Biological Sciences

Filamentous Fungi

Filamentous fungi are a group of fungi characterized by their thread-like structures called hyphae. These fungi play important roles in various ecosystems, including decomposition and nutrient cycling. They are also used in biotechnology for producing enzymes, antibiotics, and food products. Examples of filamentous fungi include molds and mildews.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Filamentous Fungi"

- eBook - PDF

- Gupta, Rajan Kumar(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Daya Publishing House(Publisher)

It has seen that key genes such as sulA and minCD has involved in filamentation in E. coli (Bi, and Lutkenhaus, 1993). Here we shall be review the effects of morphological changes of some micro-organism in biological process which has many applications in food or pharmaceutical industries and medical field. The Fungi Multi-cellular Fungi Filamentous Fungi are eukaryotic and multi-cellular organisms, used in industrial metabolites production ( i.e . in secreting enzymes or proteins, organic acid, antibiotics or low mol.wt sugars) due to their metabolic versatility and to their capability (Villena and Gutierrez-Correa, 2007). Biofilms are morphological structure of Filamentous Fungi and could form as a result of antibiotic-resistant mode of microbial life, found in natural and industrial settings. In industrial application, study of morphological patterns of biofilms of Filamentous Fungi such as Aspergillus niger ATCC 10864 is useful for analysis of differential physiological behaviour of the strain and it provides the information for enhancement of lignocellulolytic enzyme productivity in submerged cultures (SC). Hyphae elongation at 8 h of this strain could be seen in Figure 20.1 A and this hyphe elongation causes the biofilm formation at 72 h (Papagianni, 2004; Villena and Gutierrez-Correa, 2007). Fungal biofilms are morphological efficient systems for metabolites production and share favourable physiological aspects also (shown in Figure 20.1 B). The surface-associated communities of bacterial cells are encapsulated in an extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) matrix. Fungal morphology of A niger could be affected by spore inoculum level in fermentation of citric acid. - eBook - PDF

- Dilip K. Arora(Author)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

5 Genomics of Filamentous Fungi: A General Review Ahmad M.Fakhoury/Gary A.Payne North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina, USA 1 INTRODUCTION In recent years, we have witnessed a real revolution in the biological sciences with the advent of powerful technologies and applications. These new technologies have ushered biology into the “genomics era” where studies involving whole genomes are possible. In fact, the beauty of this technology is that it transcends the answering of old questions and challenges us to formulate and address even more complex biological questions. For example, the quality and the amount of data generated through the use of these techniques allow us to study not only the complex metabolic pathways in an individual, but through comparative genomics it also allows us to gain a better understanding of the evolution of development and metabolic pathways, and to determine the genetic relatedness among organisms. In the following pages we tried to cover, as much as possible, recent advances achieved in the field, with an emphasis on work related to Filamentous Fungi. Due to the vast amount of data generated in recent years and the extensive use of the techniques and approaches described, we tried to be as inclusive as possible in covering the most recent work published at the time this manuscript was prepared. 2 Filamentous Fungi Fungi are a diverse group of organisms belonging to the Kingdom Mycota. They have been used through history in a multitude of industrial applications, and recently as a source of valuable enzymes. In the Far East, members of the genera Aspergillus and Rhizopus are used to produce miso, soy sauce, and tempeh, and different species of the genus Penicillium are used to ripen cheese. Throughout the world, common yeast is used in brewing and in baking; whereas mushrooms are cultivated and considered as a delicacy in many countries. - eBook - PDF

Cellular Morphology

A novel Process Parameter for the Cultivation of Eukaryotic Cells

- (Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cuvillier Verlag(Publisher)

