Biological Sciences

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is a contagious bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It primarily affects the lungs but can also affect other parts of the body. Symptoms include coughing, chest pain, weight loss, and fatigue. Tuberculosis is spread through the air when an infected person coughs or sneezes. Treatment typically involves a combination of antibiotics taken over several months.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Tuberculosis"

- eBook - PDF

Tuberculosis

The Essentials, Fourth Edition

- Mario C. Raviglione(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

3 Pathogenesis of Tuberculosis: New Insights NICHOLAS A. BE and WILLIAM R. BISHAI Center for Tuberculosis Research, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.A. SANJAY K. JAIN Center for Tuberculosis Research, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.A. I. Introduction Mycobacterium Tuberculosis , the cause of human Tuberculosis (TB), has been a scourge of humanity throughout recorded history. Even today, this bacillus claims about two million lives per year, remains one of the leading causes of death among the infectious diseases (1,2) and is the leading killer of people with AIDS (3). Human Tuberculosis is a multistage disease. Any rational approach to TB control must be based upon the pathogenic processes at work during these stages. The pathogenic process begins with inhalation of infectious aerosols. Bacilli lodged in the alveoli are engulfed by the alveolar macrophages. If the bacteria are able to survive this initial encounter with the innate immune system, a period of logarithmic growth ensues, with bacterial doubling every 24 hours. Bacteria released from macrophages are engulfed by new macrophages attracted to the site, thereby continuing this cycle. The bacilli may spread from the initial lesion via the lymphatic and/or circulatory systems to other parts of the body. After approximately four to six weeks, the host develops specific immunity to the bacilli. The resulting M. Tuberculosis -specific lymphocytes migrate to the site of infection, surrounding and activating the macrophages there. As the cellular infiltration continues, the center of the cell mass, or granuloma, becomes caseous and necrotic (Fig. 1). - eBook - PDF

- Philip Hasleton, Douglas B. Flieder(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Chapter 6 Pulmonary mycobacterial infections Luciane Dreher Irion and Mark Woodhead Introduction Tuberculosis (TB) is the name given to a spectrum of clinical syndromes caused by a small number of mycobacterial species of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis complex. Most of the other 130 described mycobacterial species are environmental organisms of which a few can cause disease only in very specific circumstances. These are principally associated with impaired host defense. M. Tuberculosis, and less commonly the other organisms of the M. Tuberculosis complex, M. bovis, M. africanum and M. microti, by contrast, can affect immuno- competent individuals, and are highly effective pathogens. Evidence to support this statement comes from history, inclu- ding archeological evidence of TB in bony human remains from 500 000 years ago. That one-third of the current world’s population is estimated to be infected with TB is further evidence. In addition, the global human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic amplifies the importance of tuberculous infection, as co-infection is quite common. Infection with M. Tuberculosis may lead immediately to progressive clinical illness, but it may also be asymptomatic or cause a minimal self-limiting illness. The organism then lies dormant in macrophages (latent infection). In 10% of such latent cases the disease reactivates. Clinical Tuberculosis can affect any organ system, but the lungs and lymph nodes are most commonly affected in the UK. 1 Tuberculosis is curable, yet 1.6 million people died from the disease in 2005. The key steps in TB management are the detection and appropriate treatment of infectious cases, as well as detection and management of latent infection. Cure requires compliance with a prolonged course of multi- tablet treatment with a high frequency of side effects. Mycobac- terial resistance to one or more drugs makes treatment failure more likely and successful treatment more complex and expen- sive. - eBook - PDF

- Carol A. Dyer(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

1 Tuberculosis: Contagion and Cause I n spite of the fact that Tuberculosis (abbreviated TB for tubercle bacilli—the name of the microorganism that causes TB) is a treatable and curable disease, it is currently the second most common cause of death from infectious disease in the world. This blatant contradiction seems to invite an obvious inquiry—if doctors know how to cure TB, why is it still such a deadly problem? Like TB itself, the answer to this question is complicated, multifaceted, and extremely relevant to the current state of health around the world. TB has existed since the beginning of time. Its profile and history have con- founded science and society throughout the ages. The medical tools now exist to make TB a disease of the past, but it still flourishes in places where poverty thrives and health care systems are inadequate and inefficient. TB is a traitor and a scavenger—it sneaks in and lies in wait, it can change itself in order to survive, and it bullies the weak and the poor. Understanding the relationship between the physical and social aspects of TB first requires knowledge of the disease. THE MYCOBACTERIUM Tuberculosis Bacteria are round, spiral, or rod-shaped single-cell microorganisms that typi- cally live in soil, water, organic matter, or the bodies of plants and animals. They 2 Tuberculosis are individual living systems that are too small to be seen without the aid of a microscope, but they are capable of reproduction, growth, and reaction to stim- uli. To organize these microorganisms within the field of biology, bacteria have traditionally been classified by name and grouped on the basis of their features, such as cell structure, cellular metabolism, or cellular components. Beyond this traditional system, modern classification emphasizes the molecular characteris- tics of bacteria; because information about genetics is constantly being updated, bacterial classification remains a changing and expanding field. - eBook - PDF

