Chemistry

Enzyme Catalyzed Reaction

Enzyme-catalyzed reactions are chemical reactions that are facilitated by enzymes, which are biological catalysts. Enzymes speed up the rate of a reaction by lowering the activation energy required for the reaction to occur. They do this by binding to the reactant molecules and bringing them into close proximity, allowing the reaction to proceed more rapidly.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Enzyme Catalyzed Reaction"

- eBook - PDF

- Ramasamy, K(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Daya Publishing House(Publisher)

1. What is Enzyme Catalysis? -Catalysis is defined as a phenomenon in which the rate of the reaction is altered, and the substance used to accelerate remains unchanged regarding its quantity and chemical properties. The substance used to change the speed of the reaction is termed as a ‘catalyst’. Enzymes are catalysts which are responsible for increasing the rate of reaction. The catalysis in which enzymes act as a catalyst is called enzyme catalysis. 2. Why Enzyme Catalysis is Used in Biomass Conversion? This ebook is exclusively for this university only. Cannot be resold/distributed. ☆ A single molecule of catalysis can transform a million molecules of the reactant per second. Hence it is highly efficient. ☆ Biochemical catalysts are unique in nature i.e. the same catalyst cannot be used in more than one reaction. ☆ The efficiency of any catalyst is maximum at its optimum temperature. The activity declines at either side of the optimum temperature. ☆ Biochemical catalysis is highly dependent upon the pH of the solution. Any catalyst functions best at an optimum pH range of 5-7. ☆ The activity of the enzymes usually increases due to the presence of a co– enzyme or an activator such as Na+, Co2+. The rate of the reaction increases due to the presence of a weak bond which exists between the enzyme and a metal ion. 3. Biochemical Perspective of Enzyme Catalysis In any reaction, the reactant molecules must contain sufficient energy to cross a potential energy barrier, which is called as the activation energy . All molecules possess varying amounts of activation energy depending on their collision but, generally, only a few have sufficient energy for the reaction to occur. The lower the potential energy barrier to reaction, the more reactants possess sufficient energy and, hence, faster the reaction. - Frederick Bettelheim, William Brown, Mary Campbell, Shawn Farrell(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

641 CONTENTS 22.1 Enzymes are Biological Catalysts 22.2 Enzyme Nomenclature 22.3 Enzyme Activity 22.4 Enzyme Mechanisms 22.5 Enzyme Regulation 22.6 Enzymes in Medicine Enzymes 22 22.1 Enzymes are Biological Catalysts The cells in your body are chemical factories. Only a few of the thousands of compounds necessary for the human organism are obtained from the diet. Instead, most of these substances are synthesized within the cells, which means that thousands of chemical reactions take place in your cells every second of your life. Nearly all of these reactions are catalyzed by enzymes , which are large molecules that increase the rates of chemical reactions without themselves undergoing any change. Without enzymes to act as biological catalysts, life as we know it would not be possible. The vast majority of all known enzymes are globular proteins, and we will devote most of our study to protein-based enzymes. However, pro-teins are not the only biological catalysts. Ribozymes are enzymes made of ribonucleic acids. They catalyze the self-cleavage of certain portions of their own molecules and are involved in the reaction that generates pep-tide bonds (Chapter 21). Many biochemists believe that during evolution, RNA catalysts emerged first, with protein enzymes arriving on the scene later. (We will learn more about RNA catalysts in Section 24.4.) Like all catalysts, enzymes do not change the position of equilibrium. That is, enzymes cannot make a reaction take place that would not occur without them. Instead, they increase the reaction rate: they cause reactions © ibreakstock/Shutterstock.com Ribbon diagram of cytochrome c oxidase, the enzyme that directly uses oxygen during respiration. Copyright 2020 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).- eBook - PDF

- A Cavaco-Paulo, G Gubitz(Authors)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- Woodhead Publishing(Publisher)

