Biological Sciences

Protein Synthesis

Protein synthesis is the process by which cells build proteins. It involves two main stages: transcription, where the DNA sequence is copied into messenger RNA (mRNA), and translation, where the mRNA is used as a template to assemble amino acids into a specific protein. This fundamental process is essential for the growth, repair, and maintenance of living organisms.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Protein Synthesis"

- eBook - ePub

Advanced Molecular Biology

A Concise Reference

- Richard Twyman(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Garland Science(Publisher)

Chapter 23Protein Synthesis

Fundamental concepts and definitions- Protein Synthesis is the level of gene expression where genetic information carried as a messenger RNA (mRNA) molecule is translated into a polypeptide.

- The components of the Protein Synthesis machinery are mRNA, the template which contains the code to be translated, ribosomes, large ribonucleoprotein particles which are the sites of Protein Synthesis, transfer RNA (tRNA), versatile adaptor molecules which carry amino acids to the ribosome and facilitate the process of translation, and accessory factors associating transiently with the ribosome, required for ribosome assembly and disassembly, and its activity during elongation.

- Like other polymerization reactions, Protein Synthesis has stages of initiation, elongation and termination, each of which may be regulated. The Protein Synthesis mechanism is similar in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, but there are subtle differences in the nature of the components and their order of assembly. There are major differences, however, concerning the context in which Protein Synthesis occurs. In bacteria, transcription and Protein Synthesis occur simultaneously in the cytoplasm (allowing cross-regulation between different levels of gene expression) and mRNA may be polycistronic. In eukaryotes, transcription is confined to the nucleus and the mRNA is exported to the cytoplasm for translation. Nascent mRNA is extensively processed before export and is usually monocistronic (see RNA Processing).

- Following synthesis, a polypeptide undergoes further processing before becoming active. It must fold correctly, a process sometimes requiring the assistance of a molecular chaperone (q.v.). It may be cleaved, and specific residues may be chemically modified or conjugated to small molecules. Such modifications are often associated with the targeting of proteins to specific compartments in the cell or for secretion. Proteins may need to associate noncovalently with other proteins or with nonpolypeptide cofactors for their full activity. For a discussion of these processes, see

- eBook - PDF

Protein Deposition in Animals

Proceedings of Previous Easter Schools in Agricultural Science

- P.J. Buttery, D.B. Lindsay(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Butterworth-Heinemann(Publisher)

1 MECHANISM AND REGULATION OF PROTEIN BIOSYNTHESIS IN EUKARYOTIC CELLS VIRGINIA M. PAIN Department of Human Nutrition, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and MICHAEL J. CLEMENS Department of Biochemistry, St George's Hospital Medical School, London Summary Protein biosynthesis comprises a series of complex processes involving three kinds of RNA and a large number of proteins. Messenger-RNA (mRNA) carries in its nucleo-tide sequence a code determining the order of insertion of amino acids into the poly-peptide chain. Ribosomal-RNA, in combination with about 70 proteins, is formed into an organelle, the ribosome, which provides the correct structural alignment for the other protein synthetic components. Transfer-RNA (tRNA) exists as a number of different species, each specific for a particular amino acid, and is involved in activating and binding successive amino acids to the ribosome in the order directed by the structure of messenger-RNA (also bound to ribosomes). Protein factors involved in Protein Synthesis include many which function enzymically and others which have more structural significance. The overall process, referred to as translation, is divided into three stages: (1) Initiation. A ribosome and a molecule of a specific initiator tRNA (Met-tRNAf) bind to a particular site on the mRNA at the beginning of the coding sequence. Another aminoacyl-tRNA is then able to bind, and synthesis of the first peptide bond takes place. (2) Elongation. The ribosome moves relative to the messenger-RNA and a polypeptide chain is elaborated from amino acids in a specific sequence directed by the order of nucleotides in the messenger-RNA. (3) Termination. The ribosome reaches the end of the coding sequence on the messenger-RNA and is released together with the completed protein chain. In most tissues in vivo each molecule of messenger-RNA is translated simultaneously by several ribosomes, the entire structure being termed a polyribosome or polysome. - eBook - ePub

