Biological Sciences

Evolutionary Changes

Evolutionary changes refer to the gradual modifications in the genetic makeup of a population over successive generations. These changes can result from natural selection, genetic drift, mutation, and gene flow, leading to the emergence of new species and the adaptation of existing ones to their environments. Understanding evolutionary changes is fundamental to comprehending the diversity of life on Earth.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

9 Key excerpts on "Evolutionary Changes"

- eBook - PDF

- Mark Ridley(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

As Theodosius Dobzhansky, one of the twentieth century’s most eminent evolutionary biologists, remarked in an often quoted but scarcely exaggerated phrase, “nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution” (Dobzhansky 1973). Evolution means change, change in the form and behavior of organisms between generations. The forms of organisms, at all levels from DNA sequences to macroscopic morphology and social behavior, can be modified from those of their ancestors during evolution. However, not all kinds of biological change are included in the definition (Figure 1.1). Developmental change within the life of an organism is not evolution in the strict sense, and the definition referred to evolution as a “change between genera- tions” in order to exclude developmental change. A change in the composition of an ecosystem, which is made up of a number of species, would also not normally be counted as evolution. Imagine, for example, an ecosystem containing 10 species. At time 1, the individuals of all 10 species are, on average, small in body size; the average member of the ecosystem is therefore “small.” Several generations later, the ecosystem may still contain 10 species, but only five of the original small species remain; the other five have gone extinct and have been replaced by five species with large-sized indi- viduals, that have immigrated from elsewhere. The average size of an individual (or species) in the ecosystem has changed, even though there has been no evolutionary change within any one species. Most of the processes described in this book concern change between generations within a population of a species, and it is this kind of change we shall call evolution. When the members of a population breed and produce the next generation, we can imagine a lineage of populations, made up of a series of populations through time. - eBook - PDF

Tales of the Ex-Apes

How We Think about Human Evolution

- Jonathan Marks(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

53 In chapter 1, I defined biological evolution as the naturalistic production of difference, and differentiated it from some of its homonyms. Stellar “evolution” for example, involves a transfor-mation of state dictated by physical law. A yellow star will prob-ably eventually become a red giant, because that is what stars do when they have run out of hydrogen atoms to fuse. A star’s transformation is highly predictable, and determined by a small number of variables. “Cultural evolution” may involve the direct and conscious production of solutions to environmental prob-lems. And the “evolution” by which an embryo is eventually transformed into a geezer is determined neither by physical law nor by the need to survive, but by the enactment of a genetic program, itself the product of eons of evolution, but which encodes a life cycle. None of these is what we mean today by “evolution,” though. We use the term specifically to refer to the manner by which descendants come to differ from their biological ancestors. Dar-win called it “descent with modification.” There are, of course, chapter three Evolutionary Concepts 54 / Evolutionary Concepts many ways to theorize the relationship between descent and modification. They might be different processes, or different aspects of the same process. The modification might be brief in relation to the descent, or the descent might be brief in relation to the modification. There might be different roles for males and females, or there might be different kinds of responsiveness to the needs set by the environment for survival. adaptation For a notable example, take the fit between an organism and its environment, which we call “adaptation.” Aristotle believed it was the result of species simply having been built that way. Dar-win argued that it was rather the result of a long-term bias in survival and reproduction of organisms that differed slightly from the average, in the direction of a better fit. - No longer available |Learn more

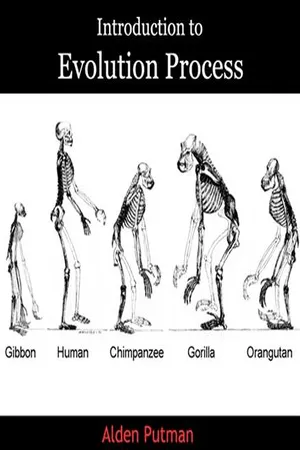

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- The English Press(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter- 1 Introduction to Evolution . Natural selection does not lead to perfection; dramatic changes in the environment often lead to mass extinctions, as in the case of the dinosaurs nearly 65 million years ago. Evolution is the process of change in all forms of life over generations and evolutionary biology is the study of how evolution occurs. The biodiversity of life evolves by means of natural selection, mutations and genetic drift. The process of natural selection is based on three conditions. First, every individual is supplied with hereditary material in the form of genes that are received from their parents then passed on to their offspring. Second, organisms tend to produce more offspring than the environment can support. Third, there are variations among offspring as a consequence of either the random introduction of new genes via mutations or reshuffling of existing genes during sexual reproduction. ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Natural selection will occur when these facts of nature (heredity, overproduction of offspring and variation) hold true. Natural selection means individuals do not have equal chances of reproductive success. As a consequence, some individuals produce more offspring and thus have a higher degree of fitness. Traits that ensure organisms are better adapted to their living conditions become more common in descendant populations. For this reason, populations will never remain exactly the same over successive generations. The forces of evolution are most evident when populations become isolated, either through geographic distance or by mechanisms that prevent genetic exchange. Over time, isolated populations can branch off into new species. Random genetic drift describes another natural process that regulates the evolution of minor mutations in the genes, leading to changes in allele frequencies over time. - eBook - PDF

