Biological Sciences

Photoperiodism

Photoperiodism is the response of an organism to the length of day and night. It influences various biological processes such as flowering in plants, migration in birds, and reproduction in mammals. Photoperiodism is regulated by the perception of light and dark periods, which triggers specific physiological and behavioral changes in different species.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Photoperiodism"

- eBook - PDF

- Stanley D. Beck(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Chapter L Introduction to Photoperiodism From its earliest molecular origins life on earth has evolved in the presence of a daily cycle of daylight and darkness. This environmental rhythm of recurring alternation of illumination and darkness is the earth's natural photoperiod. Photoperiod has played an extremely important role in biological history; virtually every major group of eukaryotic organisms has evolved the ability to utilize the daily cycle and seasonal progressions of daylength as sources of environmental information. The geographical distribution, seasonal biology, growth, form, metabolism, and behavior of animal organisms are profoundly influenced by the diel rhythm of photoperiod. The effects of photoperiod on the organisms have to do not only with bioclimatic adaptations, but also with the temporal organization of the internal processes that characterize the living sys-tem. The diverse ways in which organisms are influenced by photoperiod are the subject matter of the biological field known as Photoperiodism. Biological phenomena such as photosynthesis and phototaxis are reactions to light energy and cease immediately on a cessation of illumination. A day-to-day rhythmicity is apparent in such reactions, because the environmental photoperiod provides a rhythmic input of light energy. The nocturnal or diurnal habits of some animals could conceivably involve only such direct responses to the pres-ence or absence of light energy. Photoperiodism has been found to involve much more than this, however. In nearly all cases, photoperiodic responses of insects and other animals have been shown to be based on the effects of the environmen-tal photoperiodic rhythm on internal biological rhythmic processes. It is appar-ent, therefore, that Photoperiodism is primarily an aspect of the more general subject of biological periodism, and only secondarily the responses of organisms to photostimuli per se. - eBook - PDF

- Mohammad Pessarakli(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

121 4 Photoperiodic Control of Flowering in Plants Faqiang Wu and Yoshie Hanzawa 4.1 INTRODUCTION Photoperiod, the daily cycle of day and night, is one of the most fundamental environmental signals for living organisms. Photoperiods regulate numerous biological events across all life forms, includ-ing cell division in yeast, diapause of insects, and coat color and sexual behavior of birds and animals (Classen et al. 1991, Danilevskii 1965, Eppley et al. 1967, Hoffmann 1973). In humans, dis-ruptions of the photoperiod cycles result in metabolic and psychological disorders. Photoperiodism, a word derived from the Greek words for “light” and “duration of time,” refers to the developmental and physiological reactions of organisms to the length of day and night, enabling them to adapt to seasonal changes in their environment. Photoperiodism thus may imply the ability and the means of organisms not only to recognize but also to memorize and anticipate seasonal changes in the length of day and night. Such mechanisms are especially important for organisms in the temperate zones, where a “clock” mechanism controlling seasonal developmental and physiological alterna-tives apparently measures the length of day and night (Saunders 2002). The mechanisms of photo-periodism are studied particularly well in plants. Photoperiodism involves various aspects of plant CONTENTS 4.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 121 4.2 Photoperiodic Flowering Research in the Premolecular Era ............................................... 122 4.2.1 Photoperiodism in Plants .......................................................................................... 122 4.2.2 Photoperiodic Time Measurement ............................................................................ 122 4.2.2.1 Plants Measure the Duration of Darkness ................................................. - eBook - PDF

- Klaus H. Hoffmann(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Physiological Cascades and the Molecular Basis of Photoperiodism The photoperiodic response in an organism comprises a sequence of several events (Fig. 4, Saunders 2002): (i) photoreception; (ii) assessment of day or night length by a photoperiodic time measurement system; Figure 4. Establishment of Photoperiodism through various modules. Light/dark signals are received by photoreceptors for Photoperiodism and for the circadian clock, which may or may not be identical depending on the species. The photoperiodic time measurement system measures the length of day or night and involves the circadian clock, while the counter system counts the number of photoperiodic cycles; together, these constitute the photoperiodic clock. When the number of cycles exceeds an internal threshold, the release/ restraint of endocrine effectors is triggered, inducing seasonal events. 222 Insect Molecular Biology and Ecology (iii) simultaneous evaluation of the number of photoperiodic cycles by a counter system; and (iv) activation of endocrine effectors that initiate the seasonal event. In this section, each physiological system and the associated molecular mechanism will be discussed in turn. Photoreceptors Visual retinal or nonvisual extraretinal photoreceptors allow organisms to detect photoperiodic information from the environment. Photoperiodic photoreceptors have been described in more than a dozen species from five different orders (Goto et al. 2010). For example, in the blowfly Protophormia terraenovae (Robineau-Desvoidy), photoperiodic induction of adult diapause was lost after the surgical removal of their compound eyes (Shiga and Numata 1997), underscoring the importance of retinal photoreceptors for initiating this physiological process. - eBook - ePub