- Pascal Leclair(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

8 Protein Synthesis Part II The Mechanism of Protein TranslationDOI: 10.1201/9781003379058-8In 1957, Francis Crick gave what would become a most significant lecture on Protein Synthesis at University College London during a Society for Experimental Biology symposium on the “Biological Replication of Macromolecules”. In the hour-long lecture, which is now referred to as the “Central Dogma” lecture and about which is said to have permanently altered the logic of biology,1 Crick summarized the development in protein research with an emphasis on the mechanism of Protein Synthesis and makes clear that proteins’ role in cells is at least of equal footing as that of DNA:It is an essential feature of my argument that in biology proteins are uniquely important. They are not to be classed with polysaccharides, for example, which by comparison play a very minor role. Their nearest rivals are the nucleic acids. Watson said to me, a few years ago, ‘The most significant thing about the nucleic acids is that we don’t know what they do.’ By contrast the most significant thing about proteins is that they can do almost anything. In animals proteins are used for structural purposes, but this is not their main role, and indeed in plants this job is usually done by polysaccharides. The main function of proteins is to act as enzymes. Almost all chemical reactions in living systems are catalysed by enzymes, and all known enzymes are proteins. It is at first sight paradoxical that it is probably easier for an organism to produce a new protein than to produce a new small molecule, since to produce a new small molecule one or more new proteins will be required in any case to catalyse the reactions. - eBook - PDF

- Ulo Langel, Benjamin F. Cravatt, Astrid Graslund, N.G.H. von Heijne, Matjaz Zorko, Tiit Land, Sherry Niessen(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

61 4 The Biosynthesis of Proteins Matjaž Zorko 4.1 ASSEMBLY OF THE PRIMARY STRUCTURE The protein structure in DNA is coded by the genetic code, with the exception of some viruses that use RNA for this purpose. A very complex cell apparatus has evolved to translate the language of nucleotides in DNA into the language of amino acids in proteins. A multistep biosynthesis of the polypeptide chain starts with the transcription of DNA into RNA. The transcribed RNA, called the primary tran-script, is then transformed in a series of molecular events into the mRNA, which is used as a template for the next step of the biosynthesis, termed translation. This step takes place in the ribosome and is assisted by a large number of accessory proteins, tRNAs, and energy-providing molecules. The three-step procedure of the protein biosynthesis is basically the same in all organisms. All the steps of the protein biosynthesis are strictly regulated in order to get the proper repertoire of functional proteins present in the cells and in the extracellular solutions. Recently, techniques have been developed to additionally include into the protein sequence some of the noncoded amino acids in order to design and produce proteins with novel functions. In addition to the proteins, the majority of physiologically important peptides are also synthesized via a transcription and translation process; however, some of the important peptides are assembled nonribosomally via a series of enzyme-catalyzed reactions. CONTENTS 4.1 Assembly of the Primary Structure ................................................................. 61 4.1.1 The Genetic Code ............................................................................... 62 4.1.2 Transcription of DNA to mRNA ......................................................... 63 4.1.3 Translation of mRNA to the Polypeptide Chain ................................. - eBook - ePub

- David P. Clark(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Academic Cell(Publisher)

3 for a brief overview). The genetic information is transmitted in two stages. First the information in the DNA is transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA). The next step uses the information carried by the mRNA to give the sequence of amino acids making up a polypeptide chain. This involves converting the nucleic acid “language,” the genetic code, to protein “language,” and is therefore known as translation. This overall flow of information in biological cells from DNA to RNA to protein is known as the central dogma of molecular biology (see Chapter 3, Fig. 3.17) and was first formulated by Sir Francis Crick. Ribosomes use the information carried by messenger RNA to make proteins. The decoding of mRNA is carried out by a submicroscopic machine called a ribosome, which binds the mRNA and translates it. The ribosome moves along the mRNA reading the message and synthesizing a new polypeptide chain. Bacterial Protein Synthesis will be discussed first. The process is similar in higher organisms, but some of the details differ and will be considered later. Proteins Are Gene Products An early rule of molecular biology was Beadle and Tatum’s dictum: “one gene—one enzyme” (see Ch. 1). This rule was later broadened to include other proteins in addition to enzymes. Proteins are therefore often referred to as “gene products.” However, it must be remembered that some RNA molecules (such as tRNA, rRNA, small nuclear RNA) are never translated into protein and are therefore also gene products. Gene products include proteins as well as non-coding RNA Furthermore, instances are now known where one gene may encode multiple proteins (Fig. 8.01). Two relatively widespread cases of this are known—alternative splicing and polyproteins. In eukaryotic cells, the coding sequences of genes are often interrupted by non-coding regions, the introns. These introns are removed by splicing at the level of messenger RNA - eBook - PDF