- Samantha Fowler, Rebecca Roush, James Wise(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Openstax(Publisher)

11 | EVOLUTION AND ITS PROCESSES Figure 11.1 The diversity of life on Earth is the result of evolution, a continuous process that is still occurring. (credit “wolf”: modification of work by Gary Kramer, USFWS; credit “coral”: modification of work by William Harrigan, NOAA; credit “river”: modification of work by Vojtěch Dostál; credit “protozoa”: modification of work by Sharon Franklin, Stephen Ausmus, USDA ARS; credit “fish” modification of work by Christian Mehlführer; credit “mushroom”, “bee”: modification of work by Cory Zanker; credit “tree”: modification of work by Joseph Kranak) Chapter Outline 11.1: Discovering How Populations Change 11.2: Mechanisms of Evolution 11.3: Evidence of Evolution 11.4: Speciation 11.5: Common Misconceptions about Evolution Introduction All species of living organisms—from the bacteria on our skin, to the trees in our yards, to the birds outside—evolved at some point from a different species. Although it may seem that living things today stay much the same from generation to generation, that is not the case: evolution is ongoing. Evolution is the process through which the characteristics of species change and through which new species arise. The theory of evolution is the unifying theory of biology, meaning it is the framework within which biologists ask questions about the living world. Its power is that it provides direction for predictions about living things that are borne out in experiment after experiment. The Ukrainian-born American geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky famously wrote that “nothing makes sense in biology except in the light of evolution.” [1] He meant that the principle that all life has evolved 1. Theodosius Dobzhansky. “Biology, Molecular and Organismic.” American Zoologist 4, no. 4 (1964): 449. Chapter 11 | Evolution and Its Processes 249 and diversified from a common ancestor is the foundation from which we understand all other questions in biology. - eBook - PDF

Biodiversity in a Changing Climate

Linking Science and Management in Conservation

- Terry Louise Root, Kimberly R. Hall, Mark P. Herzog, Christine A. Howell, Terry Louise Root, Kimberly R. Hall, Mark P. Herzog, Christine A. Howell(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

Although humans can-not control evolution on a grand scale, we can take actions to protect and promote the evolu-tionary processes that create and maintain bio-diversity; that is to say, we can manage to maxi-mize adaptive genetic variation, which is the backbone of biological adaptation, and ulti-mately, biodiversity. We know that species are already respond-ing to the effects of human-caused climate change in several ways: Changing phenologies, shifting geographic ranges, and changing abundances (Root et al. 2003, Parmesan 2006, Anderegg and Root, this volume). Many of these shifts will be necessary for species to adjust to a rapidly changing climate, but may not always be fully realized due to constraints imposed by habitat availability and biological limits to migration and dispersal (Geber and Dawson 1993, Sexton et al. 2009). For those species that cannot move to suitable habitat, and have reached their limits of environmental tolerance, adaptation via evolutionary processes (see Rice and Emery 2003), or extinction, is the only option in the absence of human interven-tion (Ackerly 2003). Rapid evolution to changing conditions, including human-induced conditions, is not a new concept (Hendry et al. 2010). In the 19th century, Charles Darwin observed rapid evolu-tion in moths in response to industrial air pollu-tion. Agriculturalists use breeding and genetic technologies to increase yields under various growth environments by changing the traits of domesticated plants and animals. For example, modern-day corn is the product of human-induced evolution from thousands of years of domestication, with rapid evolution occurring during the last half-century through intensive evolutionary conservation under climate change 163 Invasive species give us clues as to how manage-ment can maximize evolutionary responses in native species (e.g. Griffith et al. 1989). - eBook - PDF

- Mary Ann Clark, Jung Choi, Matthew Douglas(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Openstax(Publisher)

We can attribute novel traits and behaviors to another evolutionary force—mutation. Mutation and other sources of variation among individuals, as well as the evolutionary forces that act upon them, alter populations and species. This combination of processes has led to the world of life we see today. Chapter 19 | The Evolution of Populations 517 19.1 | Population Evolution By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following: • Define population genetics and describe how scientists use population genetics in studying population evolution • Define the Hardy-Weinberg principle and discuss its importance People did not understand the mechanisms of inheritance, or genetics, at the time Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace were developing their idea of natural selection. This lack of knowledge was a stumbling block to understanding many aspects of evolution. The predominant (and incorrect) genetic theory of the time, blending inheritance, made it difficult to understand how natural selection might operate. Darwin and Wallace were unaware of the Austrian monk Gregor Mendel's 1866 publication "Experiments in Plant Hybridization", which came out not long after Darwin's book, On the Origin of Species. Scholars rediscovered Mendel’s work in the early twentieth century at which time geneticists were rapidly coming to an understanding of the basics of inheritance. Initially, the newly discovered particulate nature of genes made it difficult for biologists to understand how gradual evolution could occur. However, over the next few decades scientists integrated genetics and evolution in what became known as the modern synthesis—the coherent understanding of the relationship between natural selection and genetics that took shape by the 1940s. Generally, this concept is generally accepted today. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Learning Press(Publisher)