Handbook of Agricultural Productivity

Volume II: Animal Productivity

- Miloslav Rechcigl(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Photoperiodism and Productivity of Domesticated Animals Robert K. RingerOrcadian and Circennial Rhythm

Biological observations over time have made scientists acutely aware of periodic functions in many animals. These observations suggest the intervention of some agencies that tend to adjust these periodic functions, which vary in frequency from cycles per minute to that of about one cycle/year. These cycles, of which there are many, are continually present within an animal.Of importance in a discussion of photoperiodic influence on animal productivity are two such biological rhythms: (1) circadian rhythms, with a frequency of more than 20- but less than 28-hr and (2) circa-annual or circennian rhythms, with a period of about 1 year.Circadian rhythms are inherited.’ Within limits, these endogenous biological clocks can be changed by external stimuli such as the dark-light photoperiod. If the stimuli are out of phase with the animal’s endogenous biological clock, a shift in the animal’s cycle must occur in order for the two cycles to become in phase. A shift may be a delay or an advance. An example of this endogenous biological clock synchronization with photoperiodic control and its relationship to animal productivity will be discussed later.Synchronization of Biological Rhythms

Light, by virtue of its daily and seasonal variations, is one of the principal synchronizing agents or cues for many species. It furnishes a reliable clock for diurnal rhythms and a calendar by which the animal schedules reproductive functions, metabolic adjustments, molts, and migrations that are compatible with other environmental alterations. These latter adjustments have been of adaptive significance and, in the case of reproduction, ensure that the young are born at the most propitious time for survival.Marshall2 - eBook - ePub

- H. Smith(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Butterworth-Heinemann(Publisher)

V Photoperiodism, Endogenous Rhythms and Phytochrome OutlineChapter 22: PHYTOCHROME AND Photoperiodism Chapter 23: Photoperiodism IN LIVERWORTS Chapter 24: LIGHT/TIMER INTERACTIONS IN Photoperiodism AND CARBON DIOXIDE OUTPUT PATTERNS: TOWARDS A REAL-TIME ANALYSIS OF Photoperiodism Chapter 25: PHYTOCHROME AND PHASE SETTING OF ENDOGENOUS RHYTHMS Chapter 26: THE NATURE OF PHOTOPERIODIC TIME MEASUREMENT: ENERGY TRANSDUCTION AND PHYTOCHROME ACTION IN SEEDLINGS OF CHENOPODIUM RUBRUMPassage contains an image 22

PHYTOCHROME AND Photoperiodism

DAPHNE VINCE-PRUE, Department of Botany, Plant Science Laboratories, University of Reading, Reading, U.K.Publisher Summary

Photoperiodic responses of many different kinds are seen in plants and animals from a variety of taxonomic groups and it may be that the formal similarities that occur among organisms that utilize the length of day and/or night as a signal for the time of year are merely reflections of a convergent evolution, which obscure significant differences in underlying mechanisms A photoperiodic response requires the ability to distinguish between light and darkness. In plants, the evidence points to phytochrome being the major and probably the only photoreceptor, but its precise role is unknown. The phenomenon of Photoperiodism implies that in some sense the organism measures time and it is the involvement with time measurement that complicates the analysis of phytochrome control of photoperiodic responses. This chapter describes some experiments concerning effects of phytochrome in photoperiodic responses. An important fact about the photoperiodic mechanism is that it operates only in de-etiolated plants, and dark-grown plants do not appear to show photoperiodic responses. The chapter also discusses the action of phytochrome in Photoperiodism. - Gupta, V K(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Daya Publishing House(Publisher)

