Biological Sciences

Endotherm vs Ectotherm

Endotherms are organisms that can regulate their body temperature internally, typically maintaining a relatively constant temperature regardless of external conditions. Ectotherms, on the other hand, rely on external sources of heat to regulate their body temperature and their internal temperature fluctuates with the environment. This distinction is important in understanding how different organisms adapt to and interact with their environments.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

8 Key excerpts on "Endotherm vs Ectotherm"

- No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Academic Studio(Publisher)

Most endothermic organisms are homeothermic, like mammals. However, animals with facultative endothermy are often pokilothermic, meaning their temperature can vary considerably. Similarly, most fish are ectotherms, as all of their heat comes from the surrounding water. However, most are homeotherms because their temperature is very stable. Thermoregulation in vertebrates By numerous observations upon humans and other animals, John Hunter showed that the essential difference between the so-called warm-blooded and cold-blooded animals lies in observed constancy of the temperature of the former, and the observed variability of the temperature of the latter. Almost all birds and mammals have a high temperature almost constant and independent of that of the surrounding air (homeothermy). Almost all other animals display a variation of body temperature, dependent on their surroundings (poikilothermy). Certain mammals are exceptions to this rule, being warm-blooded during the summer or daytime, but cold-blooded during the winter when they hibernate or at night during sleep. J. O. Wakelin Barratt has demonstrated that under certain pathological conditions, a warm-blooded (homeothermic) animal may become temporarily cold-blooded (poi-kilothermic). He has shown conclusively that this condition exists in rabbits suffering from rabies during the last period of their life, the rectal temperature being then within a few degrees of the room temperature and varying with it. He explains this condition by the assumption that the nervous mechanism of heat regulation has become paralysed. The respiration and heart-rate being also retarded during this period, the resemblance to the ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ condition of hibernation is considerable. Again, Sutherland Simpson has shown that during deep anaesthesia a warm-blooded animal tends to take the same temperature as that of its environment. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- White Word Publications(Publisher)

Most endothermic organisms are homeothermic, like mammals. However, animals with facultative endothermy are often pokilothermic, meaning their temperature can vary considerably. Similarly, most fish are ectotherms, as all of their heat comes from the surrounding water. However, most are homeotherms because their temperature is very stable. Thermoregulation in vertebrates By numerous observations upon humans and other animals, John Hunter showed that the essential difference between the so-called warm-blooded and cold-blooded animals lies in observed constancy of the temperature of the former, and the observed variability of the temperature of the latter. Almost all birds and mammals have a high temperature almost constant and independent of that of the surrounding air (homeothermy). Almost all other animals display a variation of body temperature, dependent on their surroundings (poikilothermy). Certain mammals are exceptions to this rule, being warm-blooded during the summer or daytime, but cold-blooded during the winter when they hibernate or at night during sleep. J. O. Wakelin Barratt has demonstrated that under certain pathological conditions, a warm-blooded (homeothermic) animal may become temporarily cold-blooded (poikilothermic). He has shown conclusively that this condition exists in rabbits suffering from rabies during the last period of their life, the rectal temperature being then within a few degrees of the room temperature and varying with it. He explains this condition by the assumption that the nervous mechanism of heat regulation has become paralysed. The respiration and heart-rate being also retarded during this period, the resemblance to the ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ condition of hibernation is considerable. Again, Sutherland Simpson has shown that during deep anaesthesia a warm-blooded animal tends to take the same temperature as that of its environment. - eBook - PDF

- Iosifina Foskolou, Martin Jones(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Actually, all animals are heterotherms because there are regional variations in temperature; this differs among types of tissue, over time, between species, and across ecological niches. Thermoregulation Body temperature (T B ) is maintained by a number of mechanisms, includ- ing behavioural, evaporative, vascular, and metabolic responses; in homeotherms T B is tightly regulated through homeostasis that provides a relative independence of external factors, whereas in ectotherms T B is largely dependent on the thermal environment (Figure 7.2(a)). Body temperature normally fluctuates over the day following circadian rhythms; in humans this reaches a minimum in the early morning and a maximum in the evening, with females on average slightly warmer than males (Figure 7.2(b)). Behavioural thermoregulation is also important: a lizard warming itself up on a stone wall in the morning is effectively Stuart Egginton 142 transitioning between cold blood and warm blood. Other cycles may be present due to hormonal (e.g., the rhythm method of contraception), feeding (due to metabolic cost of digestion), and seasonal (depending on latitude) factors. It is important to recognise that we are endothermic but not isother- mic, i.e., not all of our body is at the same temperature. Heat exchange occurs by physical mechanisms (radiation, convection, conduction, European European Aborigine reptiles, fishes 10 20 30 40 00:00 16:00 0 30 55 Heat prod n Core temp. Core temperature (°C) Environmental temperature (°C) (a) (b) (c) (d) Time of day (h) Time of day (h) Time (h) Core temperature (°C) Core temperature (°C) 80 34 36 38 2 4 6 8 24:00 08:00 06:00 12:00 06:00 00:00 10 20 30 40 36.8 36.6 36.4 36.2 32 36 40 mammals, birds females +20°C 0°C –20°C males Aborigine F I G U R E 7 . 2 Core temperature fluctuates over different timescales. - eBook - ePub

