Biological Sciences

Filamentous Bacteria

Filamentous bacteria are a type of bacteria that have a long, thread-like shape, often forming chains or filaments. They are commonly found in various environments, including soil, water, and wastewater treatment systems. Filamentous bacteria play important roles in nutrient cycling and can have both beneficial and detrimental effects in different ecosystems.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

6 Key excerpts on "Filamentous Bacteria"

- eBook - ePub

- Iqbal Ahmad, Fohad Mabood Husain, Iqbal Ahmad, Fohad Mabood Husain(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Microbiologists have documented that microbial populations in their natural environments form biofilms—complex communities attached to surfaces in a self-produced polymeric matrix [3–6]. The study of microbial biofilms has led to a shift in our understanding of how microorganisms grow, survive, adapt, and exploit hosts and resources. The bulk of biofilm research has been done on bacteria in aquatic or clinical settings, and a few examples on plants [7–9]. Fungal biofilms have also been studied, mainly in model yeast pathogens responsible for human and animal diseases [10–14]. Only recently have reports of filamentous fungal biofilms been gradually accumulating. The focus of this chapter is to review and integrate what is known about filamentous fungal biofilms with special attention to those formed on or within plant tissues or in soils.8.2 What Is a Biofilm?

The linguistic meaning of the word biofilm literally translates to “biological material in a thin layer, ” but the more we learn about biofilms, the more difficult it is for all to agree on a single definition [15, 16]. A definition for filamentous biofilms becomes additionally challenging because of the unique morphology and tip growth of hyphal filaments when compared to the single-celled populations of bacteria or yeasts undergoing binary fission or budding. Filamentous fungi cannot always be cultured, measured, manipulated, or enumerated using the same experimental protocols as those used for the individual cells within bacteria and yeast biofilms. As a result, methods for describing and quantifying filamentous fungal biofilms are quite different from those established for bacteria and budding yeasts. Despite these challenges, it is important to define the term biofilm for the purposes of this chapter such that it is inclusive to bacteria, yeast, and filamentous microorganisms growing in natural environments or under laboratory conditions. Herein, we use biofilm - Per Halkjaer Nielsen, Holger Daims, Hilde Lemmer, Idil Arslan-Alaton, Tugba Olmez-Hanci(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- IWA Publishing(Publisher)

5 Identification of Filamentous Bacteria by FISH Caroline Kragelund, Elisabeth Mu ¨ller, Margit Schade, Hien Thi Thu Nguyen, Hilde Lemmer, Robert Seviour, and Per Halkjær Nielsen 5.1 INTRODUCTION Filamentous Bacteria are found in all types of WWTPs, where they are often responsible for bulking (e.g. inadequate separation of biosolids and liquid effluent phases) or foaming (biosolids transported to the surface of either process tank or clarifier, typically dominated by one or two filamentous morphotypes). Filamentous Bacteria should be considered as normal members of the activated sludge communities, primarily involved in degradation of organic material. Under some conditions they proliferate to such an extent that they markedly affect treatment plant performance. Their relative abundance may then exceed the usual 1–3% of the total biomass. The reasons for their excessive proliferation are many and will not be covered in this chapter, since several recent reviews and books discuss this in detail (Eikelboom, 2000; Jenkins et al ., 2004; Tandoi et al ., 2006; Nielsen et al. , 2009; Seviour et al. , 2009). In order to control the growth of these problematic bacteria, their reliable identification is necessary as the factors known to promote their growth can vary considerably. These include presence of sulphides in the influent, lack of nutrients or low oxygen concentrations in the process tank. Methods used for their attempted control are described elsewhere [for an overview on causes of sludge separation problems and control measures in several countries see (Tandoi et al ., 2006)]. Filamentous Bacteria also inhabit biofilm systems where they are located often at their surfaces (Galvan and de Castro, 2007). Here they rarely cause problems. Bulking arising from their excessive presence may occur, but only occasionally when clarifiers are employed to # 2009 IWA Publishing.- eBook - ePub

- Alexandru Grumezescu(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Husham et al., 2012 ). The purpose of this chapter is to present the characteristics of microbial biofilms found in the aquatic ecosystems with a special focus on their both negative and beneficial roles for the water treatment and quality.2. Definition of Biofilm