According to this definition, Photoperiodism affects the long lasting events and it is based on the timing of light, thus darkness, and not on the amount of light or darkness (Kumar, 1997). Since the pioneer discovery of Rowan in 1925, the role of day length in control of seasonal reproduction and premigratory fattening has been confirmed in many high-, mid-, and low-latitude avian species. As the photoperiod is entirely predictable at given latitude, both within and between years, it is used as a fundamental cue to time the physiological preparations for the three major life-history stages: breeding, molt and migration in birds (Dawson, 2008). Almost all organisms, which have been investigated, are light sensitive. And in many organisms, especially those living away from the equator, the annual solar cycle has been found influencing various seasonal functions This ebook is exclusively for this university only. Cannot be resold/distributed. (Murton and Westwood, 1977; Thapliyal, 1981; Hoffman, 1981). At the equator where changes in daily light are small, the changes in daytime light intensity across seasons can influence seasonal responses (Gwinner and Scheuerlein, 1998). Among vertebrates, birds exhibit pronounced seasonal cycles in various behavioral and physiological functions, and several of them are influenced by annual changes in day length. Birds were the first vertebrates in which role of day length (= photoperiod) was demonstrated in control of seasonal functions. That the photoperiod (= day length) could act as a temporal information dates back to eighteenth century when Dutch netters realized that the song associated with breeding activity could be induced in males of several species of passerine birds by keeping them first in darkness from May to August and then returning to natural day lengths. However, nearly for two hundred years there was no scientific investigation.- eBook - PDF

- John Palmer(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

/. Agric. Res. 18, 553-607. Lees, A. D. (1971). The role of circadian rhythmicity in photoperiodic induction in an-imals. In Circadian Rhythmicity, pp. 87-110. Centre for Agricultural Publishing and Documentation, Wageningen, Netherlands. Menaker, M., ed. (1971). Biochronometry. Nat. Acad. Sei., Washington, D.C. Palmer, J. D. (1971). The rhythm of the flowers. Nat. Hist. 80, 64-73. Pengelley, E. T., ed. (1975). Circannual Clocks. Academic Press, New York. Salisbury, F. B. (1963). The Flowering Process. Macmillan, New York. Saunders, D. S. (1973). Circadian rhythms and Photoperiodism in insects. In The Phys-iology of Insecta (M. Rockstein, ed.), 2nd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 461-533. Academic Press, New York. Sweeney, Β. M. (1969). Rhythmic Phenomena in Plants. Academic Press, New York. Withrow, R. B., ed. (1959). Photoperiodism and Related Phenomena in Plants and An-imals, Publ. No. 55. Am. Assoc. Adv. Sei., Washington, D.C. this is used to support the hypothesis that the same clock that governs all other physiological rhythms is used in Photoperiodism also. 4. Not all photoperiodic responses in insects are governed by an escapement-type clock. A clock similar in action to an hourglass is used by some. 5. Seasonality in birds can be produced by a bioclock measure-ment of night lengths and by annual bioclocks. Other mechanisms are also used by birds, but these are outside the subject matter of this text. - eBook - PDF

- Brian Thomas, Daphne Vince-Prue(Authors)

- 1996(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

9 Some rhythms are reohased raoidlv (within one cycle in Gonvaulax), while others CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS AND PHOTOPERIODIC RESPONSES 37 may show transients before rephasing is complete (Johnson and Hastings, 1989). The rhythm is said to be reset when the new phase has been established. 9 Some rhythms damp quickly, while others persist for several cycles in a constant environment. 9 When rhythms persist in continuous light, the characteristics of the rhythm (period and PRC) may vary with the colour and/or intensity of the background illumination. 9 In several cases, the rhythm appears to damp, or be suspended, at a particular circadian time in continuous bright light; it then restarts at this circadian time following transfer to darkness, or dim light. Rhythms which continue in bright light may also be reset on transfer to darkness. 9 In some systems, a light treatment given at the appropriate phase of the rhythm apparently abolishes its subsequent expression (Lumsden and Furuya, 1986). All of these points should be borne in mind when considering how circadian rhythms may operate in photoperiodic timekeeping. CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS AND PHOTOPERIODIC RESPONSES Night-Break Experiments It is evident from the results of many experiments that Photoperiodism involves a rhythmic change of sensitivity to light. The most direct approach has been to combine a short photoperiod with a very long dark period and to scan the latter with a night- break of the kind known to modify the flowering response (see Chapter 1). Under these conditions, maximum inhibition (SDP) or promotion (LDP) of flowering has been observed to occur at circadian (i.e. approximately 24 h) intervals. Results with Lolium, Sinapis and Glycine are shown in Fig. 2.6 and it is evident that the peaks of promotion of flowering in the two LDP approximately coincide with the peaks of inhibition of flowering in the SDP Glycine. There is clearly a difference between LDP and SDP in the timing of their responses to light. - Ruth Porter, Geralyn M. Collins, Ruth Porter, Geralyn M. Collins(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