Contributions to Thermal Physiology

Satellite Symposium of the 28th International Congress of Physiological Sciences, Pécs, Hungary, 1980

- Z. Szelényi, M. Székely(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Pergamon(Publisher)

Phylogenic aspects of temperature regulationPassage contains an image

EVOLUTION FROM ECTOTHERMIA TOWARDS ENDOTHERMIA

A.J. HULBERT, Department of Biology, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, N.S.W., Australia, 2500Publisher Summary

This chapter discusses the evolution from ectothermia toward endothermia. Many reptiles have been shown to possess a rate of heating different to their rate of cooling. It has been shown in a variety of lizards that vasomotor control of blood flow is a significant contributor to this difference between rates of heating and cooling. This has also been demonstrated in the tuatara and in turtles. Measurement of local cutaneous blood flow in a lizard has shown it to increase during heating. In view of the variety of reptiles in which it has been reported, it seems almost certain that the pre-mammalian reptiles possessed this vasomotor ability to alter their body conductance. Endotherms have a high level of metabolism compared to ectotherms. The resting mammal that is undergoing no extra expenditure of energy for thermoregulation will have a level of energy metabolism that is four to five times that of a similar sized resting reptile that is at the same body temperature. Mammals may have larger internal organs than reptiles and thus a larger resting metabolism. The reptile–mammal difference in standard metabolism also exists when levels of maximal metabolism are considered.We mammals, with our relatively constant body temperature possess one of the finest examples of physiological homeostasis being favoured by evolutionary selection. This review will concern itself with the evolutionary sequence in which the many different mechanisms that allow mammals to maintain a constant body temperature have occurred. It is limited to mammals and will also not be concerned with the evolutionary history of the central control of body temperature. Basic thermo-regulatory control is much older than the mammals, since ectothermic vertebrates have both thermal detectors and a central nervous system activator (Hammel 1968). - eBook - PDF

Temperature and Toxicology

An Integrative, Comparative, and Environmental Approach

- Christopher J. Gordon(Author)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

The study of temperature regulation is conventionally divided into two broad categories: tachymetabolic species, including birds and mammals, have a high basal metabolic rate; bradymetabolic species, including reptiles, amphibians, fish, and invertebrates, have a relatively low basal metabolic rate. Tachymetabolic species are also termed endot-herms , because they regulate body temperature primarily through internal heat production derived from the sum of all metabolic processes. Many bradymetabolic species are ectotherms , meaning that body temperature is regulated behaviorally by modulating the heat transfer between the body and environment. Homeothermy and poikilothermy are also frequently used terms that classify species into those that maintain their body temperature within a narrow and wide range, respectively. These terms often lose their strict definition depending on the environmental circumstances. This is espe-cially relevant in small mammals dosed with drugs or toxicants. In the glossary of terms for thermal physiology (IUPS, 2001), homeothermy is defined as “the pattern of temperature regulation in a tachymetabolic species in which core temperature…is maintained within arbitrarily defined limits despite much larger variations in ambient temperature.” Poikilothermy, defined as “large variability of body temperature as a function of ambient temperature in organisms without effective autonomic temperature regulation,” is usually equivalent to temperature conformity. Table 2.1 Common Thermoregulatory Terms Term Often Equated to Phyla Exceptions Homeotherm Endotherm, tachymetabolic, temperature regulator, warm-blooded Birds, mammals Torpor in small rodents and birds Poikilotherm Ectotherm, bradymetabolic, temperature conformer, cold-blooded Reptiles, amphibians, fish, invertebrates Endothermy in honeybees and some fish and reptiles Hibernator Mammals Torpor Birds, mammals Heterotherm Birds, mammals - eBook - PDF

