Psychology

Circadian, Infradian and Ultradian Rhythms

Circadian rhythms are biological cycles that occur approximately every 24 hours, influencing sleep-wake patterns and hormone release. Infradian rhythms have a longer cycle, such as the menstrual cycle in humans. Ultradian rhythms are shorter cycles, like the stages of sleep or fluctuations in body temperature throughout the day. These rhythms play a crucial role in regulating various physiological and behavioral processes.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Circadian, Infradian and Ultradian Rhythms"

- eBook - PDF

State and Trait

State and Trait

- A. R. Smith, D. M. Jones(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

The pervasive nature of such rhythmic components in physiology and behaviour suggests that this circadian (from the Latin circa about, dies day; Halberg, 1959) temporal organization is vital to the overall well-being of the organism. Among the numerous systems and functions mediated by the circadian timing system are hormonal output, body core temperature, rest and activity, sleep and wakefulness, and motor and cognitive performance. In all, literally hundreds of circadian rhythms in mammalian species have been identified (see, for example, Aschoff, 1981; Conroy and Mills, 1970), and Aschoff (1965) has noted that 'there is apparently no organ and no function in the body which does not exhibit a similar daily rhythmicity'. Because of the predominance of rhythms recurring about once a day, biological rhythms with longer or shorter frequencies have typically been classified as infradian, or ultradian rhythms, respectively. An example of an infradian rhythm is the human menstrual cycle. An example of an ultradian rhythm is the recurrence of dream sleep (REM sleep) about every ninety minutes throughout a normal night's sleep. It is rhythms in the circadian range, and to a lesser extent the ultradian range, that are of primary relevance Effects of Sleep and Orcadian Rhythms on Performance 197 to this chapter. Most performance measures show oscillations in the twenty-four hour range, though considerable evidence suggests shorter-term fluctuations, as well. Likewise, the human sleep/wake cycle, which so profoundly influences performance, is primarily a circadian system, but with important ultradian components. Sleep as a biological rhythm In the early 1960s, Aschoff and co-workers began studies which, over the next twenty years, would lay the foundation for much of what we know today about the human circadian system (for a summary of much of this work, see Aschoff and Wever, 1 9 8 1 ; Wever, 1979). - eBook - PDF

- Roberto Refinetti PhD.(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Further research is necessary to determine whether there is a specific ultradian pacemaker responsible for the oscillations shorter than 5 hours. A possible alternative is that the oscillations are generated by frequency modulation of other ultradian oscilla-tors, such as the one responsible for GnRH pulses. An addi-tional possibility is that the ultradian oscillations result from the operation of an hourglass mechanism associated with the time constant of the sleep homeostat, 126 as will be discussed in Chapter 10. 4.3 INFRADIAN RHYTHMS In contrast to ultradian rhythms, infradian rhythms are bio-logical processes that cycle with a frequency lower than that of circadian rhythms—which means that their period is lon-ger than that of circadian rhythms. Infradian rhythms include the reproductive cycles of female animals ( estrous cycle ), the organization of human activities into weeks ( weekly rhythms ), and the monthly alteration of physiological processes associ-ated with the lunar cycle ( lunar rhythms ). Infradian rhythms also include annual rhythms , which will be discussed sepa-rately in Section 4.4. 4.3.1 E STROUS C YCLE Animal reproduction generally requires the joining of male sperm with a female egg. Most female animals do not ovu-late on demand, so that reproduction is possible only during the appropriate phase of the ovulatory cycle. 127 As you prob-ably know, many young humans take advantage of this fact and indulge in sexual activity during most of the ovulatory cycle of the woman without having to worry about contracep-tion. 128,129 A woman’s estrous cycle—as the estrous cycle of other female primates—is called a menstrual cycle because the cycle lasts about a month ( mense means month in Latin). However, there is nothing special about the month. As shown in Table 4.2, estrous cycles vary from 1 day in domestic fowl to 220 days in dogs. - eBook - PDF

- Simon Green(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Red Globe Press(Publisher)