In: Aschoff J (ed) Handbook of behavioral neurobiology, vol 4: biological rhythms. Plenum, New York, p 95-124 Pittendrigh CS, Minis DH 1964 The entrainment of circadian oscillations by light and their role as photoperiod clocks. Am Nat 98:261-294 Pittendrigh CS, Minis DH 1971The photoperiodic time-measurement in Pectinophoru gossypiellu and its relation to the circadian system in that species. In: Menaker M (ed) Biochronometry. National Academy of Sciences, Washington DC, p 212-250 Physiol 17:450-457 Saunders DS 1976 Insect clocks, 1st edn. Pergamon Press, London CIRCADIAN COMPONENT IN PHOTOPERIODIC INDUCTION 41 Takahashi J, Menaker M 1982 Entrainment of the circadian system of the house sparrow: a population of oscillators in pinealectomized birds. J Comp Physiol 146:245-253 Tamarkin L, Westrom WK, Hamill AI, Goldman BD 1976 Effect of melatonin on the reproductive systems of male and female hamsters: a diurnal rhythm in sensitivity to melatonin. Endocrinology 99:1534-1541 Tyshchenko VP 1966 Two-oscillatory model of the physiological mechanism of insect photo- periodic reaction. Zh Obshch Biol 33:21-31 Vaz Nunes M, Veerman A 1982 External coincidence and photoperiodic time measurement in the spider mite Tefrunychus urficue. J Insect Physiol28:143-154 DISCUSSION Hodkova: In many insects-for example, adults of Pyrrhocoris apterus (Hodek 1971), adults of Psylla pyricola (McMullen & Jong 1976), and mature larvae of Molophilus uter (Coulson et a1 1976)-the photoperiodic response is lost with the completion of diapause development. Do you think that, for example, periods of oscillations may be changed during diapause develop- ment? Perhaps the photoperiodic entrainment of the post-diapause oscillations by any photoperiod results in the phase relationships, which do not allow diapause . Pittendrigh: That is one of several possible explanations but I have no particular preference for it.- eBook - ePub

- R. J. Collier, J. L. Collier, R. J. Collier, J. L. Collier(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Chapter 13 Effects of Photoperiod on Domestic Animals Geoffrey E. Dahl and Izabella M. Thompson IntroductionPhotoperiod is defined as the alternating exposure to light and dark on a daily basis. Lighted periods are termed the photophase, whereas darkness is the scotophase. Physiologically, the pattern of light exposure, particularly the relative duration of light and dark, affects a number of endocrine pathways to culminate in daily, monthly, and annual shifts in functions related to growth, reproduction, pelage, and immune function. From an evolutionary perspective, adoption of photoperiod as an ultimate driver for annual changes in physiological function is predictable because it is the most consistent environmental signal over extended periods of time (Gwinner, 1986). But photoperiod can also be harnessed to improve production in all farmed domestic species, especially in today's intensive systems.LightOne of the most frequent questions with regard to photoperiod concerns the relative difference between light and dark. Put another way, how dark is “dark” and how much light registers as a signal? Light intensity is measured and reported in footcandles (FC; English) or lux (Lx; metric), with a conversion ratio between the two of about 10 lux to 1 footcandle. Although there are limited data on domestic species in regard to the minimal intensity of light that is perceived as “light,” an illumination as low as 5 footcandles registers as light. This does not mean, however, that an intensity of less than 5 FC is “dark,” as animals may acclimate to lower intensities over time. In fact chickens can respond to intensities as low as 1 FC. The American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers (ASABE) recommends that all housing for domestic animals achieve an intensity of 15 footcandles or more. The maximum intensity measured under natural conditions exceeds 1,000 FC on a sunny day and even a cloudy day will routinely provide an intensity of 200 to 300 FC. Thus it is clear that animals have a wide, dynamic range of light perception, and the only true measure of darkness appears to be the absence of light. - C.-S. Lee, E.M. Donaldson(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Elsevier Science(Publisher)