Chemistry for Today

General, Organic, and Biochemistry

- Spencer Seager, Michael Slabaugh, Maren Hansen, , Spencer Seager, Spencer Seager, Michael Slabaugh, Maren Hansen(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

The appropriately named messenger RNA carries the in- formation (the message) from the nucleus to the site of Protein Synthesis in the cellular cytoplasm. In the second step, the mRNA serves as a template on which amino acids are assembled in the proper sequence necessary to produce the specified protein. This takes place when the code or message carried by mRNA is translated into an amino acid sequence by tRNA. There is an exact word-to-word translation from mRNA to tRNA. Thus, each word in the mRNA language has a corresponding word in the amino acid language of tRNA. This communicative relationship between mRNA nucleotides and amino acids is called the genetic code (see Section 21.7). Figure 21.17 summarizes the mechanisms for the flow of genetic information in the cell. central dogma of molecular biology The well-established process by which genetic information stored in DNA molecules is expressed in the structure of synthesized proteins. transcription The transfer of genetic information from a DNA molecule to a molecule of messenger RNA. translation The conversion of the code carried by messenger RNA into an amino acid sequence of a protein. DNA replication DNA RNA protein Transcription Translation FIGURE 21.17 The flow of genetic information in the cell. Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 688 Chapter 21 21.6 Transcription: RNA Synthesis Learning Objective 6 Describe the process by which RNA is synthesized in cells. An enzyme called RNA polymerase catalyzes the synthesis of RNA. - eBook - ePub

- Anders Liljas, Lars Liljas;Miriam-Rose Ash;G?ran Lindblom;Poul Nissen;Morten Kjeldgaard(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- WSPC(Publisher)

11Protein Synthesis â Translation

11.1Evolution of the Translation System

The translation of genetic information into functional protein molecules is a central process for life; and the genetic code, tRNA molecules and the machinery for Protein Synthesis are all highly conserved. The ribosome on which translation occurs is composed of protein and rRNA molecules. Carl Woese showed that sequenced fragments of ribosomal rRNA molecules from a large variety of species were related. Thus, the ribosomal RNAs could be used to analyze the relationship between species. By 1977, he could show that it was not correct to divide the present living organisms into prokaryotes and eukaryotes. A unique new kingdom had to be introduced: archaea. Living organisms, according to Woese, had to be organized into bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes.In comparisons of completely sequenced genomes, the molecules of the translation apparatus stand out as dominating the group of universally conserved molecules. The genetic code, tRNAs, ribosomal rRNA, ribosomal proteins and translation factors must have coevolved at a very early phase of biological evolution and have subsequently gone through only limited further changes.An important aspect of Protein Synthesis is that nucleic acid molecules have central roles, in contrast to most other processes in cells where proteins dominate. Central components are the mRNA, the tRNA and the ribosomal rRNA molecules. An mRNA molecule contains a copy of the gene sequence and binds to the ribosome. The tRNA molecules, the adapters suggested by Francis Crick, decode the gene sequence and link the amino acid into the growing peptide on the ribosome.Fig. 11.1 ▪ - eBook - ePub

Amino Acids

Biochemistry and Nutrition

- Guoyao Wu(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Yin et al. 2010 ). In essence, Protein Synthesis represents a major physiological process for AA utilization in cells. In this chapter, the pathway of intracellular Protein Synthesis in animals will be described along with its characteristics, significance, and measurement.8.1 Historical Perspectives of the Protein Synthesis Pathway

