Andrew Johnson Reconstruction Plan

What Was the Andrew Johnson Reconstruction Plan?

The Andrew Johnson Reconstruction Plan, often called "restoration," was a post-Civil War policy designed to quickly reintegrate Southern states into the Union (Donna L. Dickerson et al., 2003). Following Abraham Lincoln's assassination in 1865, Johnson implemented a lenient strategy while Congress was in recess to preempt legislative interference (Jeffrey K. Tulis et al., 2018). His approach was based on the belief that Southern states had never legally left the Union, making formal "reconstruction" unnecessary in his view (Dan Monroe et al., 2005).

Key Provisions of the Andrew Johnson Reconstruction Plan

Under the Andrew Johnson Reconstruction Plan, Southern states were required to nullify secession, abolish slavery, and ratify the Thirteenth Amendment (Edgar J. McManus et al., 2014). He issued an Amnesty Proclamation restoring property rights to most Confederates who took a loyalty oath, though high-ranking officials and wealthy individuals with over $20,000 in property required direct presidential pardons (Edgar J. McManus et al., 2013). Despite his initial rhetoric, Johnson liberally granted over 13,000 pardons, allowing former Confederate leaders to regain political power (Paul Boyer et al., 2017).

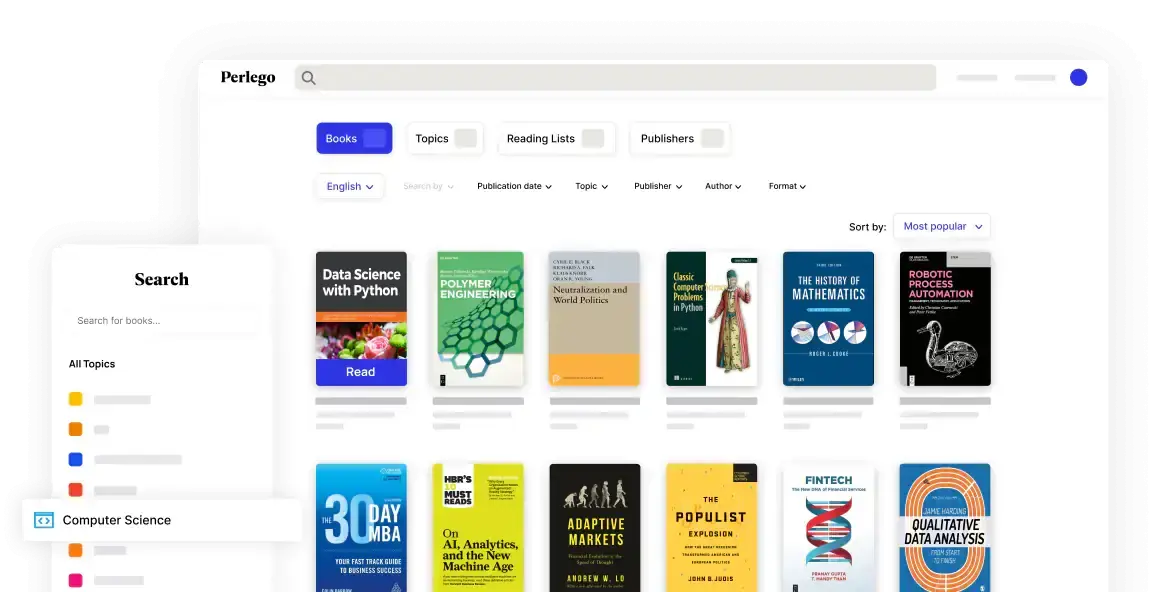

Your digital library for Andrew Johnson Reconstruction Plan and History

Access a world of academic knowledge with tools designed to simplify your study and research.- Unlimited reading from 1.4M+ books

- Browse through 900+ topics and subtopics

- Read anywhere with the Perlego app

Impact and Conflict with Radical Republicans

The Andrew Johnson Reconstruction Plan faced intense opposition from Radical Republicans, who sought a harsher readmission process and protections for freedmen (Jane Kamensky et al., 2017). While Johnson’s policy allowed states to reorganize themselves, it resulted in the passage of "black codes" that severely restricted the rights of formerly enslaved people (Paul Boyer et al., 2017). This leniency, combined with Johnson's refusal to grant African American suffrage, led to a bitter struggle for control over the Reconstruction process (Dan Monroe et al., 2005).

Historical Significance of the Andrew Johnson Reconstruction Plan

The failure of the Andrew Johnson Reconstruction Plan paved the way for "Congressional Reconstruction," as the Republican-controlled Congress seized control to impose more stringent requirements on the South (Jane Kamensky et al., 2017). Johnson's "restoration" ultimately allowed the Southern status quo to persist, facilitating the rise of white supremacy and sharecropping (John Murrin et al., 2013). His contentious leadership and stubborn adherence to states' rights made him a "misfit" president during one of America's most critical eras (David Kennedy et al., 2019).