Biofilm represents a structured microbial community adherent to an inert or living surface embedded in a self-secreted polymeric matrix (Zarnea and Popescu, 2011 ). It has a heterogeneous structure, the cells embedded in this matrix exhibiting a modified phenotype, especially concerning the growth rate and gene transcription, and a mono- or, the most often, a multispecific composition, regulated by multiple signaling mechanisms dependent on the cellular density, known as quorum sensing and response (QS) systems (Costerton, 2009 ; Donlan, 2002 ; Lazãr and Chifiriuc, 2010a ). In QS, the communication between the cellular components of a biofilm is achieved by chemical signal micromolecules with different structures represented by peptides in Gram-positive bacteria and l -homoserin-lactones in Gram-negative species (Davey and O’Toole, 2000 ; Davies et al., 1993 ; 1998 ; Chifiriuc et al., 2014 ). The QS regulation mechanism is involved in various physiological processes (biofilm formation, antibiotic production, bioluminescence, genetic competence, sporulation, swarming motility), as well as in the expression of virulence potential (Lazãr and Chifiriuc, 2010b ). It has been shown that the QS-mutant strains have a decreased potential to develop mature biofilms, forming only thin and uniform structures (Delden and Iglewski, 1998 ). When the signaling molecules reach a threshold concentration which reflects a certain density of the microbial cells inside biofilm, the gene expression of 40–60% of the bacterial genome is changed having a consequence that the modification of biofilm cells phenotype in comparison with that of their planktonic counterparts (Israil and Chifiriuc, 2009 - (Author)

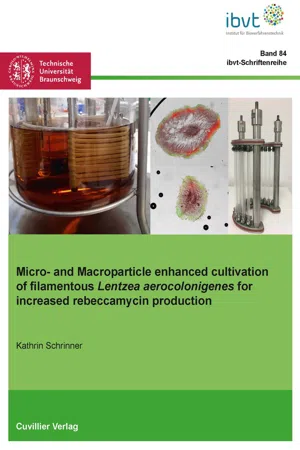

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Cuvillier Verlag(Publisher)

Es gilt nur für den persönlichen Gebrauch. Theoretical background 9 or pharmaceutical industry (Walisko et al. 2015). The bacterial filamentous Actinomycetes , including L. aerocolonigenes , are especially interesting because of the production of mainly pharmaceutically relevant secondary metabolites (Nielsen 1996; Kieser et al. 2000). In the year 2000 60 % of the known biologically active secondary metabolites were isolated from Actinomycetes (Kieser et al. 2000). Although there are clear differences between Filamentous Bacteria and fungi, their morphology and its influence during a cultivation process are similar (Olmos et al. 2013; Nielsen 1996). Figure 2.2: Morphologic diversity of the filamentous actinomycete Lentzea aerocolonigenes in different cultivations ranging from (a) single hyphae, over mostly mycelial structures (b – d) up to dense and defined pellets in various sizes (e – i). The different morphological forms of filamentous microorganisms can affect the cultivation process by influencing different parameters such as the viscosity of the cultivation broth and thus the mixing performance as well as the costs for downstream processing (Wucherpfennig et al. 2010). At high biomass concentrations mycelial structures or pellets with many freely exposed hyphae in their periphery can lead to a high viscosity with a non-Newtonian flow behavior (Wucherpfennig et al. 2010; Bliatsiou et al. 2020). In a highly viscous cultivation broth, the mass transfer and mixing performance are impeded. In order to ensure a sufficient nutrient and oxygen supply of the microorganism an increased power input is necessary (Oncu et al. 2007). A large power input in turn causes high mechanical stress and therefore 100 μ m 1000 μ m 2000 μ m 2000 μ m 2000 μ m 2000 μ m 2000 μ m 2000 μ m 2000 μ m a b c d e f g h i Dieses Werk ist copyrightgeschützt und darf in keiner Form vervielfältigt werden noch an Dritte weitergegeben werden. Es gilt nur für den persönlichen Gebrauch.- eBook - PDF