12 2 Theoretical Background 2.1 Cultivation of filamentous Mircoorganisms Due to their metabolic diversity, high production capacity, secretion efficiency, and capability of carrying out post-translational modifications, Filamentous Fungi are widely exploited as efficient cell-factories in the production of metabolites, bioactive substances and native or heterologous proteins, respectively. The commercial use of fungal microorganisms is reported for multiple sectors such as detergent industry, food and beverage industry, and pharmaceutical industry [9, 15-17]. However, one of the outstanding, and unfortunately, often problematic characteristics of Filamentous Fungi is their morphology, which is much more complex than that of unicellular bacteria and yeasts in submerged culture [13]. Depending on the desired product, the optimal morphology for a given bioprocess varies [18]. Optimal productivity correlates with a specific morphological form [14, 19, 20]. 2.1.1 Filamentous fungus Aspergillus niger and the model product fructofuranosidase The filamentous fungus Aspergillus niger, the black mold, belongs to the division Ascomycota, defined by the ascus (from the greek word “sac”), which is formed as microscopical sexual structure by spores by some of its members. The Ascomycota are the largest phylum of fungi, with over 64,000 species, which may be either single-celled (yeasts), filamentous (hyphal) or both (dimorphic) [21]. Most ascomycetes grow as mycelia and can form conidospores; they are able to reproduce in sexual and non-sexual form. Some molds, like A. niger, can only reproduce asexually, do not have a sexual cycle, and do not form asci [21]. For A. niger, asexual reproduction occurs through the dispersal of conidia, produced from fruiting bodies termed conidiophores, the morphology of which can vary extensively from species to species [21]. - eBook - ePub

- Iqbal Ahmad, Fohad Mabood Husain, Iqbal Ahmad, Fohad Mabood Husain(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Microbiologists have documented that microbial populations in their natural environments form biofilms—complex communities attached to surfaces in a self-produced polymeric matrix [3–6]. The study of microbial biofilms has led to a shift in our understanding of how microorganisms grow, survive, adapt, and exploit hosts and resources. The bulk of biofilm research has been done on bacteria in aquatic or clinical settings, and a few examples on plants [7–9]. Fungal biofilms have also been studied, mainly in model yeast pathogens responsible for human and animal diseases [10–14]. Only recently have reports of filamentous fungal biofilms been gradually accumulating. The focus of this chapter is to review and integrate what is known about filamentous fungal biofilms with special attention to those formed on or within plant tissues or in soils.8.2 What Is a Biofilm?

The linguistic meaning of the word biofilm literally translates to “biological material in a thin layer, ” but the more we learn about biofilms, the more difficult it is for all to agree on a single definition [15, 16]. A definition for filamentous biofilms becomes additionally challenging because of the unique morphology and tip growth of hyphal filaments when compared to the single-celled populations of bacteria or yeasts undergoing binary fission or budding. Filamentous Fungi cannot always be cultured, measured, manipulated, or enumerated using the same experimental protocols as those used for the individual cells within bacteria and yeast biofilms. As a result, methods for describing and quantifying filamentous fungal biofilms are quite different from those established for bacteria and budding yeasts. Despite these challenges, it is important to define the term biofilm for the purposes of this chapter such that it is inclusive to bacteria, yeast, and filamentous microorganisms growing in natural environments or under laboratory conditions. Herein, we use biofilm - eBook - ePub

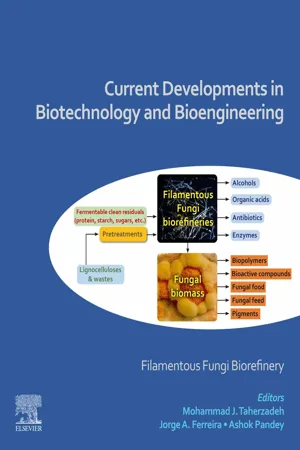

Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering

Filamentous Fungi Biorefinery

- Mohammad Taherzadeh, Jorge Ferreira, Ashok Pandey(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Elsevier(Publisher)

7: Filamentous fungal morphology in industrial aspects

Anil Kumar Patela , b ; Ruchi Agrawalc ; Cheng-Di Donga ; Chiu-Wen Chena ; Reeta Rani Singhaniaa ; Ashok Pandeyd , ea Department of Marine Environmental Engineering, National Kaohsiung University of Science and Technology, Kaohsiung City, Taiwanb Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, National Kaohsiung University of Science and Technology, Kaohsiung City, Taiwanc The Energy and Resources Institute, TERI Gram, Gwal Pahari, Haryana, Indiad Centre for Innovation and Translational Research, CSIR-Indian Institute of Toxicology Research, Lucknow, Indiae Sustainability Cluster, School of Engineering, University of Petroleum and Energy Studies, Dehradun, IndiaAbstract