Some enzymes require small non-protein molecules, known as cofac-tors, in order to function as catalysts. Enzymes differ from chemical catalysts in several important ways: 1. Enzyme-catalysed reactions are at least several orders of magnitude faster than chemically-catalysed reactions. When compared to the 1 corresponding uncatalysed reactions, enzymes typically enhance the rates by 10 6 to 10 13 times. 2. Enzymes have far greater reaction specificity than chemically-catalysed reactions and they rarely form byproducts. 3. Enzymes catalyse reactions under comparatively mild reaction con-ditions, such as temperatures below 100°C, atmospheric pressure and pH around neutral. Conversely, high temperatures and pressures and extremes of pH are often necessary in chemical catalysis. 1.1.1 In this chapter This chapter is concerned mainy with the fundamental aspects of enzymes that determine their properties and catalytic capabilities. It is intended to provide a sound basis for understanding of many of the applied aspects of enzymes considered in subsequent chapters in this text. Given the wealth of fundamental knowledge on enzymes, it is only possible here to provide a perspective on each of the topics. Some of the topics will be considered in more detail, or from a different perspective, later on in the text. Section 1.2 deals with the classification and nomenclature of enzymes. It considers some of the rules that form the basis of a rational system classi-fication and naming enzymes, and provides examples of enzymes in each of the six main classes. Much of the chapter is devoted to protein structure (Section 1.3) because this ultimately defines the properties of enzymes, such as substrate specificity, stability, catalysis and response to physical and chemical factors. - eBook - PDF

- Gorden Hammes(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Of course, a catalyst accelerates the forward and reverse reactions an equal amount since the equilibrium constant cannot be altered by a catalyst. An important principle to remember is that of detailed balance (sometimes called microscopic reversibility). This principle states that if a reaction proceeds through a given pathway (mechanism) in going from reactants to products, then at equilibrium the reaction pathway in going from products to reactants must be exactly opposite that of the forward reaction. This means, of course, that the forward and reverse reactions have identical transition states. This principle also is valid for some nonequilibrium situations, for example, in many steady states. An enzyme is an incredibly efficient catalyst, usually many orders of magnitude more efficient than man-made catalysts for comparable reactions. However, the chemical basis of enzyme catalysis is no different from that found with simple catalysts. Therefore, a brief dis-cussion of the three types of catalysis commonly encountered in chemical reactions is profitable, namely acid-base catalysis, nucleophilic catalysis, and electrophilic catalysis. ACID-BASE CATALYSIS This type of catalysis is involved in virtually every enzymatic reaction. As an example, consider the hydrolysis of esters, a reaction catalyzed by a num-ber of enzymes and by acids and bases. The mechanism proceeds through a transition state of water and ester that has a partial negative charge on the carbonyl oxygen and partial positive charge on the oxygen of the attacking water pa-ll—C. ; OR' / H H The reaction rate can be catalyzed by a base through stabilization of the positive charge by transfer or partial transfer of a water proton to a base. 78 5 Some Chemical Aspects of Enzyme Catalysis Similarly, acid catalysis can be accomplished by transfer or partial transfer of a proton to the carbonyl oxygen. - eBook - PDF

- Douglas S. Clark, Harvey W. Blanch(Authors)

- 1997(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Chapter 1. Enzyme Catalysis Enzymes are one of the essential components of all living systems. These macromo- lecules have a key role in catalyzing the chemical transformations that occur in all cell metabolism. The nature and specificity of their catalytic activity is primarily due to the three-dimensional structure of the folded protein, which is determined by the sequence of the amino acids that make up the enzyme. The activity of globular proteins may be regulated by one or more small molecules, which cause small conformational changes in the protein structure. Catalytic activity may depend on the action of these non-protein components (known as cofactors) associated with the protein. If the cofactor is an organic molecule, it is referred to as a coenzyme. The catalytically inactive enzyme (without cofactor) is termed an apoenzyme; when coenzyme or metal ion is added, the active enzyme is then termed a holoenzyme. Many cofactors are tightly bound to the enzyme and cannot be easily removed; they are then referred to as prosthetic groups. In this chapter we shall examine the nature of enzyme catalysis, first by examining the types of reactions catalyzed and the mechanisms employed by enzymes to effect this catalysis, and then by reviewing the common constitutive rate expressions which describe the kinetics of enzyme action. As we shall see, these can range from simple rate expressions to complex expressions that involve several reactants and account for modification of the enzyme structure. 1.1 Specificity of Enzyme Catalysis Enzymes have been classified into six main types, depending on the nature of the reaction catalyzed. A numbering scheme for enzymes has been developed, in which the main classes are distinguished by the first of four digits. The second and third digits describe the type of reaction catalyzed, and the fourth digit is employed to distinguish between enzymes of the same function on the basis of the actual substrate in the reaction catalyzed. - eBook - PDF