1999) who transferred fish from ambient daylength to continuous light, LD 18:6 or LD 6:18 at regular intervals throughout the year. Spawning occurred over a number of months in all three experimental groups of fish.5 Endogenous biological clocks or rhythms

From the foregoing discussion of the relative importance of photoperiodic history and critical daylength in the timing of fish reproduction, it is clear that the response to seasonal changes in daylength, exhibited by many fish, cannot be accommodated within classical concepts of Photoperiodism as exemplified by many birds and mammals (Follett, 1984 ). A particular difficulty is the ability of fish to continue to spawn at approximately annual intervals under constant conditions of light, temperature, food, etc. (i.e. in the absence of any obvious changes in environmental cue). This has lead to suggestions that endogenous timing mechanisms may be in operation (Whitehead et al., 1978 ; Sundararaj et al., 1982 ; Bromage and Duston, 1986 ) and, because they relate to annual rhythms, they have been described as circannual (see Gwinner, 1986 ).Full acceptance of a rhythm as circannual depends on a number of criteria being met: firstly, the rhythm must be represented over more than one and preferably several cycles; secondly, under constant conditions it should “free-run” with a periodicity which approximates to, but is significantly different from a year; thirdly, it should be entrainable by environmental factors or cues; fourthly, the rhythm should not be unduly influenced by variations in temperature; and lastly, the rhythm should exhibit a differential response to photoperiod; this is dependent on the phase of the rhythm which is exposed to the photoperiod cue, i.e. it should display a phase response curve. Many of the earlier studies on fish do not satisfy all of these criteria, generally because they had only considered data from a single reproductive cycle or that all conditions had not been maintained at constant levels throughout the experiments (see Bromage and Duston, 1986 ; Duston and Bromage, 1986 , 1987 , 1988 , 1991 for further discussion). Amongst the earlier studies, only Sundararaj et al. (1982) working with the Indian catfish (Heteropneustes fossilis ) provided good evidence of a self-sustaining circannual rhythm, although such a rhythm was also proposed for the stickleback (Baggerman, 1980- eBook - PDF

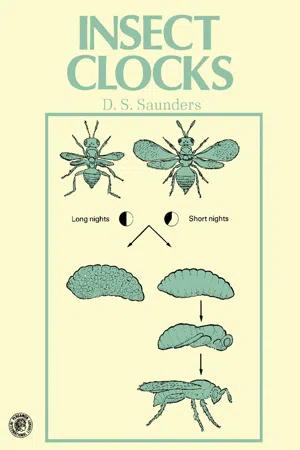

Insect Clocks

Pergamon International Library of Science, Technology, Engineering and Social Studies

- D. S. Saunders(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Pergamon(Publisher)

(After Beck, 1962.) Figures on the curves indicate temperatures in °C. 6 12 18 Photoperiod, hours FIG. 6.2. A long-day photoperiodic response curve showing its properties (schematic). The solid vertical lines indicate the range of natural photoperiods at 55°N. Regions a and d are therefore never experienced in nature. Region b only occurs during the winter when the temperature is probably below the minimum for development (and the insect is in dia-pause). Only region c is of ecological importance; note that this region is dominated by the critical daylength which operates the seasonal switch in metabolism. THE PHOTOPERIODIC RESPONSE 89 Photoperiodic response curves may differ in a number of ways. In some species, such as Leptinotarsa decemlineata, the response in DD is the same (about 100 per cent dia-pause) as in strong short daylengths (de Wilde, 1958). In others, such as Pectinophora gossypiella (Pittendrigh and Minis, 1971), Ostrinia nubilalis (Beck and Hanec, 1960), Pieris brassicae (Danilevskii, 1965) and Sarcophaga argywstoma (Saunders, 1971), the proportion entering diapause falls off in ultrashort daylengths. In conditions of constant darkness the response may vary from zero as in P. brassicae to 100 per cent as in L. decemlineata. It usually varies widely with temperature. In P. gossypiella the proportion entering diapause is apparently greater in DD than in photoperiods of 2 to 6 hours (Pittendrigh and Minis, 1971). Similarly, in very long photoperiods and in LL, the inci-dence of diapause may be higher than in natural long daylengths and, once again, be more variable than at points just longer than the critical (Williams and Adkisson, 1964; Pittendrigh and Minis, 1971). These unstable responses at the extremes presumably reflect the absence of any selective pressure.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.