Computer Science

Repetitive Strain Injury

Repetitive Strain Injury (RSI) refers to a condition caused by repetitive movements and overuse of muscles, tendons, and nerves. In the context of computer science, RSI commonly affects individuals who spend long hours typing or using a mouse. Symptoms may include pain, stiffness, and numbness in the affected areas. Prevention and treatment often involve ergonomic adjustments, regular breaks, and exercises to reduce strain.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

5 Key excerpts on "Repetitive Strain Injury"

- eBook - PDF

Diamonds Are Forever, Computers Are Not: Economic And Strategic Management In Computing Markets

Economic and Strategic Management in Computing Markets

- Shane Greenstein(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- ICP(Publisher)

Part II Observations, Fleeting and Otherwise This page intentionally left blank 37 7 Repetitive Stress Injuries My keyboard manufacturer places a warning against improper use on the underside of my keyboard. The warning begins “Continuous use of a key-board may cause Repetitive Stress Injuries or related injuries.” Later it says, “If you feel any aching, numbing or tingling in your arms, wrists or hands, consult a qualified health professional.” This is serious stuff. The potential health problems can be painful, worrisome, and costly. Carpal tunnel syndrome, the repetitive stress injury receiving the most publicity, can cripple. Other related ailments should get immediate medical attention. By most accounts, the most vulnerable workers include journalists, typists, and computer programmers. Most observers blame the recent epidemic of RSIs on the diffusion of PCs into the workplace. Just below the surface of these medical issues lie confusion and some tragedy. Serious injuries go untreated as the medical system bounces sufferers around. Some of the afflicted cannot raise the money to pay for care. Large employers of typists and programmers fear major medical expenses. Manufacturers feel the need to place bland warnings on their equipment. Though RSIs connect all these events, they also have another thing in common. The confusion and uncertainty accompanying RSIs stems from the peculiar way insurance works in our market-oriented society. This may take some explaining. Source: © 2003 IEEE. Reprinted, with permission, from IEEE Micro, October 1996. The basics of insurance and RSIs To start, we observe that human beings are biologically geared toward han-dling a wide variety of muscular tasks, not the same one all day. For this simple reason, RSIs have been around ever since Western countries indus-trialized (and probably before that too). In the past, RSIs afflicted workers on assembly lines and violinists on the road to Carnegie Hall. - eBook - PDF

Ergonomics Process Management

A Blueprint for Quality and Compliance

- James P. Kohn(Author)

- 1998(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

The inability to recover from RSIs can be a function of employees’ personal predisposition, their jobs, their required activity, or a combination of these factors (Powell, 1995). From a personal perspective, nonwork factors such as age, gender, obesity, medical history, and even the use of medication can increase the risk of developing RSIs. In addition, hobbies or work activities that are repetitive, require excessive grip or pinch forces, or involve the use of vibrating tools or awkward motions and postures also increase the risk. Unlike most injuries, RSIs are 24-hour problems that typically cannot be traced back to a specific cause or a single incident. Repetitive stress injuries do not result strictly from work activities or hobbies. Rather, they can result from a combination of work activity and personal factors. Employees must recognize and acknowledge the fact that everything they do can impact their health. Human bodies do not differentiate between activities associated with tasks that are paid and those associated with entertainment or enjoyment. Chronic reactions with delayed manifestation of symptoms can make it difficult to determine if workers had pre-existing conditions. This can create difficulty for health-care providers in determining if diagnosed problems were job related. As a result, arguments and possible litigation often occur to determine whether or not some claims are work related (Dimmitt, 1995). So much has been studied and written on this topic that a comprehensive examination of CTDs or RSIs would require a series of large handbooks. In this chapter we will take a superficial look at RSIs or CTDs. The goal is to provide the safety professional with a fundamental knowledge of this subject. Workplace signs and medical symptoms will be discussed, as well as strategies for the control of repetitive motion problems that should be considered when implementing an Ergo-nomics management process. - eBook - PDF