- Edward Bittar(Author)

- 1996(Publication Date)

- Elsevier Science(Publisher)

Chapter 2 How Enzymes Work GARY L. N ELSESTU EN Introduction 25 Free Energy of a Chemical Reaction 26 Step I of Enzyme Catalysis 28 Enzymes Bind Substrates and Align Them for Chemical Reaction 28 Catalysis by an Enzyme Active Site Produces the Phenomenon of 'Saturation Kinetics' 31 Use of Biological Specificity to Create Pharmaceuticals and Other Bioactive Molecules 34 Step 2 of Enzyme Catalysis: Binding is Followed by Chemical Reaction 40 Summary 44 INTRODUCTION Enzymes are responsible for bringing about chemical reactions under the mild conditions that are essential to our existence. In the chemistry lab we often catalyze reactions with heat (refluxing or boiling water temperatures) and acid or base (often 0.1-6.0 molar H § or OH-. However, these conditions are not compatible with life as we know it. While some unusual organisms do exist at high temperatures and in slightly acidic or basic medium, they are the exceptions. Furthermore, even these organisms have adapted by creating ways of keeping the pH inside the cell close to neutral (1 x 10-7M H+). Most organisms, including humans, live at low tempera- Principles of Medical Biology, Volume 4 Cell Chemistry and Physiology: Part I, pages 25-44 Copyright 9 1995 by JAI Press Inc. All rights of reproduction in any form reserved. ISBN: 1-55938-805-6 25 26 GARY L. NELSESTUEN ture (< 37 ~ C) and close to neutral pH. Fluctuations of body temperature by only a few degrees or of pH by a few tenths of a pH unit can create serious conditions for humans. Thus, living organisms require catalysts that can bring about chemical reactions under these mild conditions. In turn, the ways that these catalysts function are responsible for many of the most fundamental properties of living organisms. These properties also help explain the action of many medicines and drugs (as well as herbicides, pesticides, poisons, and all types of bioreactive molecules), and the phenomenon of 'biological specificity'. - eBook - PDF

- Donald Voet, Judith G. Voet(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

We then embark on a detailed examination of the catalytic mechanisms of several of the best characterized enzymes: lysozyme and the serine pro- teases. Their study should lead to an appreciation of the in- tricacies of these remarkably efficient catalysts as well as of the experimental methods used to elucidate their proper- ties. We end with a discussion of how drugs are discovered and tested, a process that depends heavily on the principles of enzymology since many drug targets are enzymes. In do- ing so, we consider how therapeutically effective inhibitors of HIV-1 protease were discovered. 1 CATALYTIC MECHANISMS Catalysis is a process that increases the rate at which a reac- tion approaches equilibrium. Since, as we discussed in Sec- tion 14-1Cb, the rate of a reaction is a function of its free energy of activation (G ‡ ), a catalyst acts by lowering the height of this kinetic barrier; that is, a catalyst stabilizes the transition state with respect to the uncatalyzed reaction. There is, in most cases, nothing unique about enzymatic mechanisms of catalysis in comparison to nonenzymatic mechanisms. What apparently make enzymes such powerful catalysts are two related properties: their specificity of sub- strate binding combined with their optimal arrangement of catalytic groups. An enzyme’s arrangement of binding and catalytic groups is, of course, the product of eons of evolu- tion: Nature has had ample opportunity to fine-tune the performances of most enzymes. The types of catalytic mechanisms that enzymes employ have been classified as: 1. Acid–base catalysis. 2. Covalent catalysis. 3. Metal ion catalysis. 4. Electrostatic catalysis. 5. Proximity and orientation effects. 6. Preferential binding of the transition state complex. In this section, we examine these various phenomena. In doing so we shall frequently refer to the organic model compounds that have been used to characterize these cat- alytic mechanisms. - eBook - PDF