Activated Sludge

Bulking and Foaming Control

- Jiri Wanner(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

As a compromise, today they describe these microor-ganisms as LeucothrixAike filaments [123,124]. The term LeucothrixAike filaments is very broad and is used for all microorganisms resembling Eikelboom's Types 021N and possibly 0041. This pragmatic approach seems to be better, especially in doubtful cases, than to assign the microor-ganism to a species or to a type by force. Microscopic fungi (micromycetes) were summarized by Eikelboom into one type. In his original 1975 paper [17], he explained about fungi that no attempts have been made in the present study to classify these organisms as they were never found to be the dominating type of filamentous or-ganism As this statement is not always quite right (as it was not at that time, either), some space should be devoted to fungi. Some microbiolo-gists complain that the low frequency of occurrence of micromycetes re-ported in activated sludges is because people do not look for them in a microscope. (True, but microscopic fungi usually form structures not so easily overlooked by careful examiners). The presence of fungi in the biocenosis of activated sludge should not 186 FILAMENTOUS MICROORGANISMS IN ACTIVATED SLUDGE necessarily be detrimental to settling properties. Grabinska-Loniewska [125] described the formation of large and compact activated sludge floes on hyphae of Fusarium, which is one of the most common genus of hyphal fungi found in activated sludges. Cyrus and Sladka [53] observed the for-mation of activated sludge floes on the skeleton of branched mycelium of Saprochaete saccharophila, a microorganism which will be described later. When bulking by fungi occurs, Geotrichum candidum is, in most cases, the causative organism. This yeast-like organism produces extended dichotomously branching hyphae which can interfere with floe settling (bridging effect). Moreover, the mycelium of Geotrichum candidum has a tendency to float, which deteriorates the settling properties even more. - eBook - ePub

Microbial Biofilms

Properties and Applications in the Environment, Agriculture, and Medicine

- Bakrudeen Abdul, Bakrudeen Ali Ahmed Abdul, Bakrudeen Abdul, Bakrudeen Ali Ahmed Abdul(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Biofilm based wastewater treatment involves metabolic activities of biofilm dwelling microorganisms which play a major role in pollutant degradation. Biofilm is a strong and unique ecological niche harboring living as well as dead microorganisms including bacteria, protozoans, algae, and various other microflora. Biofilms are ubiquitous in natural environment such as water and soil, living tissues, medical devices (medical biofilms), and industrial and drinking water distribution systems (Chandki et al., 2011). Biofilms provide a wide range of advantages to its members such as protection and resistance against antimicrobial agents (drugs and disinfectants), harsh and stressful environmental conditions such as dehydration, lack of nutrients, and UV radiations (Santos et al 2018).In multispecies biofilm, the bacterial population has to compete for the nutrients to survive. However, in a multispecies biofilm, bacteria not only compete for required nutrients but also for their integration in the microbial communities. Hence, biofilm forming bacteria have to seek out for the environmental conditions and bacterial colonies that are suitable for existence as well as growth (Abu Khweek & Amer, 2018). Biofilms have distinct heterogeneous internal structure, i.e., comprise of clusters containing cells, excreted polymeric network, and pores filled with the liquid to occupy the free spaces between the clusters. Each cluster has layers containing diverse microbial species, varied polymer compositions, and different densities of active cells. In aerobic heterotrophic biofilms, filamentous structures “streamers” extend out of the film into the external liquid. Masses of cells extend from a thin basal biofilm attached to the solid surface. As the biofilms get older with time, their physical structure changes, and biopolymers form bridges between clusters and increase the cell density (Melo, 2003).The major component of biofilm architecture is the extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) also called slime. Microorganisms embedded within the EPS stick to each other and to the surface as well. Biofilms mainly consist of microbial cells and EPS. EPS might differ in physical and chemical properties, but it is mainly composed of polysaccharides, extracellular DNA, proteins, and lipids. In case of Gram-negative bacteria EPS is neutral or polyanionic. However, in case of some Gram-positive bacteria EPS may be cationic. Due to incorporation of a high amount of water by hydrogen bonding, EPS is very hydrated. There is a five-stage universal growth cycle of a biofilm with common characteristics independent of the phenotype of the organisms (Aparna and Yadav , 2008). The biofilm formation is usually confirmed by the presence of EPS. Staining is a widely used technique for the detection of biofilms (Tanaka et al., 2019). Various studies revealed that overproduction of EPS varies the colony morphology and can be used for the identification of certain species. The polysaccharide constituent of the matrix in the biofilm can provide many benefits to the cells like structure, protection, and adhesion. Aggregative polysaccharides adhere bacterial cells to each other as well as to surfaces. Adhesion promotes the colonization of living and nonliving surfaces by promoting the resistance in bacteria against physical stresses of fluid movement which can detach the cells from nutrient substrates. Polysaccharides can also give protection from different stresses like dehydration, immune effectors, phagocytic cells, and amoebae. Additionally, these compounds may provide definite structure to biofilms, classify the bacterial community, and separate nutrient gradient and waste products. This helps in establishing a heterogeneous population capable of withstanding stress created by the sudden changing environments that many bacteria may confront. The ubiquitous polysaccharide structures, properties, and functions aid in successful adaptation of bacteria to almost every niche (Limoli et al., 2015).

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.