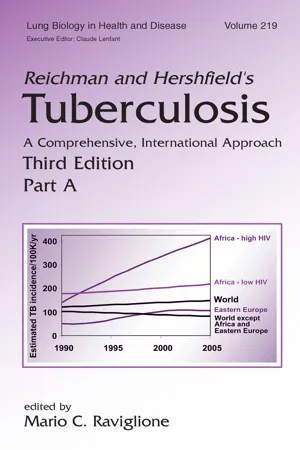

Reichman and Hershfield's Tuberculosis

A Comprehensive, International Approach

- Lee B. Reichman, Earl S. Hershfield(Authors)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

5 Overview of the Pathogenesis of Tuberculosis from a Cellular and Molecular Perspective SAMUEL C. WOOLWINE and WILLIAM R. BISHAI Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Center for Tuberculosis Research, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.A. I. Introduction Mycobacterium Tuberculosis , the cause of human Tuberculosis (TB), has been a scourge of humanity throughout recorded history. Even today, this bacille claims 2 to 3 million lives per year, remains one of the leading causes of death among the infectious diseases (1), and is the leading killer of peo-ple with AIDS (2). Human TB is a multistage disease. Any rational approach to TB control must be based upon the pathogenic processes at work during these stages. The pathogenic process begins with the inhalation of infectious aero-sols. Bacille lodging in the alveoli are engulfed by the alveolar macrophage (AM) and, if able to survive this initial encounter with the innate immune system, begin a period of logarithmic growth, doubling every 24 hours until the macrophage bursts to release the bacterial progeny. New macrophages attracted to the site engulf these bacille and the cycle continues. The bacille may spread from the initial lesion via the lymphatic and/or circulatory systems to other parts of the body. After three weeks, the host develops specific immunity to the bacille. The resulting M. Tuberculosis –specific lymphocytes migrate to the site of 101 infection, surrounding and activating the macrophages there. As the cellular infiltration continues, the center of the cell mass, or granuloma, becomes caseous and necrotic (Fig. 1). In the majority of cases, the immunocompetent human is able to arrest the growth of the bacille within the primary lesion with little or no signs of illness. The initial lesion, which eventually resolves or calcifies, may still har-bor viable bacille, in which case the host is said to harbor latent TB infection (LTBI, see below). - eBook - PDF

- Rachel L. Chin, Bradley W. Frazee, Zlatan Coralic(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

308 Chapter 308 Outline Introduction and Microbiology 308 Epidemiology 308 Pathogenesis and Risk Factors 309 Clinical Features 309 General Manifestations of Tuberculosis 309 Pulmonary Tuberculosis 310 Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis 310 Latent Tuberculosis Infection 310 Differential Diagnosis 310 Laboratory and Radiographic findings 311 Radiographic Features 311 Latent Tuberculosis Infection 311 Microbiologic Diagnosis: Pulmonary Tuberculosis 311 Microbiologic Diagnosis: Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis 312 Treatment 312 General Principles 312 Treatment of Drug-Susceptible Disease 313 Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection 313 HIV Infection and Tuberculosis Treatment 316 Treatment of Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis 316 Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis 316 Complications and Admission Criteria 316 Infection Control 316 Pearls and Pitfalls 317 References 317 Additional Readings 318 Tuberculosis Robert Blount, Payam Nahid, and Adithya Cattamanchi 47 Introduction and Microbiology Mycobacterium Tuberculosis is a large, non-motile, curved rod that causes the vast majority of human Tuberculosis cases. M. Tuberculosis and three very closely related mycobacterial species (M. bovis, M. africanum, and M. microti) all cause tuberculous disease, and they comprise what is known as the M. Tuberculosis complex. M. Tuberculosis is an obligate aerobe, accounting for its predilection to cause disease in the well- aerated upper lobes of the lung. However, M. Tuberculosis can persist in a dormant state for many years even with a limited oxygen supply. The organisms also persist in the environment and are resistant to disinfecting agents. Mycobacterium species are classified as acid-fast organisms because of their ability to retain certain dyes when heated and treated with acidified compounds. Humans are the only known reservoir of infection. Epidemiology Tuberculosis has surpassed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) as the leading cause of death related to an infectious disease. - eBook - PDF