- Donald Davies(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

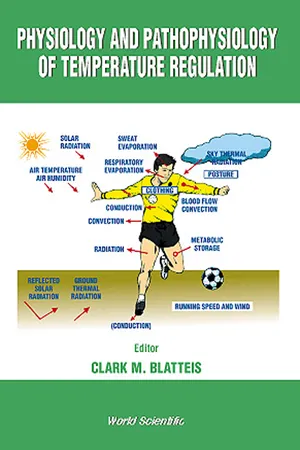

But there are striking differ-ences of detail, and it is these differences that attract our attention to these animals. Because of the diversity of adaptations, there is great diversity in the expression of the basic respiratory pattern. In this chapter particular emphasis has been placed on the adaptation to temperature, because this is what, above all, sets the ectotherms apart from the en-dotherms. From this we learn that acid-base control occurs along a temperature continuum and that we mammals are specialists residing within a narrow band on the continuum. What we have long regarded as the prime regulated variables of the respiratory control system, [H + ] and P C o 2 > a r e revealed by the study of ectotherms to be of secon-dary importance to some more basic homeostatic variable, such as protein ionization. These specialized adaptations of the ectotherms, to temperature and to other environmental stresses, provide us with valuable experimental models and tools not only for understanding and appreciating how such physiological systems can adapt, but affording insights into mammalian control as well. ACKNOWLEDGMENT The support of NSF Grant PCM76-24443 during the writing of this manuscript is grate-fully acknowledged. REFERENCES Adams, W. E. (1958). The Comparative Morphology of the Carotid Body and Carotid Sinus, pp. 194-197. Thomas, Springfield, Illinois. Albery, W. J., and B. B. Lloyd (1967). Variation of chemical potential with temperature. In Development of the Lung (A. V. A. de Reuck and R. Porter, eds.), pp. 30-33. Churchill, London. Austin, J. H., F. W. Sunderman, and J. G. Camack (1927). Studies in serum electrolytes. The electrolyte composition and the pH of serum of a poikilothermous animal at different temperatures. J. Biol. Chem. 72, 677-685. Banzett, R. B., and R. E. Burger (1977). Response of avian intrapulmonary chemoreceptors to venous C0 2 and ventilatory gas flow. - Clark M Blatteis(Author)

- 1998(Publication Date)

- World Scientific(Publisher)

Reptiles, on the other hand, are homeotherms that regulate their T c mainly by behaviorally exchanging heat with their environment; they are called ectotherms. Organisms without effective temperature regulation by neither autonomic nor behavioral means are poikilotherms (e.g., most insects); their T c thus varies as a proportional function ofT a . 3. The "normal" body temperature The heat content of the body can be measured in various ways: 1) as a quantity of heat, specifically as that needed to increase the temperature of 1 kg of water from 15 to 16 °C, i.e., 1 kilocalorie or 1 kilojoule (kilocal x 4.187); 2) as a rate of heat exchange, viz., per unit time and effective heat-exchanging area, i.e., kilocal • h~*- m~ 2 or Watts • m"2 (kilocal • h"*- m"^ x 1.163); or 3) as a degree of sensible heat or cold, reckoned from melting ice to boiling water and expressed on a graded scale, i.e., as temperature (in °C [preferred] or °F). Temperature, of course, is the easiest variable to measure and, consequendy, it is the one most commonly monitored. B-2 B-3 15 16 Physiology and Pathophysiology of Temperature Regulation 3.1 Distribution The temperatures of different sites of the body vary significantly from site to site. Thus, temperatures taken at the surface are considerably different from those measured in an internal region of the body. They also vary depending on the specific body locus, superficial or deep. For example, in an individual at rest, the skin temperature of the trunk is normally higher than that of the arms, and the temperature of the heart is higher than that of the kidneys. However, the temperatures within the body are more uniform and stable over time than those at the surface, which are not uniform and can fluctuate widely and rapidly.- eBook - PDF

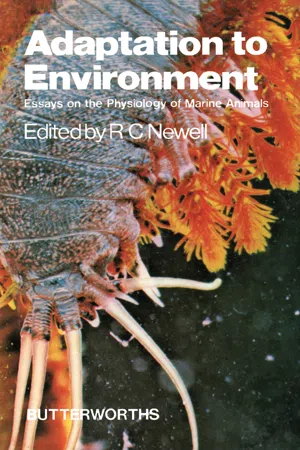

Adaptation to Environment

Essays on the Physiology of Marine Animals

- R. C. Newell(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Butterworth-Heinemann(Publisher)

Less well understood are the mechanisms which help to enable tuna species to maintain their brain and retinal temperatures at levels above ambient (Stevens and Fry, 1971). As we have suggested above, these organs may offer us examples of heat generation mechanisms similar to those found in endothermic insects and mammals. 138 The means by which this control of heat flow is accomplished in warm-bodied fishes such as tuna species (Carey et al., 1971) are illustrated in Figure 3.3. Counter-current heat exchangers, which of course are also present in birds and mammals, all have a common anatomy: warmed blood passing from actively metabolising tissues is brought into close contact with cooled blood arriving from the gills (or, in the case of birds and mammals, from the cooler extremities such as the legs and feet). The bed of fine, closely intertwined capillaries, the rete mirabile, of the heat exchanger permits a rapid and nearly quantitative transfer of heat from the venous circulation to the arterial circulation. BIOCHEMICAL ADAPTATIONS TO TEMPERATURE We now turn our attention to marine species which are unable to regulate their body temperatures through anatomical and physiological means. True ectotherms, which represent the vast majority of marine species and individuals, illustrate the magnitudes and complexities of biochemical adaptations which are required when the chemistry of the cell cannot be shielded against the effects of changes in ambient temperature. 3.4 ECTOTHERMY 3.4.1 Temperature compensation of metabolic rates Ectothermic organisms which are unable to control their cell temperatures often exhibit considerable degrees of temperature-independence in their metabolic rates. Whereas one would predict that each 10°C change in cell temperature would lead to an approximately two-fold change in metabolic rate, this expectation often is not realised, i.e.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.