23 Biological rhythms Chapter 2 Introduction The natural world is full of rhythms, patterns of activity. The sea has high and low tides each day. Some plants, such as morning glory, flower regularly, but only in the evenings. Some beach-living worms burrow down when the tide comes in, and emerge when it goes out again. The human female menstrual rhythm is a regular monthly cycle. Many animals hibernate each winter. As the cold weather approaches, these animals prepare by laying down extra body fat and becoming less active. Day-living ( diurnal ) animals sleep when it becomes dark and awake when morning arrives. Night-living ( nocturnal ) animals are alert and active at night and sleep during daylight. Humans are diurnal creatures, accustomed to sleeping at night-time and staying awake during daylight hours. Even during sleep, we can iden-tify rhythmic activity; humans and many other animals show a regular oscillation between different phases of sleep, including periods of ‘dreaming’ sleep. We can therefore identify literally thousands of rhythms across the living world. Some, such as the stages of sleep, occur in less than 24 hours; this frequency, or periodicity, is known as ultradian . The majority of biological rhythms have a periodicity of 24 hours, and these are known as circadian . Rhythms taking longer than 24 hours are known generally as infradian rhythms, with those such as hibernation, with a periodicity of one year, known as circannual . This chapter will be describing many of these rhythms, focusing on why they evolved and how they are controlled. We will concentrate on sleep in particular, partly because it has been the most researched, and 24 Biological Rhythms, Sleep and Hypnosis partly because it is the most fascinating. - eBook - PDF

- Thomas Brown(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

They may occur night after night, month after month, year after year, with such regularity that they may be easily overlooked by researchers interested in the physi-ological bases of behavior. But biological rhythms have some very important effects on our behavior. Figure 13.1 diagrams a hypothetical rhythm which will be useful in explaining some of the terms used to discuss biological rhythms. Any event which changes from one point and eventually returns to that point can be thought of as a rhythm, regardless of how long it actually takes. The time which is required for the rhythm to complete a cycle is called the period. The frequency of the rhythm is the reciprocal of the period. For example, body temperature reaches a peak once every 24 hours. So the period is 24 hours, and the frequency for this rhythm is 1/24. The amount of change from the original starting point may also be important; the amplitude of a rhythm refers to this amount of change. For example, some people may only have body temperature fluctuations of 2 degrees during the 24 -hour period, but others may have a cycle with a higher amplitude, perhaps 5 degrees. Also, indi-viduals may differ in when their body temperatures peak. The term phase is used to locate the peak or trough of a cycle with reference to some external marker, such as a particular time of day. A person whose body temperature peaks at 4 P.M . would be out of phase with a person whose temperature peaks at 2 P.M. The biological rhythms in humans which have received the most attention are the circadian rhythms, with a period of about 24 hours, and the female's 28 -day menstrual cycle. Since we discussed the fe-male's rhythm in the last chapter, we will concentrate on circadian rhythms in this one. In the first section, we will explore the changes which occur in the normal individual across the 24 -hour cycle. - eBook - PDF

