Biological Sciences

Enzymes

Enzymes are biological molecules that act as catalysts, speeding up chemical reactions within living organisms. They are typically proteins that bind to specific substrates and facilitate the conversion of these substrates into products. Enzymes are essential for various physiological processes, such as digestion, metabolism, and cellular signaling, and they play a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis within the body.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Enzymes"

- No longer available |Learn more

- Gustavo Blanco, Antonio Blanco(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Countless chemical reactions take place at a given time in every living being. Many of them transform exogenous substances, which come with the diet, to obtain energy and the basic materials that will be used for the synthesis of endogenous molecules.Biochemical transformations are performed at a remarkable fast rate and with great efficiency. To reproduce them in the laboratory, these reactions would need extreme changes in temperature, pH, or pressure to take place; these changes are not compatible with cell survival. Under normal physiological conditions (37°C for warm-blooded organisms, pH near neutrality, and constant pressure), most of the reactions would proceed very slowly or may not occur at all. It is the presence of catalysts that allow chemical reactions in living beings to occur with great speed and under the mild conditions that are compatible with life.Enzymes are biological catalysts

A catalyst is an agent capable of accelerating a chemical reaction without being part of the final products or being consumed in the process. In biological media, macromolecules called Enzymes act as catalysts.As any catalyst, Enzymes work by lowering the reaction activation energy (A e ) (see p. 152). Enzymes are more effective than most inorganic catalysts; moreover, Enzymes show a greater specificity of effect. Usually inorganic catalysts function by accelerating a variety of chemical reactions, whereas Enzymes catalyze only a specific chemical reaction. Some Enzymes act on different substances, but generally, these are compounds with similar structural characteristics and the catalyzed reaction is always of the same type.The substances that are modified by Enzymes are called substrates .The specificity of Enzymes allows them to have high selectivity to distinguish among different substances and even between optical isomers of a compound. For example, glucokinase, an enzyme that catalyzes d -glucose phosphorylation, does not act on l - eBook - PDF

- A Cavaco-Paulo, G Gubitz(Authors)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- Woodhead Publishing(Publisher)

1 Enzymes RICHARD O. JENKINS De Montfort University, UK 1.1 Introduction Enzymes are biological catalysts that mediate virtually all of the biochem-ical reactions that constitute metabolism in living systems. They accelerate the rate of chemical reaction without themselves undergoing any per-manent chemical change, i.e. they are true catalysts. The term ‘enzyme’ was first used by Kühne in 1878, even though Berzelius had published a theory of chemical catalysis some 40 years before this date, and comes from the Greek enzumé meaning ‘in ( en ) yeast ( zumé )’. In 1897, Eduard Büchner reported extraction of functional Enzymes from cells. He showed that a cell-free yeast extract could produce ethanol from glucose, a biochemical pathway now known to involve 11 enzyme-catalysed steps. It was not until 1926, however, that the first enzyme (urease from Jack-bean) was purified and crystallised by James Sumner of Cornell University, who was awarded the 1947 Nobel Prize. The prize was shared with John Northrop and Wendell Stanley of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, who had devised a complex precipitation procedure for isolating pepsin. The procedure of Northrop and Stanley has been used to crystallise several Enzymes. Subsequent work on purified Enzymes, by many researchers, has provided an understanding of the structure and properties of Enzymes. All known Enzymes are proteins. They therefore consist of one or more polypeptide chains and display properties that are typical of proteins. As considered later in this chapter, the influence of many chemical and physi-cal parameters (such as salt concentration, temperature and pH) on the rate of enzyme catalysis can be explained by their influence on protein struc-ture. Some Enzymes require small non-protein molecules, known as cofac-tors, in order to function as catalysts. Enzymes differ from chemical catalysts in several important ways: 1. - eBook - PDF

- Khushboo Chaudhary, Pankaj Kumar Saraswat(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Delve Publishing(Publisher)

