minimal value once every 24 h. Constancy of temper-ature depends on a balance between heat production and heat loss. In his last review on the regulation of body temperature, Bazett (1949) states: 'The balance is maintained to some extent by control of heat production but for the most part is attained by regulation of heat loss· 1 The predominance of the regulation of heat loss over the regulation of heat production becomes most evident within the zone of thermoneutrality. One could assume that, at least within this zone, the 24-hour rhythm of deep-body temperature also depends largely on a rhythm of heat loss. Surprisingly, however, research in' this field has long been concerned with attempts to discover a rhythm of heat production, and it is only recently that a rhythm of heat loss has been described in detail.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.