- Dennis E. Buetow(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Inasmuch as the latter three types of functional biochronometry may represent evolutionarily more re-cent and sophisticated variations on a more basic adaptation to the 24-hour day, an understanding of the nature of circadian ''clocks may be crucial to the elucidation of these higher-level phenomena (Palmer et al., 1976). The generally accepted properties of circadian rhythms, having a period of about one day, are summarized in Fig. 1. Unless otherwise noted, the term circadian will refer only to those biological periodicities that have been demon-strated to persist for at least several cycles following removal of the synchroniz-ing, or entraining, regimen of light, temperature, or other Zeitgeber. Our central thesis is that there is a selective premium for temporal adaptation, especially to solar periodicities, and that these adaptive features have been attained by or-ganisms through some sort of timing mechanism, in particular, an endogenous, 3. Circadian and Infradian Rhythms 55 autonomously oscillatory biological clock which is responsive to and which can be reset and otherwise modulated by those environmental periodicities that the organism has encountered throughout its evolutionary history (Palmer et al., 1976). The following books and symposia provide major treatment of biological rhythms: Frisch (1960); Goodwin (1963); Aschoff (1965); Menaker (1971); Sweeney (1969a; 1972); Bunning (1973); Pavlidis (1973); Scheving et al. (1974); Palmer et al. (1976); Goodwin (1976); Hastings and Schweiger (1976); Saunders (1976); Krieger (1979); Wever (1979); Scheving and Halberg (1980); and the Proceedings of the XIII, XIV, and XV International Conferences of the International Society for Chronobiology (in press). A. TEMPORAL ORGANIZATION OF Euglena Circadian organization is not restricted to multicellular organisms. - Bozzano G Luisa(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Endogenous rhythms can be broadly categorized as simple or circa. Simple endogenous rhythms, such as the cardiac cycles, are not synchronized to any particular external environmental fluctuation. Circa-rhythms, on the other hand, are adapted to and influenced by geophysical environmental cycles. Four such circa-rhythms have been identified, each associated with a characteristic cycle time or period: circatidal (about 12 hr), circadian (about 24 hr), circalunar (about 28 days), and circannual (about 1 year). The extreme prevalence of circadian rhythms in eukaryotic organisms has led to categorizing other endogenous rhythms in relation to 24-hr cycles: ultradian rhythms are biological cycles with periods «20 hr whereas infradian rhythms have periods »30 hr. An example of an ultradian rhythm would be the 90-min REM-nonREM cycle in human sleep; the 4- to 5-day estrous cycles in rats and hamsters would be considered infradian rhythms. 292 Donald L. McEachron and Jonathan Schull In the presence of appropriate entraining stimuli (a light-dark cycle, for example), the frequency and phase relations of circa-rhythms can be synchronized and aligned with the environmental rhythm. However, when such Zeitgebers (literally, in German, time-givers) are eliminated in the laboratory (e.g., under conditions of constant light or constant darkness), circa-rhythms free run with periods close to, but not equal to, that of their geophysical cycle. The phase of the endogenous oscillation (often defined by the time at which the biological cycle peaks) gradually drifts away from that of the geophysical oscillation, thus pro-viding the clearest evidence for an endogenous oscillator whose fluctuations are not driven but only synchronized by environmental cues. Thus, by definition, all endogenous circa-rhythms can free run under constant conditions. Under natural circumstances, however, organismic and environmental rhythms are typically synchronized or entrained.- eBook - PDF

- Graham Scott(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Circannual rhythms Many species of animal demonstrate periods of behavior with a one-yearly repeating cycle. For example, the passerine birds that migrate into the northern temperate regions of the world to breed exhibit an annual cycle of testicular growth and regression and demonstrate regular molting cycles that have been shown experimentally to be under endogenous control. During the colder winter months these birds return to their southern winter-ing grounds, but migrations of this kind are not an option for all temperate animal species. Those that cannot remain active in the face of the adverse conditions that winter brings must adopt a different strategy. Many undergo an annual hibernation that is often associated with prehibernation hyperphagia and shelter-seeking behaviors such as burrow or roost site preparation. Experimental work has confirmed that this phenomenon too is under endogenous control (Plate 3.1). Longer and shorter rhythms The performance of a great many behaviors demonstrates the existence of a clearly defined rhythm that cannot be described as being either circadian or circannual. Those that have a cycle shorter than 24 hours are termed infradian rhythms and those Link The onset of migration is controlled by a biological clock. Chapter 4 Plate 3.1 The autumnal burrowing behavior of this Mediterranean tortoise is under endogenous control. © G. Scott. Motivation and Organization of Behavior 51 having a periodicity that is longer than a day are called ultradian rhythms. For example the environment of intertidal animals changes dramatically with the twice-daily ebb and flow of the tide. Not surprisingly many of the behavioral rhythms of these animals are in phase with the tidal cycle, having a periodicity of a little over 12 hours. - eBook - ePub