ENZYMOLOGY CHAPTER2 12. INTRODUCTION: REVIEW OF A BRIEF HISTORY, Enzymes AS BIOLOGICAL CATALYSTS, CLASSIFICATION, NOMENCLATURE, PROXIMITY AND ORIENTATION, COVALENT CATALYSIS, ACID-BASE CATALYSIS. Introduction It is the most remarkable and highly specialized protein. Catalyze hundreds of stepwise reactions in biological systems. Regulate many different metabolic activities necessary to sustain life. Living systems use catalysts called Enzymes to increase the rate of chemical reactions. The study of Enzymes has immense practical importance. In medical science: to know the epidemiology, to diagnose, and to treat diseases (inheritable genetic disorders). • In chemical industries • In food processing • In agriculture • In everyday activities in the home (food preparation, cleaning, beauty care ,etc.) Basic Biology 94 Nomenclature of Enzymology The International Enzyme Commission (EC) has recommended a systematic nomenclature for Enzymes. This commission assigns names and numbers to Enzymes according to the reaction they catalyze. An example of a systematic enzyme name is EC 3.5.1.5 urea aminohydrolases for the enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea. The name of an enzyme frequently provides a clue to its function. In some cases, an enzyme is named by incorporating the suffix -ase into the name of its substrate, e.g., pyruvate decarboxylases catalyzes the removal of a CO 2 group from pyruvate. Certain protein cutting digestive Enzymes are an exception to this general rule of enzyme nomenclature, e.g., pepsin, trypsin, chymotrypsin and thrombin. Isozyme:Within an organism, more than one enzyme may catalyze a given reaction. Multiple Enzymes catalyzing the same reaction is called isozymes (Scribd, slideshare, molecular-plant-biotechnology, slideplayer, documents, docplayer, bmb.psu, powershow, bioscience, docslide, msluay, scienceprofonlue, biotechuniverse.blogspot). - eBook - PDF

- Edward Bittar(Author)

- 1996(Publication Date)

- Elsevier Science(Publisher)

In turn, the ways that these catalysts function are responsible for many of the most fundamental properties of living organisms. These properties also help explain the action of many medicines and drugs (as well as herbicides, pesticides, poisons, and all types of bioreactive molecules), and the phenomenon of 'biological specificity'. It should be stressed that this chapter takes the minimalist attitude about Enzymes themselves. That is, it presents the smallest amount of enzymology needed to understand some basic features of biology and medicine. This presentation will briefly outline some of the mechanisms of enzyme catalysis and will spend most of the time describing the ramifications of these mechanisms for more overt biological properties. Enzyme behavior provides a foundation for understanding the mode of action of many of the chemicals used in medicine. - eBook - PDF

- J. M. M. Brown, G. G. Járos(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Butterworth-Heinemann(Publisher)

CHAPTER 8 Enzymatic and Genetic Control of Reactions The chemical reactions which take place in living systems proceed at an amazingly fast rate when compared to the rate at which the same reactions would take place in a test tube under experimental conditions. The acceleration of these reactions in biological systems is achieved by Enzymes. Enzymes are catalysts, i.e., they can accelerate a reaction without themselves being permanently altered during the process. As a result of their catalyzing ability Enzymes have two very important functions. 1. Enzymes localize reactions. A chemical reaction will generally pro-ceed on its own anywhere at its own slow rate provided that the reac-tants are freely available and that other essential conditions are met. The same reaction will, however, proceed at a faster and therefore more useful rate, in those parts of the body, or those particular cells or tissues where it is actually required for physiological purposes and where the catalyzing enzyme is actually present. The presence of large amounts of an enzyme in a certain tissue determines therefore to a large extent, where a particular type of reaction will take place in the body. This localization of function is even more evident within cells, where certain types of reactions are confined to the mitochon-dria, others to the cell sap and yet others to the nucleus and so on. 2. Enzymes determine the rate of reactions. The extent to which reac-tions are accelerated depends on the amount of Enzymes that will have to combine, even though temporarily, with the reactants or substrates as they are called in this case. Since each type of chemical reaction in the tissues of the body is determined by the localization and availability of Enzymes, the total arrangements of chemical reactions in the body to form an integrated biochemical whole will be determined by these factors as well. - eBook - PDF