- P Karlson(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Thermodynamically, catalysts lower the necessary energy of activation of the reaction and thus facilitate reaching equilibrium. Enzymes achieve this according to the principle of intermediary catalysis: initially an enzyme-substrate complex, ES, is formed which, in the reaction proper, becomes a complex of enzyme and product, EP. The latter complex then dissociates into enzyme + product, whereby the enzyme is regenerated and free to 4 The change in enthalpy differs from change of heat content (developed or absorbed quantity of heat) only by its sign: AH = —Q p -5 Entropy is a measure of the lack of molecular order. According to Boltzmann, entropy is a measure of the probability of a state: S = k · In W. Disordered states always are more probable than ordered ones. Entropy is expressed in cal/°K or entropy units; the dimension of Τ· AS thus becomes cal, or the dimen-sion of energy. 6 For an introduction to biochemical thermodynamics, see I. M. Klotz, Energy Changes in Biochemical Reactions. Academic Press, New York, 1967. 3. CATALYSTS AND ENZYMES 79 Fig. V -2. Energy of activation and the function of catalysts. associate with another substrate molecule. The energy of activation of each of these steps is considerably smaller than it is for the overall noncatalyzed reaction (cf. Fig. V-2b). The catalyzed reaction therefore proceeds much faster. The net amount of free energy (AG) remains unchanged in the process, and as a result the equilibrium position also remains the same. Catalysis beyond the state of equilibrium, i.e., a shift of equilibrium, is not possible, however. Every reaction, though catalyzed by an enzyme, proceeds only until equilibrium is reached. This same equilibrium would have been reached in the presence of some inorganic catalyst, or even without the aid of a catalyst; the equilibrium is defined alone by the equilibrium constant K. 1 This fundamental law of the action of enzyme must never be forgotten. - eBook - PDF

- P Karlson(Author)

- 1975(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Thermodynamically, catalysts lower the necessary energy of activation of the reaction and thus facilitate reaching equilibrium. Enzymes achieve this according to the principle of intermediary catalysis: initially an enzyme-substrate complex, ES, is formed which, in the reaction proper, becomes a complex of enzyme and product, EP. The latter complex then dissociates into enzyme + product, whereby the enzyme is regenerated and free to 4 The change in enthalpy differs from change of heat content (developed or absorbed quantity of heat) only by its sign: AH = —Q p -5 Entropy is a measure of the lack of molecular order. According to Boltzmann, entropy is a measure of the probability of a state : S = k • In W. Disordered states always are more probable than ordered ones. Entropy is expressed in ca/°K or entropy units ; the dimension of Τ · AS thus becomes cal, or the dimen-sion of energy. 6 For an introduction to biochemical thermodynamics, see I. M. Klotz, Energy Changes in Biochemical Reactions. Academic Press, New York, 1967. F i g . V -2 . Energy of activation and the function of catalysts. associate with another substrate molecule. The energy of activation of each of these steps is considerably smaller than it is for the overall noncatalyzed reaction (cf. Fig. V-2b). The catalyzed reaction therefore proceeds much faster. The net amount of free energy (AG) remains unchanged in the process, and as a result the equilibrium position also remains the same. Catalysis beyond the state of equilibrium, i.e., a shift of equilibrium, is not possible, however. Every reaction, though catalyzed by an enzyme, proceeds only until equilibrium is reached. This same equilibrium would have been reached in the presence of some inorganic catalyst, or even without the aid of a catalyst ; the equilibrium is defined alone by the equilibrium constant K. 1 This fundamental law of the action of enzyme must never be forgotten. - A. Kayode Coker(Author)