- Norma Whittaker(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Red Globe Press(Publisher)

Tuberculosis N ORMA W HITTAKER The World Health Organization (WHO) in 1993 took the unprecedented step of declaring Tuberculosis (TB) a global emergency. Not only has Tuberculosis re-emerged in developed countries, but also the world has been introduced to multidrug resistant Tuberculosis (MDR-TB) strains. These are more serious because the course of treatment is longer, more costly and because the TB bacteria are unaffected by at least one of the anti-Tuberculosis drugs still being used today. 273 11 Contents ■ Definition ■ Aetiology ■ Epidemiology ■ Pathophysiology of TB ■ Clinical manifestations ■ Investigative tests ■ Treatment ■ Nursing interventions Learning Objectives By the end of the chapter you should be able to demonstrate knowledge of ■ Factors associated with the epidemiology and aetiology of TB. ■ The potential outcomes for individuals exposed to Mycobacterium Tuberculosis . ■ The pathophysiology of TB and the effects upon the individual. Epidemiology Definition Tuberculosis is an infectious disease that most commonly affects the lungs but it can be transported to any number of sites around the body via the blood or lymphatic system. These include the lymph glands, kidneys, skin, bones, wounds/lesions, meninges and reproductive organs. TB is categorized as either pulmonary or non-pulmonary (Gleissberg, 1996). Aetiology Tuberculosis is an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium Tuberculosis ( M. Tuberculosis ). 274 Tuberculosis ■ The potential for transmitting TB from person to person. ■ How TB is diagnosed and treated. ■ The role of the nurse in screening, contact tracing and encouraging adherence to treatment regimens. ■ Nursing interventions that recognize the need to target high risk groups and deliver appropriate health promotion and education. ■ Nursing interventions that reflect the need to support affected individuals physically and psychologically during lengthy treatment regimens. - eBook - PDF

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- European Respiratory Society(Publisher)

| Chapter 3 Tuberculosis Giovanni Sotgiu 1 , Rosella Centis 2 and Giovanni Battista Migliori 2 TB is an infectious disease caused by strains of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis . It is one of the most important diseases worldwide, together with malaria and HIV/AIDS. The last World Health Organization report highlighted an estimated global incidence of 8.6 million cases ( i.e . 122 cases per 100 000 population) in 2012; the highest figures were estimated in India, China, South Africa, Indonesia and Pakistan. In the majority of the cases, high-income countries show an estimated incidence , 10 patients per 100 000 population. HIV/AIDS plays an important role in the development of TB disease; consequently, geographical areas characterised by an high HIV/AIDS prevalence show a high TB incidence. Disorders which impair the immune system ( e.g. diabetes mellitus or exposure to immunosuppressive drugs) favour the occurrence of pulmonary and/or extrapulmonary forms of TB. A new World Health Organization public health strategy has been recently launched to reduce the global incidence to less than one TB case per 100 000 population by 2050. T B is a serious airborne disease caused by a bacterial agent, named Mycobacterium Tuberculosis [1]. The disease represents one of the clinical outcomes related to the infection. However, the epidemiology of this bacterial infection is complex and not completely understood. Numerous mycobacterial, host and environmental factors can influence the transmission and acquisition of the infection, its latency, the clinical evolution into pulmonary and extrapulmonary forms, or, in case of severe and/or untreated disease, its progression to death (fig. 1) [2]. The global scenario TB, together with HIV/AIDS and malaria, represents an important clinical and public health priority worldwide [3–6]. The administration of anti-TB antibiotics alone has proven to be inefficient as a radical solution to M. - eBook - PDF

- S. H. E. Kaufmann, H. Hahn, B. W. J. Mahy(Authors)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- S. Karger(Publisher)