Bipolar Disorder

Clinical and Neurobiological Foundations

- Lakshmi N. Yatham, Mario Maj, Lakshmi N. Yatham, Mario Maj(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

The aim of this review chapter is to encourage further research into these important pathways, by tracing the limits of scientific knowledge about biological rhythms in BD. We first outline the basics of circadian rhythms and sleep, highlighting the challenge of empirically separating these two factors. Subsequently, literature on circadian- and sleep-moderation of emotion is reviewed, largely focusing on non-clinical populations. Evidence for an association between biological rhythms and BD is detailed next, and causal inferences considered. The following section considers potential mechanisms of biological rhythm action in BD, particularly the impact of clock genes. Finally, we introduce clinical implications of the fact that biological rhythmicity is modified by behaviour (Section 20.6).Circadian rhythms and sleep Circadian systemThe endogenous circadian time-keeping system, strongly conserved across species, is adapted to optimize engagement with the earth’s cyclic environment by predicting critical environmental change [6]. In mammals, the circadian pacemaker responsible for the temporal internal organization and generation of endogenous rhythms of approximately 24 h is located in the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN, [7]).2 At the molecular level, intrinsically rhythmic cells of the SCN generate self-sustained rhythmicity via an auto-regulatory transcription-translation feedback loop regulating expression of the Period (Per1, Per2, Per3) , cryptochrome(Cry1 , Cry2 ), TIM, DEC1 and DEC2 genes [8].3The endogenous period generated in the SCN is close to, but generally not equal to 24-hour. The process by which the pacemaker is both set to a 24-hour period and kept in appropriate phase with seasonally shifting astronomical day length is called entrainment. An important property of the circadian system, therefore, is its fundamentally open nature, and this open nature includes feedback to the pacemaker from clock-controlled activity of the organism [10]. Entrainment occurs via zeitgebers (environmental events that can affect phase and period of the clock), the most prominent of which is the daily alteration of light and dark due to the planet’s rotation [11]. To a lesser degree, the SCN is also responsive to non-photic - eBook - PDF

- Jon C. Horvitz, Barry L. Jacobs(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Some genetic evi- dence suggests that these characteristics may run in families. 5.2 STAGES OF SLEEP 197 The study of circadian rhythms also helps us to understand jet lag. Say that your flight departs New York City at 8:00 p.m. and lands in Rome at 8:00 a.m. local time on the following day. In your excitement, you want to rush out immediately to see the Coliseum. However, it’s still only 2:00 a.m. in New York. With your sleep–wake cycle still entrained to New York zeitgebers, your biological clock tells you that you should be in bed. Expo- sure to the bright Roman morning sunshine will cause your internal clock to reset in a few days, i.e., your sleep–wake cycle will eventually entrain to the time cues in Rome. KEY CONCEPTS • Virtually all life on earth is influenced by a circadian cycle of approxi- mately 24 hours. • While typically influenced by external cues such as periods of light and darkness, a biological clock operates in the absence of any external signals. • In mammals, the brain mechanism controlling circadian rhythms is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus. • The degree to which you feel tired depends on an interaction between your biological clock and how long you have been awake. TEST YOURSELF 1. If you were in a cave with no external cues about time of day, would you still show a circadian rhythm? Would you begin to sleep at random times during the day and night? 2. What brain structure is considered the brain’s master clock? 3. Sleep is said to be governed by circadian and homeostatic factors. Ex- plain what this means. 4. After a night without sleep, a person may be very tired at 4:00 a.m. Surprisingly, they may feel less tired at 9:00 a.m., even though they have had 5 additional hours without sleep! Why? 5.2 STAGES OF SLEEP In the sleep laboratory, researchers employ several physiological meas- ures as the individual sleeps. Three key measures are examination of brain waves, muscle activity, and eye movements. - eBook - PDF