- 2001(Publication Date)

- Gulf Professional Publishing(Publisher)

Enzymes operate under mild conditions of temperature and pH. A database of the various types of enzymes and functions can be assessed from the following web site: http://www.expasy.ch/enzyme/. This site also provides information about enzymatic reactions. This chapter solely reviews the kinetics of enzyme reactions, modeling, and simulation of biochemical reactions and scale-up of bioreactors. More comprehensive treatments of biochemical reactions, modeling, and simulation are provided by Bailey and Ollis [2], Bungay [3], Sinclair and Kristiansen [4], Volesky and Votruba [5], and Ingham et al. [6]. KINETICS OF ENZYME-CATALYZED REACTIONS ENZYME CATALYSIS All enzymes are proteins that catalyze many biochemical reactions. They are unbranched polymers of α -amino acids of the general formula 832 Modeling of Chemical Kinetics and Reactor Design The carbon-nitrogen bond linking the carboxyl group of one residue and the α -amino group of the next is called a peptide bond. The basic structure of the enzyme is defined by the sequence of amino acids forming the polymer. There are cases where enzymes utilize prosthetic groups (coenzymes) to aid in their catalytic action. These groups may be complex organic molecules or ions and may be directly involved in the catalysis or alternately act by modifying the enzyme structure. The catalytic action is specific and may be affected by the presence of other substances both as inhibitors and as coenzymes. Most enzymes are named in terms of the reactions they catalyze (see Chapter 1). There are three major types of enzyme reactions, namely: 1. Soluble enzyme—insoluble substrate 2. Insoluble enzyme—soluble substrate 3. Soluble enzyme—soluble substrate The predominant activity in the study of enzymes has been in relation to biological reactions. This is because specific enzymes have both controlled and catalyzed synthetic and degradation reactions in all living cells.- eBook - PDF

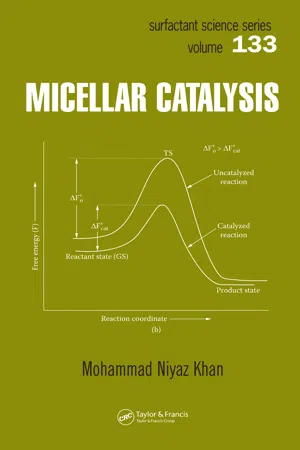

- Mohammad Niyaz Khan(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

89 2 Catalysis in Chemical Reactions: General Theory of Catalysis 2.1 INTRODUCTION Chemical catalysis is an area of tremendous interest because of its occurrence in reactions important to both biochemical, biotechnological, and industrial pro-cesses. The word catalysis ( katalyse ) was coined by Berzelius in 1835. In his words, “ Catalysts are substances, which by their mere presence evoke chemical reactions that would not otherwise take place.” In a 14th-century Arabian manuscript, Al Alfani described the “xerion, alaksir, noble stone, magisterium, that heals the sick and turns base metals into gold, without in itself undergoing the least change.” 1 A small amount of catalyst suffices to bring about great changes without itself being consumed. Wilhelm Ostwald was the first to emphasize the effects of a catalyst on the rate of a chemical reaction and his famous definition of catalyst was: “a catalyst is a substance that changes the velocity of a chemical reaction without itself appearing in the end products.” Based on the essence of the first law of thermo-dynamics, Ostwald showed that a catalyst cannot change the equilibrium. Because equilibrium K = k f /k b (where k f and k b represent rate constants for forward and backward reactions in an equilibrium chemical process, respectively), the catalyst must change both k f and k b in the same proportion and in the same direction. This statement, although true in its essence, has been vaguely interpreted in some popular books of physical chemistry.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.