- Raj Lad(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

4 Introduction to Enzymes and Their Applications in Personal Care James T. Kellis, Jr. and Raj Lad Genencor International, a Danisco Company, Palo Alto, California, U.S.A. BASIC PRINCIPLES Introduction Enzymes are biological catalysts. They are found both inside and outside of cells, and these fascinating molecules dramatically accelerate chemical reactions, often by many orders of magnitude compared to the uncatalyzed reaction. Enzymes are protein molecules and are very complex. A protein consists of a linear chain of hundreds of amino acid building blocks, which are produced in the cell, like beads on a string. Each chain of amino acids folds up into a very specific compact form, dictated by its linear amino acid sequence. Proteins are composed of 20 different types of amino acids, and it is the chemical properties of these amino acids and the interactions between them that dictate the particular compact form the amino acid sequence will adopt. In this manner, the linear sequence of the amino acid chain dictates the three-dimensional shape of a protein and consequently its function. The three-dimensional structure of a protein determines the location of crucial amino acids and puts them in position to carry out the function of the protein, such as catalysis of a chemical reaction or recognition and binding to such molecules as DNA, proteins, hormones, meta-bolites, or drugs. Some Enzymes are composed of multiple protein molecules that are associated noncovalently in a specific arrangement. The linear sequence of amino acids in a given protein is determined by the linear DNA sequence of the gene representing the protein. Protein synthesis 87 occurs through an intermediary molecule, messenger RNA, which is “transcribed” from the DNA sequence. At the ribosome, the messenger RNA sequence is “trans-lated” into the corresponding amino acid sequence. - eBook - PDF

Biochemistry

An Integrative Approach

- John T. Tansey(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Categorize these reactions based on the six types of reactions found in section 4.1.2. 4.1 Summary • Enzymes are protein catalysts that increase rates of reaction by lowering activation energy. • Enzymes are often globular proteins that may be monomeric or multimeric. • Substrates (the reactants) are converted to products in the active site of the enzyme, a surface cleft that specifically binds the substrate. • The active site binds substrate like a key in a lock or a hand in a glove. The binding is specific and tight, with solvent often being excluded. • Enzymes can be categorized based on the type of reaction they catalyze. • Enzymes do not alter equilibrium, but they do allow systems to achieve equilibrium more quickly than would be the case in the absence of a catalyst. 4.1 Concept Check • Describe what generally happens in an enzymatically catalyzed reaction. • Describe the interactions of substrate and enzyme using the proper biochemical terminology. • Describe the two models (lock and key and induced fit) that are used to describe these interactions. • Use a simple thermodynamic argument to describe why Enzymes increase the rate of a reaction. 108 CHAPTER 4 Proteins II 4.2 Enzymes Increase Reaction Rate Rates of enzymatically catalyzed reactions can be derived from rates of chemical reactions and are powerful tools for describing reactions. 4.2.1 A review of chemical rates The rate of a chemical reaction is defined as the change in concentration of a reactant or product over time. Using square brackets to denote molar concentrations and the notation of calculus gives: [ ] or [ ] d R dt d P dt (4.1) If this is the simplest reaction, where a single molecule of reactant is being changed into product, then the loss of reactant will equal the gain in product: d R dt d P dt - = [ ] [ ] (4.2) In the simplest chemical reaction, such as an isomerization, a single molecule of A reacts to form a molecule of B. - eBook - PDF

- P Karlson(Author)