High-production capacity, secretion efficiency, metabolic diversities, and capability to carry out posttranslational modifications enables Filamentous Fungi to be widely exploited as cell factories in the production of metabolites, bioactive substances as well as native and heterologous proteins. Industrial applications of Filamentous Fungi gave a big boost to bioproducts such as enzymes, antibiotics, organic acids, mycotoxins, etc. Filamentous Fungi have its intervention in almost all the industrial applications of bioproducts. Its morphology plays an extremely important role in industrial scale production of metabolites. Both the morphology, such as suspended or dispersed mycelia as well as pellet form have its own advantages and disadvantages. Scientifically, it is possible to control the morphology of fungi and exploit it according to the application. Several factors that affects its morphology have been discussed in this chapter which allows the process to be controlled. Genetic interventions have allowed to modify fungal strain according to our needs either to improve the production titer or to improve the properties of the product. In this chapter factors associated with fungal morphology as well as industrial applications of Filamentous Fungi have been discussed with emphasis on pulp and biofuel industry. - eBook - PDF

- (Author)

- 2001(Publication Date)

- Elsevier Science(Publisher)

Filamentous Fungi are such superior colonizers of soil that most terrestrial plants have recruited them as mycorrhizal partners (Smith and Read, 1997). Indeed, mycorrhizal fungi were already associated with the very first terrestrial plants some 400 million years ago (Simon et al., 1993; Remy et al., 1994). The ability of Filamentous Fungi to secrete vast quantities of extracellular enzymes, a direct consequence of the polarized organization of the hypha (Wessels, 1993), has also rendered these organisms useful tools for biotechnological purposes (Peberdy, 1994). A second fungal growth form is the yeast state, consisting of ellipsoid or near- spherical cells which multiply by budding or, rarely, fission. Yeasts are found where penetration of the substratum is not required, e.g. as saprotrophs on plant surfaces or in the digestive tracts of animals (do Carmo-Sousa, 1969; Carlile, 1995). Further, certain Filamentous Fungi are capable of switching between the hyphal and yeast states (Gow, 1995a). Such dimorphism is common in certain animal and plant diseases in which it may aid the dispersal of the pathogen. Yeast cells are viewed as insufficiently polarized hyphae (Wessels, 1993) and will be discussed in this context where appropriate. The hyphal growth form as the basis of nutrition by extracellular digestion has been used as a criterion to classify the fungi as a separate kingdom (Whittaker, 1969). Latterly, detailed genetic analyses have revealed this kingdom to be polyphyletic, resulting in the exclusion of the Oomycota and other groups (Alexopoulos et al., 1996). The occurrence of hyphae in several distinct evolutionary lineages may be seen as independent confirmation of the need of such structures for the associated mode of nutrition. - eBook - PDF

- Davis, Z(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Agri Horti Press(Publisher)

Introduction 1 1 Introduction The organisms of the fungal lineage include mushrooms, rusts, smuts, puffballs, truffles, morels, molds, and yeasts, as well as many less well-known organisms. More than 70,000 species of fungi have been described; however, some estimates of total numbers suggest that 1.5 million species may exist. As the sister group of animals and part of the eukaryotic crown group that radiated about a billion years ago, the fungi constitute an independent group equal in rank to that of plants and animals. They share with animals the ability to export hydrolytic enzymes that break down biopolymers, which can be absorbed for nutrition. Rather than requiring a stomach to accomplish digestion, fungi live in their own food supply and simply grow into new food as the local environment becomes nutrient depleted. Most biologists have seen dense filamentous fungal colonies growing on rich nutrient agar plates, but in nature the filaments can be much longer and the colonies less dense. When one of the filaments contacts a food supply, the entire colony mobilizes and reallocates resources to exploit the new food. Should all food become depleted, sporulation is triggered. Although the fungal filaments and spores are microscopic, the colony can be very large with individuals of some species rivaling the mass of the largest animals or plants. Prior to mating in sexual reproduction, individual fungi communicate with other individuals chemically via pheromones. In every phylum at least one pheromone has been characterized, and they range from sesquiterpines and derivatives of the carotenoid pathway in chytridiomycetes and zygomycetes to oligopeptides in ascomycetes and basidiomycetes. This ebook is exclusively for this university only. Cannot be resold/distributed. 2 Introduction to Fungi Fig . Hyphae of a Wood-decaying Fungus found Growing on the Underside of a Fallen log. The Metabolically Active Hyphae have Secreted Droplets on their Surfaces. - eBook - ePub