These investigations were prompted by the neutral theory of molecular evolution, which proposed that most Evolutionary Changes are the result of the fixation of neutral mutations that do not have any immediate effects on the fitness of an organism. Hence, in this model, most genetic changes in a population are the result of constant mutation pressure and genetic drift. This form of the neutral theory is now largely abandoned, since it does not seem to fit the genetic variation seen in nature. However, a more recent and better-supported version of this model is the nearly neutral theory, where most mutations only have small effects on fitness. Outcomes Evolution influences every aspect of the form and behaviour of organisms. Most prominent are the specific behavioural and physical adaptations that are the outcome of natural selection. These adaptations increase fitness by aiding activities such as finding food, avoiding predators or attracting mates. Organisms can also respond to selection by co-operating with each other, usually by aiding their relatives or engaging in mutually beneficial symbiosis. In the longer term, evolution produces new species through splitting ancestral populations of organisms into new groups that cannot or will not interbreed. These outcomes of evolution are sometimes divided into macroevolution, which is evolution that occurs at or above the level of species, such as extinction and speciation, and microevolution, which is smaller Evolutionary Changes, such as adaptations, within a species or population. In general, macroevolution is regarded as the outcome of long periods of microevolution. Thus, the distinction between micro- and macroevolution is not a fundamental one – the difference is simply the time involved. However, in macroevolution, the traits of the entire species may be important. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Academic Studio(Publisher)

A common misconception is that evolution has goals or long-term plans; realistically however, evolution has no long-term goal and does not necessarily produce greater complexity. Although complex species have evolved, they occur as a side effect of the overall number of organisms increasing, and simple forms of life still remain more common in the biosphere. For example, the overwhelming majority of species are microscopic prokaryotes, which form about half the world's biomass despite their small size, and constitute the vast majority of Earth's biodiversity. Simple organisms have therefore been the dominant form of life on Earth throughout its history and continue to be the main form of life up to the present day, with complex life only appearing more diverse because it is more noticeable. Indeed, the evolution of microorganisms is particularly important to modern evolutionary research, since their rapid reproduction ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ allows the study of experimental evolution and the observation of evolution and adaptation in real time. Adaptation Adaptation is one of the basic phenomena of biology, and is the process whereby an organism becomes better suited to its habitat. Also, the term adaptation may refer to a trait that is important for an organism's survival. For example, the adaptation of horses' teeth to the grinding of grass, or the ability of horses to run fast and escape predators. By using the term adaptation for the evolutionary process, and adaptive trait for the product (the bodily part or function), the two senses of the word may be distinguished. Adaptations are produced by natural selection. The following definitions are due to Theodosius Dobzhansky. 1. Adaptation is the evolutionary process whereby an organism becomes better able to live in its habitat or habitats. - eBook - PDF

- Stephen Jay Gould(Author)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Belknap Press(Publisher)

The natural selection of alternative alleles, acting largely independently at each locus, is the only force tending to maintain or improve adapta-tions shown by the ephemeral organisms formed by the ephemeral geno-types. If one could look back to the evolution of our own or any other sexually reproducing species, back to well before the Cambrian, no other fitness enhancing process of any importance would be found. Having taken that position, I must take another. The microevolutionary process that adequately describes evolution in a population is an utterly inade-quate account of the evolution of the earth’s biota. It is inadequate be-cause the evolution of the biota is more than the mutational origin and subsequent survival or extinction of genes in gene pools. Biotic evolution is also the cladogenetic origin and subsequent survival and extinction of gene pools in the biota. The Grand Analogy: A Speciational Basis for Macroevolution PRESENTATION OF THE CHART FOR MACROEVOLUTIONARY DISTINCTIVENESS When Niles Eldredge and I first formulated the theory of punctuated equilib-rium in the early 1970’s (Eldredge, 1971; Gould and Eldredge, 1971; Eldredge 714 THE STRUCTURE OF EVOLUTIONARY THEORY and Gould, 1972; Gould and Eldredge, 1977), we had only the germ of an insight that its tenets could lend support to a generalized theory of macro-evolution, then entirely undeveloped. We did, however, dimly grasp the key notion that punctuated equilibrium might help to grant species a sufficient stability and coherence for status as what we would now call an evolutionary individual, or unit of selection. We developed this insight by groping towards an analogy that, when generalized and fully fleshed out (with apologies for another parochial organismic metaphor of common language!), sets a foun-dation for macroevolutionary theory.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.