Kaufmann SHE, Hahn H (eds): Mycobacteria and TB. Issues Infect Dis. Basel, Karger, 2003, vol 2, pp 1–16 Tuberculosis as a Global Public Health Problem Donald A. Enarson International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France Although great advances have been made in the control of Tuberculosis (TB), deaths from this disease are still the equivalent to the crash of a Boeing 747 aircraft every hour of every day [1]. One third of all humans are thought to be infected with the causative organism, Mycobacterium Tuberculosis . TB kills more women than any cause of maternal mortality. The total cost of implement-ing the global control strategy is equivalent to building one large hospital each year in an industrialized country. TB control is the most cost-effective develop-ment assistance for health, and yet, only 0.2% of investment in health in poor countries has been spent on TB services in recent years. The neglect of TB is a scandal that has gone on for decades and is only now beginning to be addressed. Transmission of TB from one person to another takes place from an infec-tious case (the smear-positive pulmonary TB case is the most potent source) to a susceptible, uninfected person. Cases of TB arise either from this large pool of infected persons or from persons with previous disease which had become inactive prior to becoming reactivated. Once involved with this cycle of infec-tion and disease, the only escape leading to no further disease is by death, by modern specific chemotherapy of active disease or by preventive therapy in the absence of current disease. Even then, an individual may become reinfected after having been cured of previous infection or disease. Although cure of infec-tion or of disease reduces the probability of disease to a very low level, it never eliminates the possibility entirely. - eBook - PDF

- (Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- European Respiratory Society(Publisher)

Eur Respir J ; 36: 1242–1247. N Sester M, et al. (2012). TB in the immunocompromised host. Eur Respir Monogr ; 58: 230–241. N Sester U, et al. (2009). Impaired detec-tion of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis immu-nity in patients using high levels of immunosuppressive drugs. Eur Respir J ; 34: 702–710. N Singh N, et al. (1998). Mycobacterium Tuberculosis infection in solid-organ trans-plant recipients: impact and implications for management. Clin Infect Dis ; 27: 1266–1277. N Solovic I, et al. (2010). The risk of tuber-culosis related to tumour necrosis factor antagonist therapies: a TBNET consensus statement. Eur Respir J ; 36: 1185–1206. ERS Handbook: Respiratory Medicine 247 Latent Tuberculosis Jean-Pierre Zellweger Individuals who are in close contact with a patient with a transmissible form of TB, usually smear-positive pulmonary TB, may inhale droplets containing mycobacteria, which settle in the airways and give rise to a local inflammatory reaction. The risk of infection is related to the concentration of mycobacteria in the air and the duration of contact. Some exposed individuals develop active disease (TB) within a couple of weeks or months, others will control the incipient infection and stay, for a prolonged period (up to years), in a state of equilibrium called ‘latent TB infection’ (LTBI). LTBI and risk of TB Individuals with latent TB have no signs or symptoms of active disease, and only immunological markers of a prior contact with mycobacteria. It is therefore impossible to know whether individuals with LTBI still harbour living mycobacteria. The only gold standard for the infection is the development of the disease, which happens in a minority of exposed individuals. Why and how the infected individuals will develop TB is unknown. Estimates are that , 10% of infected individuals may develop TB, half of them within 2 years after infection, and 90% will never develop the disease. - eBook - PDF

Mycobacterium

Research and Development

- Wellman Ribón(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- IntechOpen(Publisher)

Standardized systems for diagnosis can be useful as tools for screening or for decision‐making in childhood Tuberculosis. Keywords: Tuberculosis, diagnosis, child, adolescents 1. Introduction It is estimated that one‐third of the world population is infected by Mycobacterium Tuberculosis and that each year about nine million people develop the disease, out of which 11% are chil‐ dren. This percentage can be higher in countries with high burden of Tuberculosis (TB). At least one million children are sick with TB every year. In 2015, as many as 210,000 children died from TB, out of which 40,000 were patients coinfected with HIV [1, 2]. It is believed that genetic predisposition influences the resistance of certain individuals who, even in contact with patients with baciliferous TB, are not infected with M. Tuberculosis [3]. In childhood, the distinction between infection and disease is often difficult. Some authors avoid the term latent TB (or latent TB infection) in children, preferring to use the term TB © 2018 The Author(s). Licensee IntechOpen. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. infection. The progression of infection to disease can be subtle and go unnoticed. This dif‐ ficulty becomes more remarkable, often in extrapulmonary TB [ 2, 3]. From a practical point of view, the diagnosis of TB infection occurs when the child is asymp‐ tomatic with normal chest radiography and a reactive TB skin test (TST) or interferon gamma release assays (IGRA). On the other hand, the diagnosis of TB disease or active TB is a chal‐ lenge. It occurs when the child is symptomatic (with symptoms consistent with TB) and chest or other X‐ray is abnormal, compatible with TB.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.