Applied Mycology for Agriculture and Foods

Industrial Applications

- Sanjay K. Singh, Deepak Kumar, Md. Shamim, Rohit Sharma, Sanjay K. Singh, Deepak Kumar, Md. Shamim, Rohit Sharma(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Apple Academic Press(Publisher)

Chapter 14 Role of Filamentous Fungi in the Production of Antibiotics or Antimicrobial AgentsHIMANKI DABRAL1 ,2, HEMANT R. KUSHWAHA3 , and ANU SINGH2 ,31 School of Agriculture Sciences, Shri Guru Ram Rai University, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India2 Samvet Bharat, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India3 School of Biotechnology, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India_________________ Applied Mycology for Agriculture and Foods: Industrial Applications. Sanjay K. Singh, Deepak Kumar, Md. Shamim, & Rohit Sharma (Eds.) © 2024 Apple Academic Press, Inc. Co-published with CRC Press (Taylor & Francis)Abstract

Filamentous Fungi are rich source of production of medicinal compounds at the industrial level as high levels of proteins and metabolites secreted by fungi in their culture medium possess efficient biomedical properties. Fungal species generally possess specific biomedical activities, however, out of a total 1.5 million only ~1,800 fungal species are described to have biomedical activities and prospects to explore new compounds for new biomedical and industrial applications. Initially, Filamentous Fungi (e.g., Trichoderma, Aspergillus, Rhizopus, and Penicillium species) were explored for their extraordinary extracellular enzyme synthesis mechanisms and protein secretion machinery for producing single cell proteins for large scale industrial production. Recent developments in the fields of genomics and proteomics offers new opportunities to biotechnologists to combine all the information to extend the bio-manufacturing of recombinant proteins of fungal origins in Filamentous Fungi. This can be achieved by facilitating Filamentous Fungi to express multiple proteins encoding genes and identifying new biosynthetic pathways to produce new proteins as well as secondary metabolites. Similarly, bacterial cells are also used as bio-factory to express proteins of fungal origin, this method reduces the time of production as compared to fungal method. - eBook - PDF

Fermented Foods, Part I

Biochemistry and Biotechnology

- Didier Montet, Ramesh C. Ray, Didier Montet, Ramesh C. Ray(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Filamentous Fungi in Fermented Foods Eta Ashu, 1,# Adrian Forsythe, 1,# Aaron A. Vogan 1,# and Jianping Xu * 1. Introduction Fermentation has long been used by humans for preserving food and for enhancing the nutritional and gastronomical values of foods. Broadly defined, fermentation refers to any form of food processing that involves the conversion of carbohydrates to alcohols and carbon dioxide or to organic acids using fungi, bacteria, or a combination thereof, under anaerobic conditions. One of the best-known fermentations in contemporary culture is the chemical conversion of sugars into ethanol by unicellular fungi to produce alcoholic beverages such as wine, beer, and cider (Chapter 2 in this book). While Filamentous Fungi are known to play very important roles in medicine (e.g., for producing antibiotics), industry (e.g., for producing enzymes), agriculture (as edible mushrooms), and forestry (ectomycorrhizal fungi), their roles in food fermentation is far less appreciated. In this chapter, we provide an overview of the diversity of Filamentous Fungi as well as their roles in representative fermented foods from broad regions of the world. The major sections are divided according to the types (genus) of Filamentous Fungi. Within each genus, we describe the major fermented foods that the specific fungi are found in, including their roles in the fermentation processes. The problems and potential opportunities for future research are discussed. # These three authors contributed equally to the work. 1 Department of Biology, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4K1, Canada. E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] * Corresponding author: [email protected] 3 46 Fermented Foods—Part I: Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2. Aspergillus In this section, we first introduce the fungal genus Aspergillus , including its general and diagnostic characteristics and the main species within this genus found in fermented foods. - eBook - PDF