The history of studies of the metabolic pathway responsible for protein biosynthesis dates back to the late 1930s when T. Caspersson and J. Brachet found that DNA is localized almost exclusively in the nucleus of the eukaryotic cell, whereas RNA is present primarily in the cytoplasm. J. Brachet also noted that the RNA-containing particles in the cytoplasm are rich in proteins and suggested that these particles are the site of Protein Synthesis. In 1941, both authors further observed that the amount of cytosolic RNA-protein complexes (later named ribosomes) is positively correlated with the rate of Protein Synthesis. The 1950s witnessed rapid advances in the field, including (1) K. Porter’s discovery in 1952 of the endoplasmic reticulum (an organelle that consists of an interconnected network of tubules, vesicles, and cisternae) in eukaryotes, with the rough endoplasmic reticulum being involved in Protein Synthesis; (2) G.E. Palade’s description of ribosomes consisting of RNA-protein complexes in 1953; (3) G. Gamow’s suggestion of a minimum genetic code of three nucleotides in 1954; (4) isolation by M. Grunberg-Manago and S. Ochoa of the enzyme which links RNA nucleotides to form RNA in vitro in 1955; (5) the report by A. Kornberg in 1956 that enzymes are necessary for DNA synthesis in vitro; and (6) the discoveries by M.B. Hoagland and coworkers that separate enzymes catalyze the activation of different AAs for incorporation into peptides (1956), that cells contain tRNA, which combines with AAs before Protein Synthesis (1957), and that the DNA polymerase isolated from E. coli could catalyze DNA synthesis in vitro. In 1958, A. Tissières and J.D. Watson isolated 70S ribosomes from E. coli - eBook - PDF

- Pat Willmer, Graham Stone, Ian Johnston(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

The number of possible proteins that could theoretically be formed by the normal 20 amino acids transcribed in animals is staggering (20 n , where n is the chain length; this gives a value of 160,000 for just four amino acids, and 10 390 for a more typical chain of 300 amino acids). Yet very few of these possibilities exist natu-rally. This is probably largely because very few of them would be stable in three dimensions; many would form straggly molecules with many different possible conformations, which would be impossibly difficult to control. The proteins that are selected for in evolution are those that can reliably and repeatably fold up into stable forms, where small conformational changes can be controllably achieved to perform specific structural or catalytic functions. 2.3.2 Controlling Protein Synthesis In any cell at any particular time some of the DNA is being used to make very large amounts of RNA and other parts are not being tran-scribed at all. Transcription is controlled by an RNA polymerase enzyme, which makes RNA copies of DNA molecules (though in fact the full “transcription initiation complex” comprises the poly-merase and at least seven other proteins). A polymerase appears to act by colliding randomly with DNA molecules but only sticking tightly when it contacts a specific region of DNA termed a pro-moter , which contains the “start sequence” signaling where RNA synthesis should begin. It opens up the DNA double helix here and then moves along the DNA strand in the 5 ′ to 3 ′ direction, at any one time exposing just a short stretch of unpaired DNA nucleotides. Eventually it meets a stop signal, and releases both the DNA tem-plate and the new RNA chain. Figure 2.6 shows the organization of a promoter and the five genes that it controls, all of them involved in a particular pathway (in this case tryptophan synthesis in the bacterium Escherichia coli ). - eBook - PDF