- 1975(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

C H A P T E R Enzymes and Biocatalysis 1. Chemical Nature of Enzymes The Enzymes are a very important group of proteins. All the chemical reactions in the organism (i.e., metabolism) are made possible only through the actions of the catalysts that we call Enzymes. The substance transformed by an enzyme is termed substrate. Although the German literature still uses both the terms ferment and enzyme, only the latter is used in the English language, and fermentation is restricted to describing bacterial actions. The use of the word enzyme, proposed by Kühne in 1878, for soluble ferments avoids the historical controversy concerning formed ferments (yeast and other microorganisms, i.e., intact organisms) and unformed ferments (pepsin, trypsin, saccharase). After Buchner's epoch-making discovery that alcoholic fermenta-tion is indeed possible outside the living cell, the concept of formed ferment was dropped, and the designa-tions ferment and enzyme became synonymous. Chemically every enzyme known so far is a protein. About one hundred Enzymes have been prepared in pure and crystalline form by the methods of protein chemistry ; the first of these was urease (Sumner, 1926). Ribonuclease, trypsin, chymotrypsin, and lysozyme are a few of the Enzymes whose structure, i.e., amino acid sequence, have been analyzed completely ; the sequences of other Enzymes are only partially known. The assumption is that a certain sequence of amino acids at and around the active site of the enzyme is responsible for the catalytic effect. This theory is supported by the observation that part of the molecule may be split off some Enzymes without loss of activity. Denaturation abolishes catalytic activity, of course, without changing the sequence of amino acids. Many Enzymes are complex proteins; they consist of a protein component and a prosthetic group. Some Enzymes in their active form bind the prosthetic group in 74 - eBook - PDF

- N.A.M. Eskin(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

A particular enzyme may catalyze a relatively small number of reactions, or, as in the great majority of cases, one reaction only. By inference this implies that a cell must contain a vast number of Enzymes, set in some kind of balanced cellular organization, in order to carry out all its vital metabolic activities. III. Properties of Enzymes 113 1. Stereochemical Specificity Many compounds occurring in biological material have two possible stereo-isomeric forms, but normally only one of these forms is found in nature. For example, nearly all the monosaccharides occur as the D-form, and all the amino acids as the L-form. Many Enzymes show a strong preference for one member of a pair of stereoisomers. For example, the reaction catalyzed by lactic de-hydrogenase can be shown thus: NAD + CH 3 COOH Pyruvic acid This enzyme has no effect on D(—)-lactic acid. A second example involves cis-trans geometrical isomerism. Succinic dehydrogenase converts succinic acid into fumaric acid, which has a trans configuration, but not into the corre-sponding eis compound, maleic acid: 2H HOOCCH — + ii CHCOOH Fumaric acid (trans) 2. Low Specificity The enzyme is specific only toward the linkage which is to be split. For ex-ample, lipase hydrolytically splits the ester linkage between the acid and the alcohol in almost any wholly organic ester, for example, triglyceride or ethyl butyrate. 3. Group Specificity In this instance the enzyme acts upon a substrate in which there is a specific chemical linkage, and a specific group on one side of the linkage. For example, trypsin, an endopeptidase, cleaves only peptide linkages which involve the carboxyl group of lysine or arginine. 4. Absolute Specificity This is the most abundant and exclusive type of specificity. The enzyme is specific for one substrate and one reaction only, for example, urease, and malt-maltase which hydrolyzes maltose to form two molecules of -D-glucose. - eBook - PDF

- P Karlson(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

C H A P T E R Enzymes and Biocatalysis 1. Chemical Nature of Enzymes The Enzymes are a very important group of proteins. All the chemical reactions in the organism (i.e., metabolism) are made possible only through the actions of the catalysts that we call Enzymes The substance transformed by an enzyme is termed substrate. Although the German literature still uses both the terms ferment and enzyme, only the latter is used in the English language, and fermentation is restricted to describing bacterial actions. The use of the word enzyme, proposed by Kuhne in 1878, for soluble ferments avoids the historical controversy concerning formed ferments (yeast and other microorganisms, i.e., intact organisms) and unformed ferments (pepsin, trypsin, saccharase). After Buchner's epoch-making discovery that alcoholic fermenta-tion is indeed possible outside the living cell, the concept of formed ferment was dropped, and the designa-tions ferment and enzyme became synonymous. Chemically every enzyme known so far is a protein. About one hundred Enzymes have been prepared in pure and crystalline form by the methods of protein chemistry; the first of these was urease (Sumner, 1926). Ribonuclease, trypsin, chymotrypsin, and lysozyme are a few of the Enzymes whose structure, i.e., amino acid sequence, have been analyzed completely; the sequences of other Enzymes are only partially known. The assumption is that a certain sequence of amino acids at and around the active site of the enzyme is responsible for the catalytic effect. This theory is supported by the observation that part of the molecule may be split off some Enzymes without loss of activity. Denaturation abolishes catalytic activity, of course, without changing the sequence of amino acids. Many Enzymes are complex proteins; they consist of a protein component and a prosthetic group. Some Enzymes in their active form bind the prosthetic group in 74 ν 2. CHEMICAL EQUILIBRIA AND CHEMICAL ENERGETICS 75 a reversible manner. - eBook - PDF