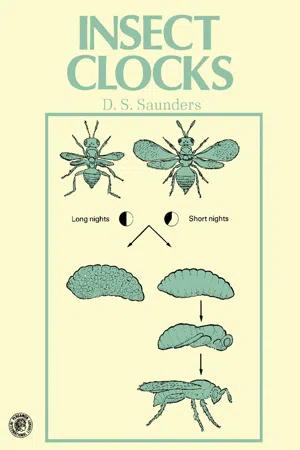

Insect Clocks

Pergamon International Library of Science, Technology, Engineering and Social Studies

- D. S. Saunders(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Pergamon(Publisher)

(1972) have described circadian neurones in the brain which show increased impulse frequency just before the light is turned on and which maintain a high level of activity for 10 to 12 hours thereafter. Clearly, neurophysiological investigations of this kind may provide important insights into the mechanisms control-ling overt rhythmicity. CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS AND PHYSIOLOGY 67 50 10 FIG. 4.3. Changes in the level of RNA synthesis in the neurosecretory cells of the pars intercerebralis of rhythmic house crickets (Acheta domestica) originating from LD 12 : 12 conditions. Open circles: locomotor activity expressed in number of movements per hour; histogram: the intensity of RNA synthesis. (Redrawn from Cymborowski and Dutkowski, 1969.) D. Sensitivity to Drugs and Insecticides Circadian rhythms of sensitivity to drugs were first recorded by Halberg and his associates (Halberg, 1960). At different times of the 24-hour cycle, mice were found to react differently to equivalent doses of Escherichia coli endotoxin, ethanol, ouabaine and the adrenocortical inhibitor, Su-4885. In the case of E. coli endotoxin, for example, highest mortality was recorded (in LD 12: 12) towards the end of the light period and the lowest mortality close to midnight. Similar examples of pharmacological sensitivity are now known in the insects. Beck (1963) maintained the cockroach Blatella germanica in LD 12 : 12 for 7 days and then injected standard doses of DDT, Dimetalan, Dichlorvos and KCN into the haemocoel at different times of the 24-hour cycle. The insects were then held in LL to determine the resulting mortalities. Sensitivity to cyanide (2 g/insect) was highest shortly after dark and lowest soon after dawn. Dimetalan (2.5 g/insect) was most toxic in the middle of the night. The rhythm of sensitivity to Dichlorvos (0.15 g/insect) was bimodal with peaks during the late subjective day and the late subjective night; that for DDT was unimodal but very shallow. - eBook - ePub

- Irving B. Weiner, Randy J. Nelson, Sheri Mizumori(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

The mammalian circadian system undergoes significant change across the lifespan, particularly during early developmental and in later life. The developmental progression of the circadian system includes changes in the endogenous clock responsible for generating intrinsic rhythms, the development of the input pathways responsible for environmental entrainment, as well as output pathways for synchronizing the various oscillators in neuronal and peripheral tissues. The expression of behavioral and physiological circadian rhythms coincides with the completion of neurogenesis in the SCN, its innervation by the retinohypothalamic tract, and the maturation of effector systems. The timing of this process differs significantly in precocial and altricial animals, and thus overt rhythms develop at different developmental stages. Nevertheless, in general, circadian rhythms in most mammalian species are evident prenatally, entrain to the solar day within the first weeks or months of life, and may continue to change across development, particularly during adolescence and old age. In humans, the SCN are formed by the 18th week of gestation, and melatonin receptors are present, suggesting the SCN may be capable of generating self-sustained oscillations. Circadian rhythms of several physiological functions are evident during the prenatal period in altricial species such as humans, rhesus monkeys, and sheep. Human fetuses display circadian patterns in rest-activity, movement, breathing, heart rate, and urine production rhythms (Ruger & Scheer, 2009). In addition, in nonhuman primates and sheep, circadian rhythms of plasma prolactin, cortisol and vasopressin in cerebrospinal fluid are evident in the fetus (Seron-Ferre, Valenzuela, & Torres-Farfan, 2007). In preterm infants, body temperature rhythms are evident in the first days of life, even though these infants are housed under constant environmental conditions. These prenatally observed rhythms are not likely due to the entrainment effects of the mother, since several studies have noted phase differences between mother and fetus.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.