- S Bresler(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

The great stability of rRNA was shown in experiments of the following design. When a bacterial culture is grown in the presence of heavy isotopes and then transferred to light medium, isotopically labeled rRNA is transmitted to progeny cells without alteration, and can be detected in its original form even in the fourth and fifth generations. The isotopic composition of the inherited RNA does not change in the least, although all of the new components synthesized by the growing cells contain light constituents. In all cells, regardless of their origin, the participation of ribosomes in Protein Synthesis is obligatory. Ribosomes have even been found in the nuclei of cells from higher organisms where they mediate the synthesis of specific nuclear proteins. As with other cellular organelles, ribosomes separate a particular chemical reaction in space from others taking place concurrently in the same milieu. For example, amino acids, the building blocks of protein, can take part in many cellular processes since they are present in the cytoplasm as soluble compounds. The reactions leading to Protein Synthesis must therefore be separated spatially from oxidative or degradative reactions. This explains why distinct organelles are necessary for Protein Synthesis. Generally speaking, they must also be accessible only to essential substances in the cytoplasm such as amino acids and the compounds which mediate energy transfer, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and guanosine triphosphate (GTP). A second type of RNA, called template or messenger RNA, carries genetic infor-mation from the chromosomal DNA to the sites of Protein Synthesis, that is, to the ribosomes where it becomes bound. Such RNA molecules apparently act as a template which directs the assembly of polypeptide chains. Messenger RNA is rapidly meta-bolized in bacterial cells throughout exponential growth ; its synthesis requires 20 to 30 seconds and it is generally degraded in the course of a few minutes. - eBook - PDF

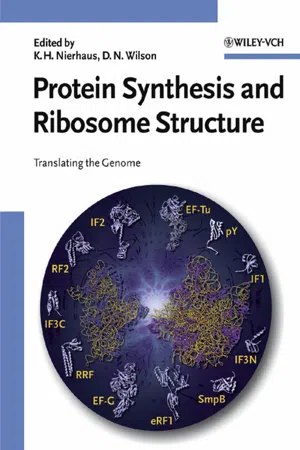

Protein Synthesis and Ribosome Structure

Translating the Genome

- Knud H. Nierhaus, Daniel Wilson, Knud H. Nierhaus, Daniel Wilson(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Wiley-VCH(Publisher)

4 P. C. Zamecnik, Historical aspects of Protein Synthesis, Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1979, 325, 269–301. 5 P. Siekevitz, P. C. Zamecnik, The ribosome and Protein Synthesis, J. Cell. Biol. 1981, 91 (3), 53S–65S. 6 F. Jacob: The Statue Within, Basic Books, New York 1988. 7 F. H. C. Crick: What Mad Pursuit, Basic Books, New York 1988. 8 M. Nomura: History of Ribosome Research: A Personal Account, in The Ribosome. Structure, Function and Evolution, eds W. E. Hill, P.B. Moore, A. Dahlberg et al., ASM Press, Washington, DC 1990, 3–55. 9 A. Spirin: Ribosome Preparation and Cell-free Protein Synthesis, in The Ribosome. Structure, Function and Evolution, eds W. E. Hill, P.B. Moore, A. Dahlberg et al., ASM Press, Washington, DC 1990, 56–70. 10 M. Hoagland: Toward the Habit of Truth, W. W. Norton and Company, New York 1990. 11 F. H. Portugal, J. S. Cohen: A Century of DNA, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA 1977. 12 H. F. Judson: The Eighth Day of Creation, Simon and Schuster, New York 1979. 13 H.-J. Rheinberger: Experiment, difference, and writing. I. Tracing Protein Synthesis, and II. The laboratory production of transfer RNA, Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. 1992, 23, 305–331, 389–422. 14 H.-J. Rheinberger, Experiment and orientation: early systems of in vitro Protein Synthesis, J. Hist. Biol. 1993, 26, 443–471. 15 H.-J. Rheinberger, From microsomes to ribosomes: ‘strategies’ of ‘represen- tation’, J. Hist. Biol. 1995, 28, 49–89. 16 R. M. Burian, Task definition, and the transition from genetics to molecular genetics: aspects of the work on Protein Synthesis in the laboratories of J. Monod and P. Zamecnik, J. Hist. Biol. 1993, 26, 387–407. 17 M. Morange: Histoire de la biologie moléculaire, Editions La Découverte, Paris 1994. 18 L. E. Kay: Who Wrote the Book of Life? A History of the Genetic Code, Stanford University Press, Stanford 2000. 19 Symp Quant Biol 1969, 34 : The Mechanism of Protein Synthesis. 20 M. Nomura, A. Tissières, P. Lengyel (eds): Ribosomes, Cold Spring Harbor, New York 1974.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.