Biochemistry

The Chemical Reactions Of Living Cells

- David Metzler(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Most of the machinery of cells is made of en-zymes. Hundreds of them have been extracted from living cells, purified and crystallized. Many others are recognized only by their catalytic action and have not yet been isolated in pure form. While most of the known Enzymes are soluble globular proteins, the structural proteins of the cell may also exhibit catalysis. Thus, actin and myosin together catalyze the hydrolysis of ATP (Chapter 4, Section F). (However, we do not un-derstand how this enzymatic reaction is coupled to movement of the muscle filaments.) A vast literature documents the properties of Enzymes as catalysts and as proteins. Because of this the beginner is apt to lose sight of some simple and fundamental questions: How did we learn that the cell is crammed with Enzymes? How do we recognize that a protein is an en-zyme? Part of the answer to both questions is that Enzymes are recognized only by their ability to catalyze chemical reactions. Thus, an everyday operation for most biochemists is the measure-ment of catalytic activity of Enzymes. Only by measuring rates of catalysis carefully and quanti-tatively has it been possible to isolate and purify these remarkable molecules. The quantitative study of catalysis by Enzymes Enzymes: The Protein Catalysts of Cells (enzyme kinetics) is a highly developed mathemat-ical branch of science that is of utmost practical importance to the biochemist. Study of kinetics is our most important means of learning about the mechanisms of catalysis at the active sites of en-zymes. Kinetic studies are used to measure the af-finity and the specificity of binding of substrates and of inhibitors to Enzymes, to establish max-imum rates of catalysis by specific Enzymes, and in many other ways. The following section contains a brief summary of basic concepts together with some practical tips. - eBook - PDF

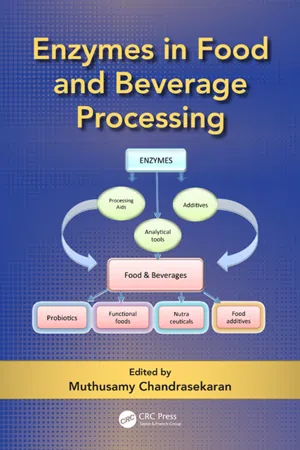

- Muthusamy Chandrasekaran(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

• In optical specificity , the enzyme is specific not only to the substrate but also to its optical con-figuration, for example, L-amino acid oxidases act on L-amino acids, and β -glycosidase acts on β -glycosidic bonds in cellulose. • Enzymes with dual specificity have the ability to act on two substrates, for example, xanthine oxidase converts hypoxanthine to xanthine and xanthine to uric acid. 1.7 Bioenergetics and Enzyme Catalysis 1.7.1 Concepts of Bioenergetics Bioenergetics deals with changes in energy and in comparable factors, even as a biochemical process takes place, but not with the mechanism of the reactions or the speed thereof. The first law of thermodynamics states that energy can neither be created nor destroyed but can be converted into many other forms of energy or be used to do work. The second law of thermodynamics deals with entropy or degree of disorder. It states that entropy in the universe is perpetually increasing. It does not distinguish between different systems, 14 Enzymes in Food and Beverage Processing be it any living cell, a locomotive engine, or any chemical reaction. However, from a state of low entropy maintained by the consumption of chemical energy (in the form of food) in other organisms to light energy by photosynthesis in plants, life ultimately approaches thermody-namic equilibrium via death and decay. Living systems operating at constant temperatures and pressures cannot use heat energy to perform work. Under these circumstances, the concept of two energy forms has been put forth: one that can be used to perform work, also called free energy , and another that cannot. 1.7.2 Enthalpy, Entropy, and Free Energy Under thermodynamic considerations, a system that allows exchange of energy with its surroundings but not with matter is a closed system .

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.