Handbook of Soil Sciences

Properties and Processes, Second Edition

- Pan Ming Huang, Yuncong Li, Malcolm E. Sumner, Pan Ming Huang, Yuncong Li, Malcolm E. Sumner(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

These data suggest that mixotro-phic plants that live in forests derive photosynthates by sharing symbiotic fungi (Selosse and Roy, 2009). 24.4.3 Diversity in Mycorrhizal Features: Mycorrhizal Fungi Develop Structures Outside and Inside the Roots According to their ability to colonize the root cells, mycorrhizal fungi are divided into two main categories: endo- and ectomy-corrhizae. Since a detailed structural description of mycorrhizae is not the main aim of this chapter, we here only briefly review the main structural features that characterize mycorrhizal mor-phologies. More detailed information can be found in Peterson et al. (2004). Endomycorrhizal hyphae adopt a variety of colo-nization patterns during their penetration of host root cells. AM fungi depend on their hosts on a great extent and cannot survive for long without them. Once the fungus has overcome the epidermal layer, it develops an appressoria and grows inter- and intracellularly all along the root in order to spread fungal structures. During the symbiotic phase, some Glomeromycota (i.e., Glomus species) develop structures, called vesicles, that fill the cellular spaces, and probably act as storage pools. Only when the fungus has reached the cortical layers, does a peculiar branching process start, which leads to highly branched arbus-cules (Bonfante et al., 2009; Bonfante and Genre, 2010). These are the key structures that are produced during the symbioses, and are considered the site of nutrient exchange (Figure 24.8a). During endosymbiosis, regardless of the involved partners, a new apoplastic space, based on membrane proliferation, is built around all the intracellular hyphae (Bonfante, 2001). In AM, this new compartment is known as the interfacial compartment, and it consists of the invaginated membrane, the cell wall-like material, and the fungal wall, and plasma membrane (Balestrini and Bonfante, 2005). - eBook - ePub

- Manuel Simoes, Anabel Borges, Lucia Chaves Simoes(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Chapter 5The role of Filamentous Fungi in drinking water biofilm formation

Ana F.A. Chaves1, Lúcia Chaves Simões2,3, Russell Paterson2, Manuel Simões3, and Nelson Lima21 Faculty of Engineering, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal2 Centre of Biological Engineering, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal3 LEPABE — Laboratory for Process Engineering Environment, Biotechnology and Energy, Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University of Porto, Porto, PortugalAbstract

The presence of biofilms in drinking water distribution system (DWDS) constitutes one of the currently recognized hazards affecting the microbiological quality of drinking water (DW). Also, biofilms can alter the taste, odor, and the visual appearance of water, which is an indication of poor DW quality and may lead to a number of unwanted effects on the quality of the distributed water. Very few reports on Filamentous Fungi (ff) biofilms can be found in the literature mainly because these fungi do not conform completely to the biofilm definitions that are usually proposed for bacteria. Nevertheless, Filamentous Fungi are microorganisms that due to their (1) absorptive nutrition mode, (2) secretion of extracellular enzymes to digest complex molecules, and (3) apical hyphal growth that form lattices, which are excellent candidates for biofilm formation. However, this aspect is still poorly understood. In several environments, bacteria and ff cohabit and interact with each other, which has a wide range of applications and influences both organisms, sometimes creating an increase in resistance to antibiotics and antifungal agents. This chapter provides an overview on the presence of ff in DWDS, including their interaction with bacteria and potential biofilm formation.Keywords

Bacteria; Biofilms; Disinfection; Drinking water; Filamentous Fungi; Interactions5.1. Drinking water concerns

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.