Injury

The Politics of Product Design and Safety Law in the United States

- Lochlann Jain(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

356 With rising industrialization, repetitive strain injuries erupted in major proportions at the end of the nineteenth century with writers’ cramp. Symptoms of writers’ cramp, also known as scriveners’ palsy, reported from 1820 and increasingly through the 1880s, included symptoms similar to those of computer-related RSIs—intense pain, prickling, stiffness, eventually anesthesia and paralysis. The condition overwhelmingly affected males of prime working age. Reasons given for this outbreak were the prevalence of poor penmanship, the intro-duction of the steel nib, and the rise of a clerical class. 357 One contempo-rary commentator blamed “the increased speed and recklessness with which [the pen] is driven in our modern struggle for existence.” 358 One of the recommended treatments, ironically, was switching from hand-writing to typewriting. Thus, injuries of the hand and wrist resulting from repetitive activi-ties—particularly those based in written communication—were well-known by the time of the introduction of the typewriter, and more so C H A P T E R 3 96 with the introduction of the computer keyboard. In fact, judging by the history and severity of hand injuries and the corresponding impor-tance of the hand to human functioning, the factors of causation of the RSI epidemic of the 1990s would have been mind-bogglingly predict-able for anyone who cared to look at the historical record. It is precisely this record that I will offer here. In this genealogy of the lawsuits, I juxtapose histories of the type-writer, women’s entry into the workforce, and twentieth-century inju-ries of the hand and wrist to offer a social ergonomics through which women as bodies with particular social positions and typing as a prac-tice uneasily circulated in fields of social relations. - eBook - PDF

Occupational Ergonomics

Theory and Applications, Second Edition

- Amit Bhattacharya, James D. McGlothlin(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Despite all these changes, musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), also referred to as cumu-lative trauma disorders (CTDs) or repetitive strain injuries (RSIs), are unfortunately still with us. The main areas of the body involved with computer-associated injuries include the upper extremity, the shoulder and neck, as well as the low back. In addition to MSDs, computer users often encounter eyestrain. The variety of office equipment including chairs, mice, keyboards, and monitors has also expanded, and the Internet and networking groups have made access to this infor-mation available to almost everyone. Some of the products touted as ergonomic may not be well designed. Even well-designed products do not fit every situation. The interaction between computer and user is complex. Changing one variable affects all the other rela-tionships. For example, changing the height of the seat pan on the chair affects how the upper extremity interacts with the keyboard and mouse, and how the head and eyes are positioned to view the display screen. 15.2 METHODS 15.2.1 Risk Factors Ergonomic assessments are done in a variety of ways. Dr. Thomas J. Armstrong and his associates (Silverstein et al., 1987; Armstrong, 1988) at the University of Michigan identi-fied occupational risk factors associated with the development of MSDs in their studies of the meat-processing plants of the Midwestern United States (Armstrong et al., 1982). These occupational risk factors include repetition, force, sustained or awkward postures, contact stress, vibration, and cold. The factors relevant to office work are the first four. 15.6 Implementation of Office Ergonomics Programs 437 15.6.1 Cost 437 15.6.2 Purchasing 438 15.6.3 Education and Training 438 15.7 Summary and Conclusion 439 15.7.1 Chair Buying Guidelines 439 Problems of Office Ergonomics 440 References 443 - eBook - PDF

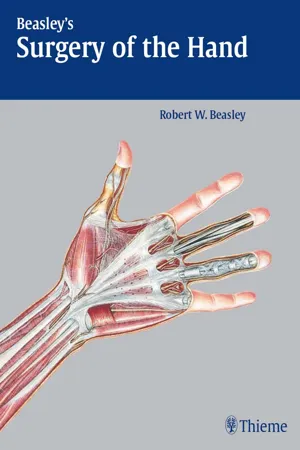

- Robert W. Beasley(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Thieme(Publisher)

24 Chronic Connective Tissue Inflammatory Disorders Attributed to Repetitive Motion Cumulative trauma disorders (CTDs) and repetitive stress injury (RSI) have replaced back injuries as the largest on-the-job medical worker’s compensation to industry expense. I submit that with our current level of knowledge, or level of ignorance, the terms used in referring to this group of problems are neither inclusive nor descriptive. Others have recognized this as well. For example, in Australia the rather clumsy term cervical brachial pain syndrome has come into common usage. There is scant evidence that light, repetitive activities are traumatic to the neck, shoulders, and upper limbs, and certainly there is no evidence that usage causes tissue injury, as Hadler (1997) has emphasized. In fact, hands tend to develop disorders following disuse or prolonged immobilization, rather than from overuse. The nature of these problems or even their existence as physical pathology as opposed to occupational neurosis, is controversial. Arguments so far have been based not on scientific data (of which there are little or none), but on unproven assumptions and epidemiological studies, perpetuated by admin-istrative rulings and legal claims. I basically agree with Mackinnon (1997) that the problems are not purely neuroses. If one follows most cases long enough, purely subjective complaints usually are progressively accompanied by develop-ment of objective evidence of pathology. As will be discussed later, there is increasing evidence that the disorder is not a disturbance of the prime mover muscles but a nutritional disturbance of the stabilizer and antagonist muscle groups. Thus, a term such as sustained activities disorder (SAD) I suggest is more appropriate for these types of complaints. Aches and pains are a part of living, yet the perception of their causes varies enormously (see Chapter 23).

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.